Social network of the damned

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Hell is other people, wrote a famous French philosopher, who proceeded to hang out in crowded cafés all day long to show off his tricksy ways with a paradox.

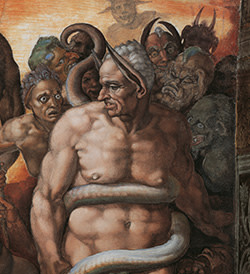

Jean-Paul Sartre was not alone in his perception, although he put it more boldly than most. Our visions of the burning place are indeed replete with bad company: crazed demons, fellow sinners, assorted exotic and frightening reptiles. In Michelangelo’s “The Last Judgment” in the Sistine Chapel, a figure with donkey ears is bitten in his private parts by a coiled snake, leaving us menfolk to ponder the subtle metaphysical question of which is the greater humiliation.

On YouTube, a South Korean woman displays her paintings of hell, having been taken there one fateful day by Jesus Christ himself. Grim viewing it makes: there are people with missing or flayed body parts, a man having rocks shovelled into his mouth, and a special corner for miscreants who have overindulged in “secular television”, in which a giant arm springs from a flatscreen set and squeezes the hapless viewers’ skulls to a pulp. (One day we will wonder why this lunacy was deemed acceptable for mass consumption, while the wholesome pursuit of mutually enjoyable sexual relations between consenting adults was considered taboo. But that’s one for the future.)

There are signs that our concept of damnation may be evolving into something quite different from an extreme version of a packed commuter train. In the Royal Opera’s visually striking new production of Don Giovanni, the opera’s climax, which normally sees the chastened – or perhaps not – seducer dragged into the flames of hell, is given a radical reinterpretation.

I have always found the ending of Mozart’s most complicated opera something of a problem, veering uncertainly between the bathos of clunky scenery and hammy acting, and something which tries to deliver a moral message, but doesn’t quite succeed. Mozart and his librettist Lorenzo da Ponte are more than a little seduced themselves by their protagonist. They can’t seriously want us to live happily ever after in the pallid world of Don Ottavio, the drippiest character in the whole of western culture.

In Kasper Holten’s production, there are no flames of hell for the reckless philanderer. Instead, as his dinner date with the undead takes a turn for the worse, he is gradually stripped of his entire world. The elaborate scenery turns plain, all technical effects are switched off. The stage is reduced to a simple backdrop, the house lights come on. He turns to the audience, and holds out his arm. His world is dead, because worldliness is all he has. Without others, he is nothing. Hell is no people at all.

…

The thought reoccurred just a few hours later when I watched the climax of The Bridge, the television series that is the most desolate of the Scandinavian noir genre, which is saying something. The Bridge is nominally about the investigation of crime, although its forensic gaze is applied still more intensely on the loneliness of the soul. We will its two protagonists, Saga Noren and Martin Rohde, to form a bond that will strengthen them, in the best tradition of cheap police drama. To share a wisecrack is to battle all that is malign in human nature.

There are moments of unusual chemistry between them. But they are both fundamentally alone, their lives stripped of most human comforts. Between them they have some serious baggage to contend with – a dead child, autism, failed marriages, Stygian evenings – and they ultimately fail. In The Bridge, the criminals might get caught, but the catchers are not afforded the luxury of satisfaction with a job well done. The betrayal of Martin by Saga in the final episode of the second series, a man haunted by what is inside his head undone by a woman cast adrift from empathetic response, is quietly shattering. Hell, here, is the inability to connect.

Sartre got it, of course. He explained his famous dictum, from his play No Exit, in a 1947 article: “We judge ourselves with the means other people have and have given us for judging ourselves. If my relations are bad, I am situating myself in a total dependence on someone else. And then I am indeed in hell.”

It bears thinking about, in the age of hyper-connectivity. We increasingly define ourselves by our relationship with the external world, which is fast and furious in its eagerness to condemn. But even worse than condemnation is neglect. Hell for me, professionally speaking, is for no one to read this column. Hell for anyone wishing to troll me is to be ignored completely.

It is solitude that is the infernal quality of today, not the plethora of fellow sufferers who crowd our hearts and minds. We are a mislaid text message away from damnation. Imagine life without the social network: it brings you out in a sweat.

——————————————-

peter.aspden@ft.com, @peteraspden

To listen to culture columns, visit ft.com/culturecast

——————————————-

Letter in response to this column:

Unfair to call Saga’s action a betrayal / From Mr Kevan Pegley

Comments