Festivals offer a chance to turn on, tune in and pay out

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It rained on Burning Man this week, delaying the start of the experimental, utopian festival in the Nevada desert attended by many technology entrepreneurs and venture capitalists. Burning Man’s usual meteorological challenge is dust storms, so it made a change for the desert to imitate Glastonbury by turning to mud.

By Wednesday the sun had come out again and the 50,000 festival-goers were forming their traditional circular pattern of vehicles and tents as Burning Man got under way. Like other popular festivals – especially music festivals such as Glastonbury in the west of England and Coachella in California – it takes more than inclement weather to disrupt the summer celebrations.

Festivals are one of the biggest growth stories in live entertainment of the past two decades and they are still expanding, diversifying from pop, rock and electronic dance music into poetry and theatre. Many of the parents who paid for their teenagers’ attendance at the Reading and Leeds festivals last week themselves went to Latitude, a gentler cultural gathering in Suffolk, in July.

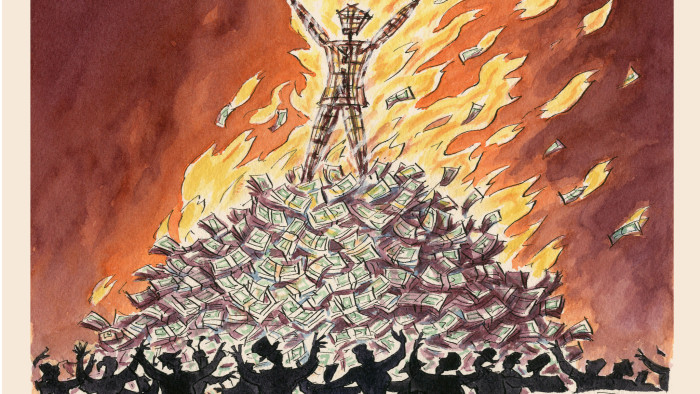

Festivals are enjoyed by all kinds of people, yet they are a paradox. Many have counter-cultural roots and some, notably Burning Man, try to be models of how society ought to be run. They are, as one study put it, “utopian havens” that provide a release from the pressure of normal life. Yet the best-known are big ticket affairs – Glastonbury cost £210 plus £5 booking fee this year – that possess powerful economies of scale.

The festivals business appears to have low barriers to entry and new events spring up constantly. Venues such as New York’s Radio City Music Hall and London’s Hammersmith Odeon are impossible to replicate but every farmer has a field. Many are tempted to try to rival Worthy Farm, the venue for Glastonbury since 1970.

It is harder than it looks. “There is an element of Darwinism in the festival business,” says John Reid, head of European concerts for Live Nation, a US music promoter. Most large festivals have operated for a long time, or were started by deep-pocketed promoters: Latitude was founded in 2006 by Melvin Benn, the managing director of Festival Republic, which manages events including Reading and Leeds.

There are many independent festivals but they take their chances on the weather and ticket sales, with little to fall back on if things go wrong. All Tomorrow’s Parties, one promoter, this month cancelled its Jabberwocky event in London at the last minute due to low take-up, causing acrimony. “If we had gone ahead, it would have been the end of ATP,” it declared.

Even a well-known name can fail. Vince Power, Mr Benn’s former partner in Festival Republic, which was founded as Mean Fiddler, was this month banned by a judge from staging live music events because he had not paid for the required licences for his Hop Farm Music Festival. Mr Power’s Music Festivals Group went into administration in 2012 amid financial problems.

The financial challenge of festivals is that they are one-off events, with all of the infrastructure and stages having to be erected temporarily. A permanent venue can amortise its capital investment over 25 years; a festival has only a few days.

As a result, they need to sell a high proportion of tickets – 85 per cent or more – to earn a profit. Those that achieve it gain additional money from sponsors, making successful, well-run festivals highly profitable. Reading and Leeds was this year attended by 200,000 people, compared with just 8,000 at Reading in 1989, and its annual turnover is between £40m and £50m.

The entry ticket is only part of the cost for attendees – they either have to camp or pay a provider to erect a tent or tepee for them. Once inside, they will pay a premium for food and drink. The average UK “music tourist” spent £396 ($650) on attending festivals in 2012, compared with £87 at concert venues, according to UK Music, a trade group.

Festivals have thus become big business, while gaining much of their appeal from being a respite from the pressures of the capitalist world. “People who can afford tickets tend to be working very hard, whether for employers or at school. They are an incredible blowout from pressured lives,” Mr Benn says.

Burning Man is not a commercial event, despite the wealth of some of its attendees. It forbids payment for goods and services, and is based on free displays and gift-giving. “We’ve given you all a chance to live like artists out here . . . Give it all away, live on the edge of survival,” Larry Harvey, one of its founders, told the “Burners” in 1998.

It is at the extreme end of festivals’ counter-cultural ethos but many have a communitarian spirit and it is common to attend in groups rather than as individuals. A study of young people at Reading and the Big Chill festival by Bath university psychologists found that many of them were seeking the emotional experience of “collectivity and belonging” there.

In one sense, this is an illusion. Festivals are not actually alternative worlds, they are an entertainment feature of the existing one. They are release valves, not revolutions. In his more ambitious moments, Mr Harvey calls upon those at Burning Man to take its lessons home and to live their lives differently. In practice, most carry on as usual.

The same applies to those at more conventional festivals. They know that the event is safe, well-organised and entertaining because they and the sponsors have invested a lot in making it so. They realise it will last a few days and life will then resume. But it does not bother them because they are having fun.

Twitter: @johngapper

Comments