Is gender neutrality the way to shut the Stem gap?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When EDF Energy launched its “Pretty Curious” campaign in October aimed at “inspiring girls’ curiosity about science, technology, engineering and maths”, it probably did not intend to highlight the debate about the gender imbalance in the sciences. But that is exactly what it did.

Critics lambasted the apparent irony of using a stereotype to name a programme aimed at fighting stereotypes.

“I hate this presumption that Stem (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) stuff needs to be ‘girlified’ to appeal to women,” wrote Emily Schoerning, director of community organising and research at the National Center for Science Education in the US, adding that it draws attention “to our gender over and above our achievements”.

Last month, EDF announced the winner of its Pretty Curious science challenge: a 13-year-old boy. The company explained that, while the campaign was aimed at girls, the competition was “gender-neutral”. Another social media firestorm ensued.

Sue Black, a British scientist, took to Twitter in response: “I’d love to know: how is the winning entry seen by EDF to encourage girls into Stem?”

Women are under-represented in many professional Stem fields. According to the US census bureau, male science and engineering graduates are twice as likely to be employed in a Stem occupation than female ones. The commerce department found women represent roughly a quarter of the Stem workforce; in the UK, the figure is 14.4 per cent. Countless studies illustrate how unconscious and institutional biases, along with societal and familial pressures, inhibit how women scientists are perceived, encouraged and promoted.

Young women are narrowing the gap in participation in mathematics and science courses, according to the US department of education. But the question remains: should girls be singled out and encouraged to pursue and stick with Stem careers, or is the best route to equality gender-blind?

At 15, Ciara Judge was joint winner of the 2014 Google science fair for a project that studied how bacteria could boost low crop yields and fight world hunger. The Irish teenager offered a point of view shared, in particular, by some of her fellow young female peers. She wrote on her blog: “To those criticising the idea that a contest to promote females in Stem would have a male winner, I ask: is allowing a girl to win by default really a way to promote girls in Stem? There is no worse feeling on earth than feeling like your success is because of your gender.”

Nicole Ticea, 17, won the Intel Foundation’s Young Scientist award last year for developing a cheap, portable HIV testing device that delivers results within an hour. She says she did not notice gender imbalance in her pursuit of the sciences, in part because she attended an all-girls school.

She says: “I don’t know how effective these programmes are that target only young women solely for the fact that they are young women. I think it should be something that is consistent and mandatory for both genders in all schools.

“If you’re not highlighting the distinction between men and women . . . if you’re just having everyone do science, then I think that’s the only way we can overcome this inequality.”

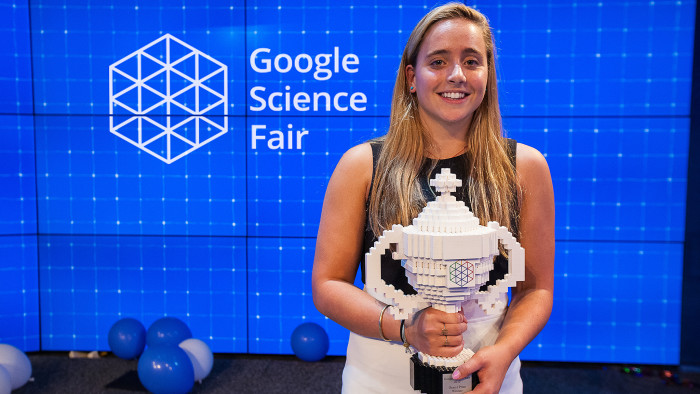

Seventeen-year-old Olivia Hallisey won the $50,000 top Google Science Fair prize last year after developing a low-cost, rapid detection Ebola test. She takes a more neutral view.

Ms Hallisey says her school in Connecticut “does a really good job of making it gender-blind”, and that the scientific research class in which she developed the Ebola test is roughly split between boys and girls. “I think that’s really important — since there are so many girls it helps, because sometimes girls get intimidated when they don’t see other girls.”

Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, head of the American Medical Women’s Association, says a lot of women feel pushing for equality is “old school stuff — even my daughter says we’re all equal now.

“Well, no, we’re not. We’re not making as much, we don’t have the same opportunities, there are times when someone looks at you and says, ‘you’re a cute girl, I don’t think you can do it’ — it doesn’t matter that it’s not a stated fact, it’s more subtle.

“It isn’t until it hits you in the face that you realise it.”

For our launch podcast episode - on feminism - of FT Irreverent Questions with Mrs Moneypenny go to the FT site or the Itunes site

Comments