The Diary: Tom Rob Smith

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Newly arrived in New York, my first task is to find a good spot to write. I plump for a downtown bookshop, Housing Works, on Crosby Street. Though it is a charitable venture, using the income it generates to support people living with HIV, there’s nothing high-minded about my choice of location. I like it because the space is calm, shelves stacked with an eclectic range of second-hand books.

I’m here to write an episode of my contemporary spy thriller series recently commissioned by the BBC. It feels vaguely treacherous working on a show called London Spy in New York, as if I’ve defected with a satchel full of intelligence secrets.

Exemplifying the community spirit of Housing Works, there’s a sign, above the wicker basket of free condoms, reminding customers that the tables are intended for sharing. Forced to overcome my territorial instinct, I settle on an occupied table at the back, near the rare editions.

It’s a strange sensation, writing in public – there’s a performance to it, you can feel people wondering whether you’re merely affecting the pose of a writer, whether you’re being hopelessly naive, or if you’re working on something real. No one, including the writer, is ever quite sure which category they fall into.

My progress is steady for a few hours until I begin eavesdropping in earnest – debates about whether pain is a state of mind (surely not, I almost interject) and a new series called True Detective with Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson. As a way into the conversation, I consider mentioning that I met that show’s writer, Nic Pizzolatto, at a thriller award ceremony a few years ago. In the end I say nothing, reinforcing my position as the least charismatic member of our table.

I peruse the bookshelves and purchase a handsome edition of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man. With second-hand books I’m always hoping to discover some annotation in the margin, a declaration of outrage, or love, an incisive note by a brilliant student, but this edition is clean as a whistle. I can’t help but feel disappointed. I immediately add, in pencil, on the inside cover, “To Crosby, love Tom”. A cheat, I admit, but I’m a fiction writer, and enjoy the idea of someone 50 years from now wondering about our relationship.

…

I’m at the International Center of Photography (ICP) on 43rd Street to see an exhibition of Lewis Hine’s career. Hine (1874-1940) pioneered photography as a form of social commentary, documenting the conditions of New York building workers and the widespread practice of child labour. A guided tour is provided by my occasional research partner Zoe Trodd, the cleverest person I’m lucky enough to call my friend. I concentrate hard on making smart-sounding observations, my concentration providing me with the sudden realisation that earlier in the morning, as I was throwing out some rubbish, I also discarded a spare set of keys to my apartment that had been returned to me in an envelope. Worse still, my address was written on the envelope.

I profusely apologise, excusing myself from a bewildered Zoe, explaining I’ll be back in 30 minutes. I take the subway to Canal Street where I jump off, running in the direction of Chinatown, to the rubbish bin on the cross-street of Canal and Lafayette. Reaching into the bin I ignore the crowds and the spectacle I’m making of myself, rooting through until I find the envelope. The keys are not there. I resume rooting until I find the keys, clutching them with immense satisfaction. I run back along Canal Street, returning on the subway to the ICP. I finish the exhibition, red-cheeked with exertion.

…

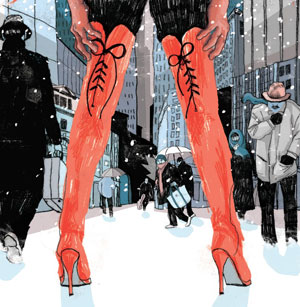

I am meeting my New York editor and his wife to discuss the launch of my new novel The Farm. In an attempt to increase the marketing spend, I use front row seats to Tony award-winning Broadway show Kinky Boots as a form of bribery. Disregarding the polar weather, I walk from Crosby Street to 46th, wearing three jumpers, a fleece, and four pairs of socks. Even with my dense padding, New Yorkers appear distinctly unimpressed by my ability to handle the cold, and several kindly advise me how to dress, commenting on the inappropriateness of my shoes and the absence of a sturdy jacket.

Kinky Boots started life as a modest 2005 British film (starring a then little-known Chiwetel Ejiofor) about a shoe factory in Northampton trying to save itself from bankruptcy by producing fetish shoes. There’s something quite remarkable about its transformation from a near-forgotten film seeped in British peculiarities into a hugely successful, cross-generational Broadway show, with top price tickets being snapped up for more than $400. But it is easy to see why: Cyndi Lauper’s music is sensational, Harvey Fierstein’s book is witty and warm, and the titular kinky boots are spectacular.

As I watch drag queens dramatically drop into the splits, I slyly assess my editor’s expression, trying to gauge if my bribery has been effective. At the end, he and his wife give the show a standing ovation but I’ve learnt this means little in New York. Almost everything and everyone gets a standing ovation.

The real test will come at publication, whether my novel secures that ad in the New York Times book section or if I receive a polite email explanation of how traditional marketing just isn’t as effective as it used to be.

Tom Rob Smith’s new novel, ‘The Farm’ (Simon & Schuster, £12.99), will be published on February 13

Comments