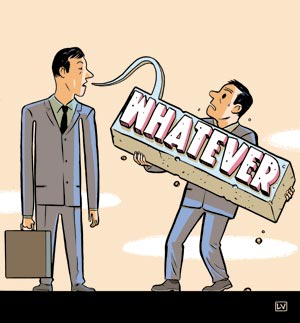

If in doubt, reach for the whatever

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

There are few more annoying expressions in the English language than “whatever” – delivered, for maximum effect, in a flat monotone which denotes that the speaker cannot even get agitated enough to add a touch of inflection to their response.

The beauty of “whatever” (sorry, that should be “whateva”) is its indifference to the recipient. It is like receiving a one-line standard reply after pouring out your feelings in a long and angry email. But then it is meant to be annoying, which is why it was invented by teenagers. Anyone with adolescents knows the power of “whatever”. Clearly, I discourage the spawn from the w-word at home, while recommending its use as the best response to playground barbs. This mixed message does confuse them but, well, whatever.

We all have “whatever” moments at work but, sadly, using it on colleagues or customers turns out not to be one of the seven habits of highly effective people. So we opt for the less obviously confrontational gems like the distracted “yeah”, “uh-huh” or the nuanced “I hear what you say”. (One colleague used to reply to angry letters with the phrase “perhaps you are right”. Few noticed its unstated inverse that perhaps they were not.)

On balance, we do not want this teenspeak creeping into our already puerile political discourse – although, on the upside, it would shorten Any Questions. The current crop of political leaders seem overly drawn to teen talk as it is. Both Ed Miliband and the prime minister talk of “getting it” – the Labour leader in the tones of a frustrated teen told to clean his bedroom. How long can it be till he starts flashing the “loser” gesture across the dispatch box?

But every now and then you know that “whatever” is the best response. Last week saw such a moment when allies of the Russian president goaded David Cameron by dismissing the UK as a small island of dwindling importance. There are only two possible responses to such barbs. The first is a put-down of Churchillian brilliance but these tend to be quite hard to come by – unless of course one actually is Churchill, which, statistically, most people tend not to be. The second is a version of the “whatever” response; a dismissive shrug, a curt “nonsense”.

Cameron chose neither. When asked by reporters about the Russian remarks, he ditched the optimal responses and went into the kind of lengthy panegyric about the UK that usually has “Jerusalem” playing in the background. Britain had, he said, essentially created every sport worth playing, every book worth reading and every song worth hearing. It had abolished slavery, defeated fascism and invented freedom. He went on (breaking new boundaries in what you could not make up) to cite the boy band One Direction as proof of our continuing contribution to world culture – which, when you think about it, goes somewhat to the Russian’s point. We were, I suppose, lucky he stopped short of claiming that the UK had invented “twerking”.

On and on he went; Britain did this, England did that. And the more he went on, the more I found myself thinking of Kevin Keegan, the erstwhile England soccer manager. Keegan, while manager of Newcastle United, famously lost his cool over some snarky remarks by Alex Ferguson when the two men’s teams were tussling for the league title. It cemented Fergie’s reputation for mind games and Newcastle went on to lose the title race. Likewise, the more Cameron spoke, the more it seemed the Russian had hit a nerve. Did the PM secretly share the view of a reduced UK, especially after the Syria vote, or was it just his own insecurities coming to the fore after a bad week and an inglorious summit? In fighting his own demons, he forgot to reach for the whatever.

I have long felt uncomfortable about the age of our political leaders. I fully expected them to be younger than me one day, just not quite so soon, and have long been looking for a reason to justify my hostility to the idea. Now, at last, that reason is clear. A prime minister needs to be old enough to have raised teenagers – if only so he knows the power of “whatever”.

Twitter @robertshrimsley

Comments