A look at the ancient roots of the olive tree, from Adam to Zeus

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A few weeks ago a business trip took me to the large, modern and mechanised packing barn of a commercial plant nursery near Eindhoven in the Netherlands. Inside the barn, six-metre-high trees and voluminous shrubs were being manoeuvred by forklift, their root balls machine-wrapped in hessian and top growth neatly bound with twine before being lifted to the backs of waiting trucks. Amid the automated ballet of high-tech machines, a gnarled, contorted olive tree sat in one corner of the barn, its root system encased in a hefty timber box at least a metre tall and four-metres square. “That,” declared the nursery manager, “is 1,000 years old – probably more.”

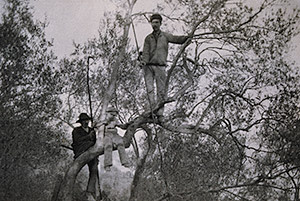

The use of mature trees and shrubs in garden and landscape design is nothing new. Capability Brown shifted mature trees on the estates he worked on, while John Jacob Astor built an extension to the local railway line to his estate at Hever Castle in Kent, southeast England, to bring in mature trees transplanted from Ashdown Forest. In general, though, commercially grown mature trees are rarely more than 50 years old; above that age the logistics of shipping large, heavy plants make it financially unviable. Yet the idea of 1,000 years or more of history, boxed up in a modern warehouse, is a very different proposition to a commercially grown nursery tree that has always been destined to be shifted and planted.

The wild olive (Olea europaea) has been around for at least 50,000 years, and there are groves of wild trees from Anatolia through the Aegean and Mediterranean. The Roman agricultural writer and theorist Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (AD4-c.AD70) described the olive tree as “Olea prima omnium arborum est” (the olive is the first of all trees) in his agricultural treatise De Re Rustica. By the time of his observation, the olive had been in commercial cultivation for several thousand years. Archaeologists have excavated olive pits at sites that are 8,000 years old. The first evidence of olive oil production was found at a 6,000-year-old site at Carmel in Israel.

The exact origins of the domesticated olive, which has noticeably larger and juicier fruit than its wild ancestors, has long been the source of scientific debate. The general consensus for many years was that they were probably first cultivated in the Levant region. Recent analysis by the National Centre for Scientific Research in France has narrowed the origins even further.

The research team took samples from 1,263 wild olives and 534 cultivated plants from across the Mediterranean, and studied the genetic material from the chloroplast (the structures where photosynthesis happens). Chloroplast DNA is passed on to descendent trees, so the team were able to track variations in the lineage of trees, pinning down the change from the bitter, small and hard wild olive fruit to larger oil-rich olives to Anatolia and the borderland between Turkey and Syria. From there, domesticated olive varieties were developed further in three key geographical areas – either side of the Strait of Gibraltar, the near east and the area around the Aegean.

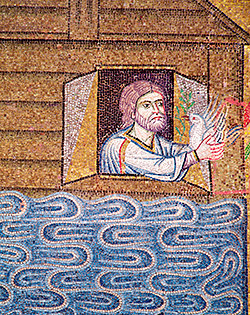

The economic and cultural importance of olives has ensured that the mythology surrounding the tree is deep, varied and entirely without regard for social or religious boundaries. The olive was one of three trees (the others being the cypress and cedar) that sprang from seeds from the Tree of Knowledge sown by Adam’s son. An olive branch in the beak of a dove marked the end of the biblical flood, and has for centuries been a symbol of peace.

There are depictions of olive oil production in ancient Egyptian art, and a tool for pressing oil found among grave goods. Tutankhamun wore a crown woven with olive leaves, and Ramses III presented olive branches to Ra, the sun god, as a symbol of enlightenment.

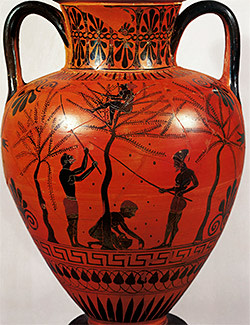

The olive reached its mythological zenith during the time of the ancient Greeks. Zeus offered Athena the guardianship of the city of Atikka in return for the gift of a grafted olive tree, which he deemed more valuable than Poseidon’s offering of a powerful war horse.

Athena’s tree was reputedly planted in the Acropolis but was burnt to the ground during the Persian invasion of 480BC. The blackened tree was abandoned to the smouldering ruins but began to produce new shoots, from which, legend has it, every olive in Greece is propagated. Such a high value was placed on the olive that the Constitution of Athens was amended during the time of Solon (638BC-558BC) to include a law covering the cutting of olive trees. Regardless of whether the tree was on public land or in private ownership, a guilty verdict meant the death penalty for the culprit.

As much as Solon’s law was recognition of the religious and cultural significance of the olive tree, it would have surely been aimed also at protecting the economic advantage gained from a vibrant olive oil industry. The Cretans and Phoenicians were the great oil salesmen of their day, trading throughout the Mediterranean. By the time of the Romans, olive oil production was codified and classified into 10 different grades. As ever, the slaves had the worst of it – their oil, known as “cibbarim”, was made from diseased fruit.

Olives became global plants from the mid-1600s, firstly as introductions to Latin America, then from the late 18th century to California, China and Japan.

The appreciation of the olive as an ornamental plant is more recent. Its silvery grey foliage is handsome but unremarkable – though it can be cut to a variety of topiary shapes. Flowers are inconspicuous, fruit never guaranteed in cooler climes. Drought tolerance makes them suitable for locations where heat and light exposure pose problems, such as roof terraces. Smaller plants can be arranged and clipped into hedges, creating a drought-proof alternative to buxus.

The real interest and aesthetic value lies, however, in the trunks of old trees. The combination of a hard life and repeated pruning (aimed at maintaining a manageable crown for easier harvesting) results in trunks that are squat, contorted and fissured, their history worn in craggy glory. There are notable examples throughout the Mediterranean and beyond.

Outside the church of Santo Domingo in the medieval town of Pollensa, Mallorca, is a tree that seems to be clinging on to life by divine providence alone. The canopy is thin and wispy but the trunk is vast and squat, the top part of the stem having decided at some point to grow around itself, like a giant timber scarf.

Even as far north as Britain there are elderly olives to be admired. The largest is at Chelsea Physic Garden on the Embankment in London. Great uncertainty exists over the age of this tree (it is certainly more than 100 years old) but, remarkably, it often produces viable fruit in the comparatively balmy microclimate of the garden. Enough, in a good year, to make one whole jam jar full of oil.

The large, aged olive trees that can now be obtained at nurseries and garden centres are often a consequence of commercial imperative. As soon as the productivity of an individual tree declines, its number is up. In the past, trees would often be cut down and burnt but now the emergence of a market hungry for old trees with character has offered them a reprieve. A naturally shallow root system makes them relatively easy to lift and transport too. So a tree born on a Greek hillside in the years before the Battle of Hastings could conceivably end its days actually in Hastings.

Matthew Wilson is managing director of Clifton Nurseries in London

Images: Bridgeman; Corbis

Comments