The joys and perils of artistic collaborations

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Artists aren’t exactly known for their accommodating, easy-going ways. More often, it’s words such as “egocentric” and “introverted” that spring to mind.

In reality, though, few artists work in total isolation, especially once they have achieved a certain level of success. The likes of Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst have teams of assistants making their work – yet these people, never namechecked, can hardly be called collaborators. At the other end of the fame scale, collaboration is crucial for so-called “emerging” artists, both in terms of sharing materials and work spaces, and exchanging ideas. As a group, it’s also easier to capture the attention of the press and public.

In 1874 Monet, Renoir, Morisot, Cézanne and others got together to put on an exhibition in Paris, calling themselves the Société Anonyme des Artistes. In a famously sneering reference to Monet’s “Impression: Sunrise”, art critic Louis Leroy’s review was headlined “The Exhibition of Impressionists”. The name stuck; the artists went on to stage seven more shows before going their separate ways.

Nowadays, art school is a crucial time for young artists to form a network of allies. Veteran collaborators Gilbert and George met in 1967 at St Martin’s School of Art in London and have worked together ever since. They dress in complementary tweeds, dine together every evening and, in interviews, talk only as “we”.

What’s interesting here is the power balance. If artists really are egomaniac non-compromisers, how do they ever work together? Contemporary art’s star twins Gert and Uwe Tobias begin their paintings by each making a piece of work, and then deciding which to develop. Tellingly, they are clear about whose idea was whose, even though no one will ever know once the work is complete.

Such complete convergence is unusual in two people, let alone two artists. German-Swiss artist and writer Dieter Roth (1930-98), however, worked together with Daniel Spoerri, Robert Filliou, Richard Hamilton, Arnulf Rainer and, later, his son Björn. His collaborations with Rainer (born 1929), a self-taught Austrian painter, printmaker and photographer, were a tussle of artistic egos, the results of which can be seen in a new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in London.

The two worked together in Rainer’s studio in Vienna, on and off between 1972 and 1983, producing some 700 works: drawings, collages, prints, films, performances and over-painted photographs. It was a partnership fuelled by creative tension – more a duel than a duet – yet the results are often light and comic. After each session, the artists would divide up the works they’d made; this show is drawn from Roth’s share and much of it has never been exhibited before.

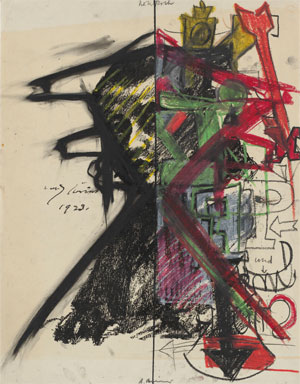

Drawing was at the centre of their practice: both were talented draughtsmen. As your eye adjusts to the drawings’ scrawls and swoops, you can make out two very different hands at work. One – Roth’s – is controlled and lyrical. The other – Rainer’s – is angry, all hard black marks. Nowhere is this clearer than in “Trennzeichnung” (“Split Drawing”) from 1975, where each takes one side of the board, a line dividing them. They referred to their creations as “Misch und Trennkunst” – mixed and separate art – “Trennzeichnung” being the latter.

The exhibition has been lovingly curated by Roth’s son Björn. Yet there is something odd about a selling show in a commercial gallery of works never intended for the art market, made by two men who shunned it. A video shows Roth and Rainer gleefully ripping up and binning reams of drawings. For them, the collaboration was about freeing themselves from the pressures of working alone, not about producing sellable art.

When working together, they insisted on an unfettered, spontaneous approach. In these drawings, prints and posters, we see two artists unchecked by the usual forces of reason and self-doubt. Like a Jackson Pollock, the energy that went into these works comes off them like heat.

Yet Roth and Rainer were serious about their endeavour: they were seeking to break out of creative safety in a kind of ceaseless experimentation. Showing me around the exhibition, Björn explains, “When artists like my father are trying to make something ugly, it always turns out beautiful. [Through collaboration] he was trying to escape from this sweetness, because he was a very sweet, melancholic man.” Ironically, there is a beauty – a perverse harmony, even – in Roth’s and Rainer’s contrasting styles. In “Schluss-Mist” (“End-Dung”) from 1975, Rainer takes a thick black crayon to Roth’s delicate abstract watercolour and somehow improves the picture, highlighting the distinct textures and suggesting depth.

By all accounts, Rainer was difficult to work with, dropping out of Vienna’s Academy of Applied Art after just one day and out of the Academy of Fine Arts after three, but he evidently had respect for Roth. “DR easily takes me by surprise repeatedly by immediately turning values upside-down, to demonstrate that the opposing view can also be made important,” he wrote.

In one series on show from the early 1980s, Rainer posted photocopied drawings to Dieter and Björn (then in his early 20s) for them to add to and send back. Dieter contributed delicate lines to Rainer’s rough scrawl and Björn added watercolour squiggles. They sent the drawings to Rainer and when Rainer returned them each one had a hole punched through its heart. “I was like ‘what is wrong with this guy?’” Björn laughs, “But now I love the holes, I don’t know why.”

One of the most famous partnershipsing ground was between Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, ageing pop artist and precocious young talent. The paintings they made between 1983 and 1985 were panned by the critics, but Warhol’s biographer Ronny Cutrone insists the relationship was mutually valuable: “It was like some crazy art-world marriage. The relationship was symbiotic. Jean-Michel thought he needed Andy’s fame, and Andy thought he needed Jean-Michel’s new blood. Jean-Michel gave Andy a rebellious image again.” Basquiat persuaded Warhol to start painting on canvas again, as he had done in the early 1960s, and Basquiat experimented with Warhol’s trademark silkscreen printing.

Collaboration isn’t, for most artists, a recipe for making masterpieces but rather a way of breaking habits – and new ground. The results are unpredictable, and sometimes very different from each artist’s “classic” work. For me, that’s part of the appeal.

Dieter Roth, Arnulf Rainer: Collaborations, Hauser & Wirth, London, until May 3. hauserwirth.com

Comments