Where to try Olympic winter sports

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Pine trees and chalets draped in duvets of fresh snow, a graceful swish of skis on powder, the multilingual murmuring of perma-tanned sophisticates: on a windless, blue-skied January afternoon, everything about the French resort of La Plagne expresses the Alpine season’s bracing glamour. Everything except the mile-long corridor of grubby concrete, sheathed in translucent tarpaulin, that spools waywardly down the mountainside beneath.

Yet, in truth, the bobsleigh and luge track is La Plagne’s purest and most faithful embodiment of winter sport, the direct descendant of a recreational activity that began with spirited British Victorians racing each other down the frozen streets of St Moritz on anything they could find to sit on. As the local schoolchildren slipping about in their frozen playground so gleefully prove, winter sport is the indulgence of a fundamentally juvenile urge. Slide down big hills all day if you must but at least have the emotional honesty to yell “Wheeeee!” while you’re doing it.

Constructed for the 1992 Albertville Winter Olympics, the La Plagne track is the only luge track in France, and one of only 17 in the world. Nevertheless, most locals have resisted the sport’s crude excitements. So, too, the seasonal visitors, drawn here solely by the Paradiski area’s yawning pistes: 425km of uninterrupted skiing, facilitated by double-deck cable cars linking La Plagne with neighbouring Les Arcs.

The artificially refrigerated track is hardly cheap to maintain and, following years of underuse, it had, until this season, taken on the look of a white elephant’s long and twisty trunk. Now, after bold and heavy investment, the authorities hope to welcome a new breed of visitor, or at least to offer the old breed a lucrative novelty. Anyone with €107 to spare can now barrel down the 1.5km track’s 19 sweeping curves alone on a “speed luge” (fitted with a protective cage to protect even the most inept novice), or in company aboard various secure derivations of the bobsleigh. At the same time, three-time Olympic luge finalist Maija Tiruma has been brought in to coach local youngsters and enthuse them, with the long-term view of improving France’s abysmal record in winter track events, with just a solitary bobsleigh bronze to its name.

Not to be confused with the chin-to-ice skeleton bobsleigh, the luge is a feet-first submission to low-friction gravity. It’s a sport dismissed by detractors as “extreme sledging”, and underplayed even by its own participants, who with studious deprecation call themselves “sliders”. It’s also brutally dangerous.

“Speed is very high and time is very short,” says Tiruma, the Latvian former champion, summarising the challenge of her sport. “When a slider fights for one-thousandth of a second at 150kph, of course there is risk. So crashing is normal.”

As Tiruma elaborates on this theme I begin to find the luge’s unpopularity immediately less mysterious. At Vancouver, the last of the Winter Games that she competed in, Tiruma saw a Georgian competitor die after being flung off his luge and into a steel post at terrifying speed. Tiruma herself spent a month in hospital after smashing into the low roof of a track in Italy. At 150kph, a layer of Lycra doesn’t soften the blow.

She leads me up through the deep snow to the track, then parts the tarpaulin curtain at the apex of a curve. I peer in to see the frosted half-pipe gloomily revealed, its upper reaches scored by speeding steel. A distant hiss abruptly swells and, in a colourful flash, a prone athlete shoots past our blue noses, high up the banking. The American Olympic squad, explains Tiruma, is here for final pre-Sochi training. So, more arrestingly, is the Indian team, in the shape of Shiva Keshavan. “I come from near the Himalayas,” he tells me later. “My first luge was a sheet of corrugated iron.”

We wait for the session to finish in a cosy trackside hut filled with the stuff of sliding. The luges stacked around us are surprisingly hefty, torso-sized scoops of fibreglass mounted on meaty, low-slung steel runners. As described by Tiruma, the après-slide scene is monkishly sober, centred on solitary vigils in sheds such as this, smoothing one’s steels with files and extremely fine sandpaper.

On her instruction I try one of the luges for size. She tells me that the stubby handles in its fundament play no part in the steering process. So what does? “It’s difficult to explain,” she says, wrinkling her nose. “Just really small kinds of instinctive movements with the hips, the calves, the shoulder blades . . .” This is a sport that demands a rare blend of attributes. After an explosive start – four or five mighty shoves down on the ice from a seated position – the slider must throw him or herself flat on his back and settle instantly into a hyper-focused calm, at one with the track while pulling 5Gs round its hairpins. “If you turn into a corner 10cm too early or too late, you go too high or too low round the banking. Even if you don’t crash, your time is destroyed.”

At the Olympics, competitors make four runs with each one counted: one tiny error of judgment and four years’ work slides down the icy pan.

“OK, I can see this red luge is a little too small for you. Try that orange one.” With these words, an uncomfortable truth dawns: though I’ve come expecting to sample only the caged, idiot-proof “speed luge”, it is now clear that Tiruma is here to push me off down that steepling tunnel of ice in an uncaged, terrifyingly real one.

After a good hard gulp, I pull a Lycra onesie over my clothing, bully my head into an open-faced helmet and struggle to stay upright on a pair of special shoes. Their pointy-profiled soles are good for cleaving through the air when you’re lying down on a luge, and even better for making you repeatedly fall over when you aren’t. I totter foolishly about while Tiruma painstakingly erodes my steels, the luge upturned on a work bench. “A round edge is what we like to make – it’s the fastest but also the least stable.” She squints closely at her handiwork. “For you, I have made a sharp edge.”

There’s more welcome news when I learn I’m to be launched from two-thirds of the way down the track rather than its distant summit. We’re cooped up in the starting shed at bend 14 when a siren signals that the track is clear. As I lower myself into the luge, Tiruma tells me that, from here, I won’t be going fast enough to need to steer. “Just keep your shoulders down and stay flat,” she says. I lie back and think of Latvia.

What follows, according to the timekeeper’s printout I’m later handed, is 35.138 helpless seconds of judder and swoosh. For the first two of them I’m just lying down on a sledge. Then speed builds and the track corkscrews and it’s a water-slide, a rollercoaster, a freefall plummet to frosted destiny. I hurtle down the end straight like a man being shot from a giant frozen cannon.

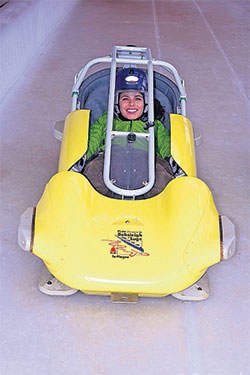

Later, when I have my turn on the speed luge, I start from the very top and hit 100kph, g-force pleating my cheeks and pressing me hard into the caged-in seat. My open ride hadn’t been even half as fast but with those walls of ice so very close to hand, the experience was unquestionably more exhilarating. So exhilarating that I jump straight out of the speed luge and beg Tiruma for one last go on the real thing.

This time I lay flatter, and thus go faster. Fast enough to just brush the right-hand ice exiting the final bend, which proves sufficient to send me ricocheting wildly down the home straight, battering from wall to wall. My luge slows, stops, then begins to slide backwards down the slightly uphill finish. I lie there with a bruise the size of a pita bread on each shoulder, a sleeve full of watch fragments and bottomless admiration for the sliders of Sochi.

——————————————-

Details

Tim Moore was a guest of La Plagne (laplagne.com). The speed luge and bobsleighs are available for public use from 4.30pm to 7pm every day except Monday. Le Cocoon (hotellecocoon.fr) has doubles from €200. The nearest airport is Geneva, a two-hour drive away

Watch footage of La Plagne’s speed luge in action…

——————————————-

Ski-jumping: like a corpse fired from a catapult

The hardest thing is the letting go. I am alone at the top of the K30 ski jump in Saalfelden, Austria, perching on a metal bar and staring down at my skis. They are vast – almost two and a half metres long – and are clipped to my flimsy lace-up leather boots only at the toe. The skis sit in parallel tracks made of solid ice that fall away before me for 60 metres, then end, like a pirate’s gangplank, in thin air.

My heart races; time seems to slow. I hear the faint lowing of nearby cattle. I become aware of my instructor, a tiny figure at the bottom of the slope. He is dropping his arm – the sign for action – once, then again, faster. But still my hands grip the metal bar.

It is my second day at ski jump school, and first attempt at the midsized K30 (the figure is the distance in metres from take-off to landing zone). Already I know that while ski jumping proficiency requires minute aerodynamic adjustments and split-second timing, for novices the most important thing is dealing with the fear. “I honestly thought I was going to die,” said Eddie “the Eagle” Edwards of his first forays into a sport that would later win him worldwide fame.

The terror had begun early the previous day, with a ride on Europe’s largest ski jump simulator, a huge metal tower that pokes up above the green fields near Höhnhart like an invader from War of the Worlds. A 200m-long cable stretches from the tower to the valley below and with skis on your feet you whizz down it, dangling in a harness below a mechanism of motorised pulleys. From there, we had relocated to the stadium at Saalfelden, where my coach, Florian Greimel, introduced me to the kit – soft boots like a boxer’s, skis like floorboards, suit like an adult babygro – and we began basic drills on an almost flat section of snow. “It’s all about precision and control,” he said. “It’s actually very much like golf.”

Greimel filmed each attempt and after a while we paused to watch the footage. This was an invaluable learning tool but punctured my balloon somewhat. What had felt like flights of growing length and grace were, in reality, over in a split-second and a couple of yards. In my mind I was starting to assume the poised, forward-leaning position of an accomplished jumper. In truth, I was stiff as a board, like a corpse fired from a catapult. Greimel did his best to reassure me, “and tomorrow if things go well, maybe you can try the K30 . . .”

Over dinner that night at the Gut Brandlhof hotel, we talked more about the techniques of ski jumping, then, perhaps less helpfully, watched some amusing crashes on YouTube. Greimel told me he eventually quit professional jumping because he got sick of dieting. Lighter jumpers fly further, so the sport’s stars were getting thinner and thinner until an anorexia scandal prompted the introduction of new rules on body mass index. I nodded sympathetically, then returned to the dessert buffet.

The morning brings heavy snow, and I am alone as I slowly climb the steps to the K30. Sitting awkwardly on the starting bar, I feel a growing sense of disbelief. Perhaps it just seems absurd that I’m allowed to be here; but there’s a sort of numbness, a sense of watching someone else rather than being in control. Finally, that person lets go of the bar and time suddenly speeds up.

There’s a surge of acceleration and adrenaline, an ecstatic moment in the air, then I’m rushing across the snow and skidding to a stop, relief washing over me, numbness replaced by a joyful tingling of every nerve.

Florian Greimel runs one- and two-day courses in various locations in Austria, from €95 and €240 respectively. See skisprungschule.com

——————————————-

Speed skating: ‘People call it Nascar on ice’

Inside the Utah Olympic Oval, an indoor speed skating arena just outside Salt Lake City, a former champion whips around a gleaming track. Derek Parra took gold here for the US during the 2002 Winter Olympics. Now 43, the Californian teaches novices how to speed skate. For a bargain $50, beginners of all ages, shapes and sizes can don the long blades and the Lycra and experience a slice of Olympic glory for themselves.

“A lot of people refer to speed skating as Nascar on ice,” says Parra, ominously, as I try to shoehorn my body into the unforgiving Lycra suit.

Discounting sports that use gravity or mechanical assistance, speed skating is the fastest self-propelled human activity, with top athletes reaching up to 40mph.

It is also, as I discover within seconds of stepping on to the track for my first lesson with Parra, a lot harder than it looks. Over the years I have tried skating at various public rinks but this is very different – instead of simply joining the unsteady procession of others, I head out on to empty ice, which, instead of being filled with ruts and bumps, is like a mirror. Parra runs me through the “fundamental movements” involved, the so-called “ones, twos and threes”. When linked, this sequence provides the basic momentum for speed skating.

The first position (the “ones”) begins in a crouch, before extending one leg out to the side. The second involves bending that extended leg under your body at a 90-degree angle, knee pointing straight down. The final position sees the extended leg driven forward to take your body weight, as the process repeats on the other side. “Put together, all three should propel the skater forward gracefully, gliding nicely on the follow through,” says Parra as I hop, limp and crash my way around the track.

By the end of our first session I am stringing together the movements, even if the sequences are punctuated by slapstick falls. The track caretaker, riding his tractor-like ice smoother, doesn’t seem too impressed with the amount of nicks and dents I’ve left in his pride and joy but Parra is happy with my progress. “Hey, I told you it was like Nascar,” he says. “If you want the speed on the circuit, you have to accept a few crashes.”

I retreat with aching thighs back to my base in the nearby ski resort of Park City – famous for its “champagne powder” snow, lively nightlife and the Sundance Film Festival – before returning for a second lesson with Parra the following day. This time, we work on “pushing out” with the skates rather than simply backwards as is the natural instinct.

Another drill involves skating around the rink pushing a bucket in front of me with one hand, while the other is tucked in the small of my back. “This is brilliant for teaching a more aggressive, aerodynamic position,” says Parra.

Slowly, a rough semblance of speed skating emerges; taking my first corner at speed is a real highlight and then, halfway through that second session, I get all the way round the 400m track without falling once. This is likely to be the zenith of my speed skating career but enjoying one-to-one tuition with an Olympic champion has been a rare treat.

For details of speed skating classes at the Utah Olympic Oval see utaholympiclegacy.com. For more on skiing in Park City: visitparkcity.com

Comments