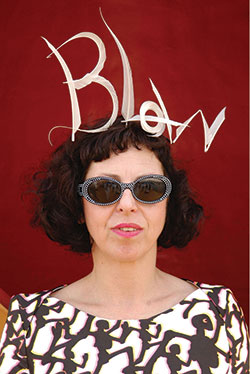

Blow for the unexpected

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I expected many things when I first heard Somerset House in London was planning the exhibition Isabella Blow: Fashion Galore, which opens next week with more than 100 pieces from the late style icon’s wardrobe.

I expected, for example, that this would inspire many odes to Isabella, from those who knew her well and not so well. And so it proved: among those weighing in were journalist Colin McDowell, novelist Andrew O’Hagan, and heiress and artist Daphne Guinness, who actually bought Isabella’s wardrobe, preserving it in perpetuity.

I expected it would serve as an opportunity to pay photographic homage to many of Blow’s most amazing looks, from an Alexander McQueen flesh-toned crocodile dress to a Jun Takahashi pink burka-like garment. And so it did, thanks to a high-concept catalogue photographed by Nick Knight, styled by Amanda Harlech, and featured everywhere from V to the Daily Mail.

What I did not expect was the stream of condemnation it has provoked about street style – the popular practice of photographing “real people” as they go about their business in “real clothes” and then posting the pictures online for all to see. For street style has made stars out of people otherwise toiling away in the fashion trenches, from Taylor Tomasi Hill, until recently creative director of the ecommerce site Moda Operandi, to Tank editor Caroline Issa, and, it appears, not everyone is happy about that.

For almost every memoir written about Blow focusing on her “eccentric style”, there has been an equivalent amount of scorn cast on those who aspire to pick up her mantle of fame through clothes. To sum up these arguments: Blow was the real thing, and today’s crew are simply pretenders. She was dressing for her own love of the art, and they are dressing for the camera, and their own brand building. She had integrity, they are fakers.

It’s a seductive argument, especially for anyone who has rolled their eyes at the ridiculousness of someone dressed up in full evening garb at 10am for what seems like the sole purpose of catching the eye of a photographer. It’s tempting to join this chorus of disapproval but isn’t it more interesting to wonder what all this is actually about?

As far as I can tell, the problem is that we no longer trust the idea of personal style. Once upon a time – in Blow’s time – someone who dressed in a highly specific way, consistently, over time (which I think is a more accurate characterisation of her style than “eccentric”, which devalues the considered way she built her look), was clearly dressing to please themselves or to define themselves. Because, otherwise, what was the pay-off? Passers-by giving you weird glances? It’s not like random looks went viral to create an insta-brand. And it’s not like what Blow wore – the corsetry, the hats, the extreme shoes – was about comfort; it was about reinvention: of the body, perception, possibility.

The reason her style is so lauded now is that it represents a kind of insider surety that we – by “we” I don’t just mean fashion professionals, I mean anyone who pays attention to what others wear, and thinks about how they themselves might be affected by it – no longer have.

…

The irony is, it’s precisely that kind of dedication to an individual look that spawned the whole idea of street style in the first place: that inspired people such as Scott Schuman (aka the Sartorialist blogger) to search for men and women with a carefully crafted way of dressing themselves, who might not – in contrast to Blow or any other fashion professional – find their way in front of a photographer’s lens in the course of their daily lives. Meaning the photographer had to go to them. Wherever they might be.

And once they did, and the discipline took off thanks to the perfect storm of fashion, reality pop culture, and technology, the brands that used to set trends took note, and started wooing the style stars. Which meant it became harder to tell what was true personal choice when it came to what Blow’s heirs wore, and what was marketing. Which undermined the entire endeavour, and led to condemnation, which led to . . . well, what we have now: the hagiography of Isabella Blow as a representative of a genuine approach to dressing that no longer seems to exist.

(Even though it does; consider US Vogue’s Lynn Yaeger, a journalist whose kewpie doll lips, Clara Bow hair and tendency to dress in layers like a matryoshka doll complement razor-sharp skills of observation.)

It’s a sad state of things, really, and it seems to me we should stop whining about what we can’t know, and have a little confidence in our own powers of perception. Indeed, Blow herself would be horrified, because if there is one lesson that should be drawn from her wardrobe, it is about the pure joy that can be found in great clothes; the fun and self-expression and safety blanket that is the art of dress. Wear it and weep.

——————————————-

More columns at ft.com/friedman

Comments