The Shrink & The Sage: How mindful should we be?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Shrink

Have you done your 10 minutes of mindfulness today? If you don’t know what I’m talking about, mindfulness is a meditation technique with Buddhist roots that involves training ourselves to become more attentive to the thoughts and emotions that make up our stream of consciousness, the ever-shifting present moment. If you have heard of it, you may be part of a growing army of people who have woven into their daily life a method, now complete with celebrity endorsement, which used to be the preserve of silent retreats.

Even back then, people’s motives were always somewhat mixed: the wish to gain some kind of spiritual insight, if not full nirvana, would have probably been part of the mix. But it has been several years since mindfulness came down to earth, transformed into a fully evidence-based approach, adapted to clinical settings and married with neuroscience. Its effectiveness in working with stress, chronic pain and depression has been demonstrated, as well as a host of psychological benefits. The Oxford Mindfulness Centre describes itself as “preventing depression and enhancing human potential by combining modern science with ancient wisdom”. Nowadays it is health, or mental health, concerns that are more likely to motivate people to engage in mindfulness.

Try as I might to play devil’s advocate, I can’t find the drawbacks to mindfulness. In fact, it can also have a host of other benefits. For instance, by learning to be more aware of the constant stream of impulses arising in our minds, and less identified with them, we can become better able to choose whether to act on them or not. When we’re mindful, our life can be more autonomous.

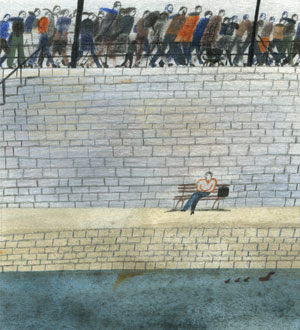

And yet, it’s a shame to reduce mindfulness to a means to an end. It’s good to be mindful in order to be healthy and self-directed but we should also be mindful just in order to be mindful. Sitting quietly paying attention to your breathing needs no further justification. And slowing down to notice things rather than speeding past them makes for a much richer and more nuanced life experience. Try it.

…

The Sage

I’ve heard a lot of mighty claims for mindfulness over recent years, setting off one of the most reliable thought alarms of all time: if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. But unless you’re an expert on what is being bigged up, how do you know where truth ends and hype begins?

The answer is suggested by two principles that experience bears out time and again. The first is that when it comes to how best to live, there is no magic bullet. However useful a particular tool might be, it’s just another one in the box, not a kind of skeleton key to unlock all life’s problems. Without knowing anything at all about whatever the latest saviour of human wellbeing purports to be, you can be pretty sure that it won’t be the answer to all our prayers.

The second is that since there is no algorithm for living, if something is useful, then it is highly unlikely that any one person or group owns the right way to use it. Mindfulness in its most general sense is simply a heightened awareness of ourselves, our environment, what we are doing. Buddhists have their own ways of practising it and some cognitive-based psychotherapists have been developing ways of incorporating it into their practice. But if it is indeed a good thing, then no one is going to have a monopoly on it. There are many ways of being mindful, not just the proprietary methods developed for specific spiritual or therapeutic purposes.

This illustrates how something being “too good to be true” is not a reason to dismiss it cynically but to ask how good it could be without being false. The reason why many things attract excitable, exaggerated claims is that they often have something genuinely good going for them. It would not be at all unbelievable if mindfulness turned out to be useful, something that can improve the quality of your life, perhaps significantly. Just be mindful of the perennial mistake of zealots everywhere, of elevating a good to the good, inevitably making it worse, not better.

The Shrink & The Sage live together in southwest England. To suggest a question, email shrink&sage@ft.com

Comments