The man who created London – and other urban master planners

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge

When TS Eliot wrote those lines in the early 1920s London was a polluted, overcrowded metropolis blighted by heavy industry, poverty and slums. Forty years later city workers’ spacious new homes in airy, leafy suburbs and new towns were memorialised by John Betjeman. He wrote in 1962:

One can’t be sure where London ends,

New towns have filled the fields of root

Where father and his business friends

Drove in the Landaulette to shoot;

This sharp contrast reflects a historic turning point in London’s history.

The move to suburbs – including Betjeman’s fabled “Metro-Land” – was already under way by the time Eliot published “The Waste Land” in 1922. Two world wars and Britain’s decline as a seafaring empire turned the trickle of inhabitants leaving the city into a flood.

By the time Betjeman wrote his lines, what had begun as a profitmaking attempt by a handful of developers had turned into government policy – a mass movement of people out of London.

The man who changed Eliot’s brown-fogged crowds into Betjeman’s suburbanites was Patrick Abercrombie. While the second world war still raged, he was commissioned to create a vision for London’s post-victory future, and drawing on a series of preceding commissions, he came up with the city’s first and only comprehensive regional plan.

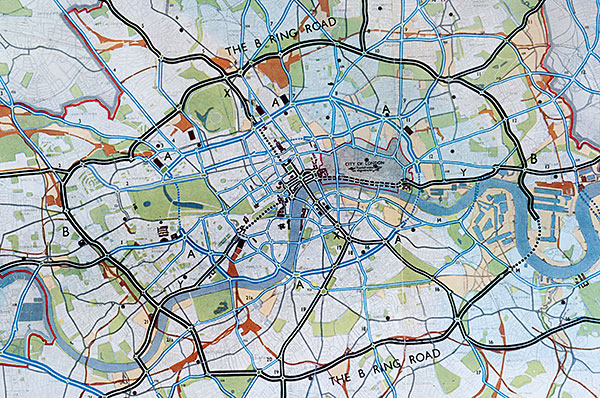

Published 70 years ago, the Greater London Plan contained most major physical developments that the capital has since seen. New towns, the M25 orbital motorway, airports Heathrow and Gatwick and the greenbelt of protected countryside which surrounds the city – all were set out by Abercrombie.

Renowned urbanist Sir Peter Hall, who died this summer, described Abercrombie earlier this year as one of the last powerful and visionary architect-planners. Yet, Sir Peter argued, the ideas behind Abercrombie’s plan – transport, open spaces and the blending of industry and housing – are still relevant today. More than half of the world’s population now lives in cities and that proportion is set to rise to two-thirds by 2050.

“With the pace of urbanisation around the world, there are many examples of unplanned urban conurbations – ranging from places that are fairly successful and become proper cities, to sprawling, terribly unhealthy informal communities,” says Patrick Philips, chief executive of the Urban Land Institute, a US-based think-tank.

In the decades since Abercrombie’s work was published, few people have attempted to emulate the scale of his ambition. Boris Johnson, the current mayor of London, has tried, with ideas such as underground motorways and a 35-year infrastructure spending plan, although his bid to relocate Heathrow airport to the Thames estuary was recently rejected. Launching the infrastructure plan this summer, Johnson set out his differences with Abercrombie, saying: “The population of London went down by about 2m and the city went through one of its gloomiest and most depressing phases in the last 200 years. It wasn’t the right approach.” The economic success of the new towns harmed London itself, Johnson argued.

His remarks reflect a backlash against Abercrombie that has been building for several decades. London’s population bottomed out at 6.4m in 1991 and has been growing steadily since. It is set to hit a record high early next year. To house all these people, city planning has shifted emphasis from depopulation to densification.

Deputy mayor Sir Edward Lister says: “The bit [of the Abercrombie plan] that none of us agree with now is the idea that big cities are bad and his attempts to move people out of London. It was all about urban clearance. London has built only around 25,000 homes a year since the 1950s, and it is only now that we’re starting to ramp up to serious housebuilding levels again.”

So does London need a new Abercrombie plan? “London is Europe’s first megacity,” says Andrew Jones of planning consultancy Aecom. “We need to go back to the scale and ambition of Abercrombie’s plan. We need to see London as a 20m-people city and plan it in that way. That doesn’t mean building over the countryside but it does mean connecting up the London region.”

Yet while London still needs long-term planning, perhaps it would not want a new Abercrombie, says Rob Krzyszowski from Britain’s Royal Institute for Town Planning. “One of the criticisms of planning in the past was that there wasn’t enough public involvement and democratic accountability. Mistakes were made and there was a lot of displacement of communities,” he says. “That focus on community and neighbourhood involvement is something that has evolved since Abercrombie.”

Perhaps, the days of figures such as Abercrombie are over. “These famous plans were usually attached to a man’s name – Abercrombie, Burnham,” says Patrick Philips. “These days there isn’t a single visionary, godlike planner. PlaNYC, for example, wasn’t called the Bloomberg Plan.”

——————————————-

Urban visionaries through the centuries

Dinocrates – Alexandria, Egypt (4th century BC)

Dinocrates was the Greek architect who pioneered the grid style of street layout that is so familiar to modern American city dwellers. He also oversaw the creation of the Greek empire’s second-greatest city from what had previously been marshy delta where the Nile meets the Mediterranean.

Philip Jackson – Singapore (1822)

British swashbuckler Stamford Raffles, who founded Singapore in 1819, commissioned Jackson to draw up a plan whose zonal layout survives in its essence to this day. It separated civic functions, business and residential areas, although rapid population growth meant that swaths of suburbs were soon needed. Its fundamental organisational concept of racial segregation has since been abandoned, however.

Georges-Eugène Haussmann – Paris, France (1850-1870s)

Commissioned by Napoleon III, Haussmann demolished Paris’s overcrowded medieval slums and replaced them with wide boulevards that were too broad to barricade. This made it easier to put down armed uprisings. “Paris hacked about as with a sabre, its veins opened, feeding a hundred thousand navvies and masons,” wrote novelist Emile Zola, complaining that the plans brought “forts right into the heart of the old quarters”.

Daniel Burnham – Chicago, US (1909)

One of the first regional city plans, the Burnham Plan sought to create large-scale mass transit, including a highway system and freight and passenger rail improvements. It also envisaged an outer ring of parks, a more systemic pattern of streets, and the creation of a civic centre of government and cultural institutions. Burnham envisaged Chicago as “Paris on the prairie”. He also worked on plans for Cleveland and Washington DC in the US, and Manila in the Philippines.

PlaNYC – New York, US (2007)

Then-mayor Michael Bloomberg aimed to turn New York into the first environmentally sustainable city in the US. His PlaNYC project also set out to prepare for a 1m population increase, and the repair of vital infrastructure such as bridges, public transport, the power grid and water mains. Practical achievements included the conversion of taxis to clean fuel, increased spending on energy efficiency measures in public buildings, new bicycle lanes and the clean-up of the city’s waterways. A proposal to introduce congestion charging was not implemented

Kate Allen is the FT’s property correspondent

Photographs: Hulton Archive/Getty; Planet News Archive/Getty; Urban Images/ Alamy

Comments