Collecting with the FT: Martin Parr

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

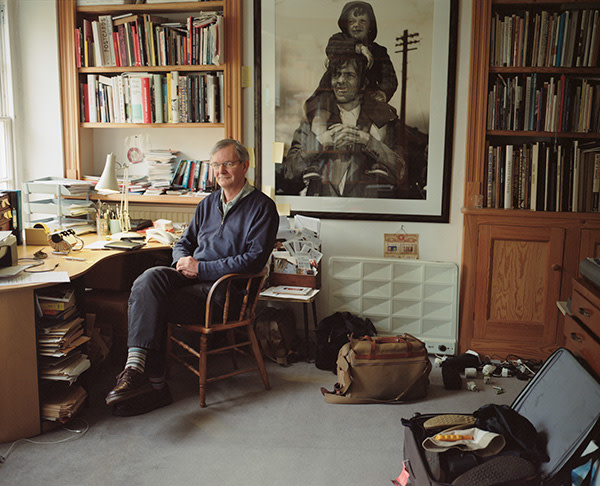

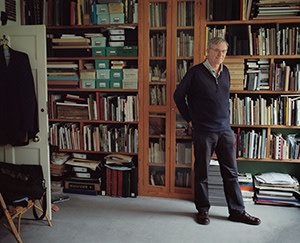

“Just look a little bit . . . happier.” It’s hard not to be amused by the hopeful upturn at the end of the sentence. Eva Vermandel is trying to take a portrait of Martin Parr, at home in Bristol, surrounded by his book collection. It’s not easy: partly because he looks so sceptical; partly because he keeps opening books up on the floor to show us, and so she has to keep asking him to stand up. After David Bailey, Parr is probably the best-known living photographer in Britain. His reputation derives from his candid pictures of others but he is also a dedicated exponent of the selfie – he may even have invented the term. His collection of self-portraits, taken in photo booths and studios all around the world, began long before the mobile phone camera was invented.

“You probably have to be an obsessive person to collect,” he concedes, “if you are going to do it seriously and thoroughly, which I attempt to do.”

We are here to talk about his books but Parr collects pretty much everything, from Chinese Mao-era tea caddies to miniature televisions, commemorative plates to cigarette cases decorated with Soviet space-dogs: “Yes, Laika, Strelka and Belka, they’re the three most famous . . .” That’s before you get to his print collection, some of which is in evidence on the walls as he leads us downstairs to the basement.

“China and Latin America down here,” he says, “well, some of China . . .” We go into a small room stacked with boxes and lined with shelves of books. “There’s Japan, but just propaganda, here . . . and Latin America overspill.” It’s too tight for three, so we go next door, where a cabinet holds some of his novelty watch collection. He points to a watch-face decorated with portraits of President Bashar al-Assad of Syria and his father Hafez. “Very rare, the Assad material.”

“Where did you get it?”

“eBay.”

Parr is in his early sixties and, alongside his reputation as a photographer, his most enduring legacy is likely to be the 12,000 photography books he has collected over the past 35 years. What began as a hobby has developed into a mission to change the way the history of photography is defined and understood.

As a collector, he has discovered, documented and promoted previously unknown areas of photographic bookmaking. Japan is a good example: until the 1980s, the Japanese photobook was a specialist area, reserved for a few maverick enthusiasts, historians and collectors. Parr is quick to acknowledge them but, once he discovered what was there, it was his own proseletysing that brought the Japanese books to the fore. “The main thing I’ve learnt,” he says, “is how lazy and narrow-minded our histories of photography have been, and how, with some investment and some application, there is so much to discover.”

His collection is not comprehensive. “I get sent a lot of books – I get sent a lot of bad books,” he says. “If I don’t want a book, I’ll give it away. But I also get sent some fantastic things.”

He has bought books ever since he was a student at Manchester Polytechnic in the early 1970s but he dates the beginning of his serious collecting to the late 1980s, “when I bought the original Robert Frank Les Américains, and The English at Home by Bill Brandt – some of the classics. As I started to earn more money, I got more hooked and, having cash from my relatively successful magazine and commercial career . . . You know, this is an expensive business.” A look on AbeBooks.com gives an idea of current prices: Les Américains (1958) at between $3,000 and $5,000 – a signed copy is $10,000. A first edition of The English at Home (1936) is around £300 to £400.

When I ask if he has estimated the value of the collection, he says, “I haven’t. But I know it would be substantial.” His critics are quick to point out that, in being one of its generators, he has also been one of the chief beneficiaries of the growing interest in photography books and the steep rise in prices. Isn’t he now competing in a bull market he has helped to create?

“Yes,” he says, “but, remember, I’m looking for things before anyone else is looking for them. That’s what’s happened in China. When people see what we’ve dug up from China, they are absolutely bog-eyed.”

In 2004, he published the first of two, soon to be three, volumes of The Photobook: A History, an edited selection of his collection, illustrated with layouts from each volume, written by his friend and collaborator, the photo-historian Gerry Badger. Initially pored over by photography fans, dealers and collectors, the volumes quickly became the handbook for auction houses, which often had little else to quote by way of provenance for a photographer’s work. Since then, the selective listing by Parr and Badger has encouraged an insider market among collectors, publishers and photographers, since inclusion in the history brings kudos to both publisher and photographer’s reputation and almost guarantees an eventual hike in the resale value.

In his study, a large print by his friend Chris Killip hangs over his desk. This is where he keeps his most recent acquisitions. He has “correspondents” in various countries who help find books, and a range of dealers who offer him things he might want. He believes that China is the last country with a true hidden history of photographic publishing. “The other candidate in Europe is Italy. I’ve just come back from a trip and I’ve got many books from the Italian fascist period.

“Now, let me show you . . .” He hands me a stapled pamphlet, badly printed in black and white. “Emmett Till – this is the first civil rights book ever . . . look, price $1, the first, and a factual photo story.” It covers the trial of two white racists from Mississippi who murdered 14-year-old Emmett Till, a black boy from Chicago, for flirting with a white girl. “Took me a long time to find that,” he says. “I had to spend £7,000 on it. And I’ve never seen one since.”

What does he want to happen to the collection? Where does he want it to end up? “Eventually I want it to go into a public collection, to be looked after and be used as a research tool. That’s the whole point really. There is no particularly good photographic book collection in the public domain in the UK.”

So if a private individual were to offer you a great deal of money? “I would decline,” he says immediately. “It’s not about the money.”

Of the possible venues – the V&A, the British Library, the Tate – he nods at the last one. “Well yes, it’s my preferred venue,” he says. “I’m in discussion with them, but nothing has been determined.”

Simon Baker, the Tate’s curator of photography, says: “Clearly, Tate is supportive. The photobook is absolutely at the heart of the history of photography. In our exhibitions, we place books in the gallery alongside prints. We’ve already put our marker down.” And anyway, he adds: “Whichever institution gets it, they will have the greatest photobook collection in the world.”

“The Photobook: A History Volume III” by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger is published by Phaidon on March 17. The authors will be speaking at Photobook Bristol, June 6-8. www.photobookbristol.com

To comment on this article please post below, or email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments