Saying goodbye to God: Haredim apostates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

About five months ago Yossi Jacobs, a young Israeli, sat down and wrote a letter to God. Yossi had recently become an atheist but his words had the tender tone of a love letter. “I miss you terribly, though I know that you never existed,” he wrote. “You were a friend, brother, father, educator, partner and lover. You were everything for me and you never left me alone.”

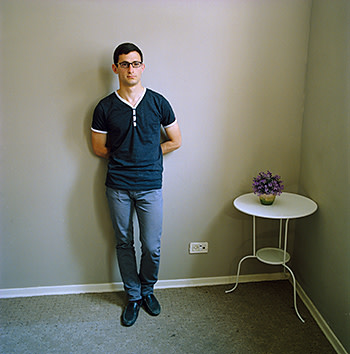

Yossi, 25, has hipsterish glasses, an amiable smile and an anxious demeanour. At an age when most other young Israelis are at university or taking an alcohol-fuelled gap year after military service, he has a wife and year-old daughter and needs to find his place in the world soon. Until recently Yossi was a member of Israel’s close-knit ultra-Orthodox community: the Haredim.

This arch-conservative group accounts for about one in 10 Israelis (more than 750,000 people). They strictly observe Jewish law and customs, including codes of modesty in dress, and avoid socialising with non-religious Jews; in their approach to scripture and religious observance they might be described as fundamentalists. In a country where more than 40 per cent of people identify themselves as secular, the Haredim devote themselves to God, inhabiting teeming neighbourhoods such as Jerusalem’s Mea Shearim or Bukharan Quarter. They ride “kosher” buses where women self-segregate by sitting in the back. The ultra-Orthodox are overwhelmingly likely to subsist on public benefits, with 70 per cent of their households living below the poverty line.

As a result, the Haredim are at the centre of Israel’s most heated public policy debate as Benjamin Netanyahu’s government tries to pull them into the modern world through new legislation and social engineering. Netanyahu’s coalition promised voters “equal sharing of the burden”, shorthand for making Haredim work and serve in the military, the revered national institution of Israeli life. “You can’t have a tenth or more of the population that is supported by the rest of the population,” says Dov Lipman, an ultra-Orthodox rabbi who heads a Knesset task force on integrating Haredim into the workforce. “It’s a tragedy that people are living in poverty for no reason.”

While ultra-Orthodox communities in the US and elsewhere successfully coexist with the dominant culture, Israel’s Haredim present a special case because of the community’s unique history in the Jewish state. When the ultra-Orthodox began arriving in Palestine in the late 19th century, they were sustained largely by overseas Jewish donors. But as Zionism’s early pioneers, many of them secular, came to dominate life there, the ultra-Orthodox secluded themselves. After the Holocaust, when most of their European communities were destroyed, they devoted themselves to regenerating this lost world through prayer and Torah study at Israel’s yeshivot (religious seminaries).

The Haredi parties became kingmakers when the Israeli rightwing rose to vanquish the leftwing leaders from the 1970s. In exchange for making up coalition numbers on both sides, they exacted generous perks from the public purse, including child benefit grants to sustain the large families they felt they needed to produce to regenerate the depleted ultra-Orthodox world.

No longer. Today policy makers voice concern that Haredi men are putting an unsustainable strain on Israel’s innovation-focused “Start-Up Nation” economy. With the Knesset’s religious parties locked out of cabinet for the first time in recent Israeli history, the Netanyahu government this year passed a law phasing in the draft for most Haredi men by 2017, to overwhelming approval from the public and defiant mass protests by Haredi groups.

The prime minister has slashed benefits for the ultra-Orthodox as well. More than half of Haredi families have four children or more while their offspring account for 19 per cent of the total enrolled in Israeli schools, an indication of their status as the fastest-growing demographic in Israeli society. If this trend continues, the costs of supporting the community could even threaten Israel’s sacrosanct $16bn-a-year defence budget and, with it, its ability to defend itself in an unstable region.

“The trajectories here are unsustainable,” Daniel Ben-David of Jerusalem’s Taub Center, a leading economist, told me recently. “If you are giving about half the kids in Israel a third-world education and those are the groups that are growing the fastest, you are heading toward a third-world economy.”

…

While the government focuses on helping Haredim square religious and lifestyle edicts with the modern economy, some ultra-Orthodox are choosing to leave the faith entirely. I met Yossi through Hillel, an Israeli non-governmental organisation that helps this minority in their adjustment to secular life. Because of the austere, theocentric education they receive, many ultra-Orthodox have little grasp of maths, science or English, the lingua franca of Israel’s global high-tech economy. Indeed some, raised in branches that reject Zionism, do not speak Hebrew, Israel’s state language, knowing only Yiddish.

Named after a famously lenient rabbi, Hillel has an office in Jerusalem’s centre, an upstairs hall that has the earnest, potluck feel of an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. There, alongside Yossi, I got to know three other young people who had chosen to leave the faith – a process often accompanied by nearly unbearable stress, social ostracism and the pain of losing God after growing up in a community that puts the deity at the centre of everything. Their stories differ but there are a few common threads. First the questioning starts, then there is an abrupt, often forced departure from school or home.

“I felt suffocated,” Ori Becher told me. Ori is an outgoing young man of 20 with blond hair, who sometimes sports the fashionable stubble typical of young Israeli males. He was telling me about his yeshiva, where he studied the Torah from 7am to 7pm every day. “Why do I have to suffer?” he recalls thinking at one point. The trigger that caused Ori to leave “Torah World”, as Haredim call the cloistered subculture of scripture study, came when his yeshiva declined his request to visit a gym in the evening to practise martial arts. He moved to half-time studies, then quit the school. When his parents found out they kicked him out of the house.

All the ex-Haredim I met struck me as engaging, brighter-than-average people. They had an earnest intensity I had seen before in other hothouse contexts: gay men coming out in the 1970s, for example, or eastern European dissidents speaking truth to power behind the Iron Curtain in the 1980s. They sat uncomfortably in their newly inhabited non-religious frames, looking like recent graduates wearing suits and ties for the first time.

Clothes are part of this story. Because some of the young people are disowned by their parents when they reject religion, they arrive at Hillel with nothing more than the garments on their backs: black suits and hats for men; long skirts and wigs or other head coverings for women. The NGO keeps a closet of donated casual wear for the ones who literally do not know how to dress on their own.

“It’s like they land on the moon,” Ruti Bavly, a Hillel volunteer, told me. “They cut their relations with their family most of the time; they don’t tell their friends and they are all alone.” Ori showed up in a tank top for one meeting on a cold, rainy day; at another, this masculine young man was carrying a flowery umbrella belonging to his grandmother, with whom he now lives.

To leave a Haredi household brings both boundless opportunities and overwhelming challenges. Most Haredi families forbid internet and television.Sex is not discussed. If they use telephones, they stick to “kosher phones” offered by Israeli cellular providers, which allow calls and a calculator, but no internet or smartphone functions.

“It’s weird but it’s also wonderful: you have the euphoria,” Ori said of the freedom of entering a world where he could choose what to study, and meet girls. But there is disorientation too. “You don’t know how to speak to someone your age – the slang is different, everything is different,” he added. “You don’t have the tools to handle the world.”

…

Hillel mentors the apostates, who must be over 18 and pass a screening process to benefit from its help. It offers educational grants that help them develop the hard skills needed for the workplace, and the soft ones needed to write an email, make a phone call or apply for a job. “I could do two plus two but I couldn’t do eight times eight,” said Israel Lieberman, another of the young people I met at Hillel, when I asked him about his yeshiva education.

Israel, 21, found his way to Hillel after querying what he calls the “bad stuff” in the scripture – the holy writ on people who don’t keep Sabbath, or are gay. Around the same time he was asking these questions, he realised that he himself was gay – forbidden among the ultra-Orthodox – although he said this was not why he had left. “My going out of the religion was because I didn’t believe in God,” Israel told me. When he asked his rabbis about two conflicting versions of the creation story in the Torah, he was thrown out. “It was good for me,” he told me later. “I saw they were trying to lie to me.”

Israel, like other ex-Haredim, struggled with secular life skills such as learning to dress: he recalls putting on a white shirt with white trousers, before a friend put him right. He enrolled in a college preparatory course, and now works part-time checking computer codes for a company. Next year he wants to study computer programming at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Israel began to read philosophy – Nietzsche, Descartes – at the library in Jerusalem. “I started to see that it’s not like the Orthodox say, that it wasn’t given by God – it’s given by writers.” Then, he said, “I felt very lonely.”

…

Indeed, some of the hardest challenges for the ex-Haredim – and those that can’t be addressed with donated clothes or college preparatory courses – have to do with the loss of God. Yossi remembers picturing one of the creator’s Hebrew names – which the ultra-Orthodox are not allowed to utter aloud – hanging in front of his face, overshadowing all he did. “One day I just popped,” he told me. “It was me trying to be perfect and make God love me and do the right thing – just driving myself crazy to please God.”

Yossi stopped following the rules, and soon dropped out of his yeshiva. He decided to join two older, more liberal brothers who live in New York. He bought some jeans and T-shirts and changed out of his black suit and hat and white shirt on the way to Ben Gurion airport. Yossi told me he felt both free and utterly devastated. “The hardest thing to get used to is the loss of meaning,” he said.

Some of Hillel’s most complex and painful cases involve women. If a female Haredi leaves the community without her husband, the terms of the divorce may require that her children remain in religious schooling. This can make for wrenching arguments at home.

Mirel Mark became secular four years ago, and is still battling her former husband. Mirel speaks Hebrew with a lilting accent because she only recently learnt it. She belonged to the Satmar community, a branch of the ultra-Orthodox who reject the Jewish state as an affront to the coming of the Messiah. Such anti-Zionist groups particularly infuriate secular Israelis, frustrated that they disown the state of Israel but gladly cash its benefit cheques.

Mirel, 32, was betrothed at age 19 to a boy of 17 she had met 30 minutes before. “I didn’t have a choice – my parents introduced him, and said ‘You have to marry him.’” Initially, she recalled feeling “excited” at leaving home and giving birth to her daughter Rivki, now 11. But then Mirel began to ask typical teenage questions – as she describes them – about the world: Who am I? Why do I do what I do? This led her to ask her husband for a divorce.

Mirel had no access to the internet but, through a friend, found her way to Hillel, who advised her to seek the divorce in a state court, not a rabbinical one. She gained custody but said she has been harassed. “I get a lot of threats from the community – threats to my life; they said they would kidnap my daughter,” she told me. The day we met, she said she found a small camera planted in her flat.

While ultra-Orthodoxy is ostensibly an all-or-nothing proposition, there is a middle ground of Haredim who question the faith but never make the leap to leave. Their numbers are impossible to estimate but there are internet forums such as “Forced to be Haredi” and soirées or Shabbat dinners for these people, who then go back to their communities. Those who do make a clean break risk tainting their families’ name. As Ori explained, a boy who leaves the faith will “lower the value” of his sister on the marriage market. A family’s reputation can be broken if someone leaves; other families will talk.

Apart from external social pressures, ex-Haredim face other sorts of stress, most notably the challenges of absorbing consumer culture – and developing appropriate filters – for the first time as a young adult. Social media, a novelty for anyone leaving the ultra-Orthodox world, amplifies the tensions. “When you are hungry and are thrown into a banquet with 40 types of bread and 60 types of cheese, what are you going to eat?” Jose Benarroch, a psychiatric social worker who volunteers for Hillel, told me. “This freedom can be as much a prison as the prison they come from.”

The ex-Haredi community was hit hard recently by a spate of suicides, culminating in the death of M (who has not been named publicly) in January. He was the latest of seven former Haredim to have killed themselves in the past 18 months, three of whom belonged to Hillel. (Israel generally has a very low suicide rate.)

According to the liberal newspaper Haaretz, M was clinically depressed before he left the Haredi world; Benarroch, who met him, confirms this. However, friends say, he was pushed over the edge when he showed up uninvited at the Jerusalem engagement party of his brother, who shunned him. One of his friends told Haaretz afterwards: “After another one [ex-Haredi] commits suicide, I’m next.”

…

Some of the Haredim are actively resisting secular Israel’s attempts to pull them into the modern world. A few weeks before I met Ori, Israel, Mirel and Yossi, I attended a demonstration of more than 300,000 Haredim – a significant portion of Israel’s eight million-strong population – at the western approach to Jerusalem. Billed as a prayer service, the mass gathering was meant to serve as an angry show of defiance after government passed the bill subjecting the ultra-Orthodox to the draft.

Gidon Katz, a spokesperson for the event, told me that Torah scholars were as vital to the Jewish people and their 3,000-year history as Israeli soldiers manning the front line. “They are trying to pass a law that would split Israeli society into two,” he said.

Away from the hue and cry of those resisting change, however, some Haredim are quietly beginning to respond to the changes in their economic status and the pull of the modern world. “There is no hermetic community today,” Rabbi Jonathan Rosenblum, a modern Haredi rabbi and journalist, told me. “Any kid can go out and get himself a phone. There is no way to shut up; we live in a mixed society.”

The Haredim, Rosenblum says, are also recognising increasingly that English is a necessary tool. Growing numbers of Haredi women – less bound to the life of scripture than their male counterparts – are finding an economic niche, including jobs that pay them competitively low wages in return for the right to work in a single-sex, closed environment near their home.

In one sign of the untapped economic potential of the community, Jerusalem Venture Partners – one of Israel’s biggest venture capital groups – recently held its second annual Haredi high-tech conference, showcasing success stories from companies, angel investors and Israeli officials.

Yossi is finishing a car mechanics course, not out of passion – he loves writing, and published his letter to God in Hillel’s magazine – but because it is a practical skill. He is still struggling with what he calls the “culture shock”. Adjusting to life is “not terrible, but very hard”, he told me. “I still find myself asking, ‘Where is the meaning, what is the purpose?’”

Meanwhile, Israel has expanded his reading to Richard Dawkins, who he says is “too focused on biology, but has a good brain”. He is questioning life in Israel, too – mainly the country’s relations with the Palestinians – and thinking of emigrating to the UK. “The same arguments everyone used to use against the Jewish people I hear against the Palestinians,” he said. “It makes me feel guilty.”

Ori is preparing for university, where he wants to study economics. Unlike the other boys – or Mirel, mired in conflict with her husband – he dwells on the positive side of his new freedom. “Once I realised I didn’t have to do all those things – I don’t have to wear the black clothes; I don’t have to study all day – it’s like changing your belief so instantly,” he said. “So fast, it’s shocking.”

John Reed is the FT’s Jerusalem bureau chief

Photographs: AFP; Michal Chelbin/INSTITUTE

Comments