Lunch with the FT: Shane Smith

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Lunch with the FT is a simple format: eat, drink, talk and the FT pays the bill. When I explain this to Shane Smith, hard-partying co-founder and chief executive of Vice Media, his response lifts the spirits on a gloomy winter’s day in southern California.

“That’s great, because I like food and I like booze,” he says, differentiating himself from acolytes of the alcohol-free lunch. This depressing trend is prevalent in health-conscious Los Angeles. But Smith, in town to meet business partners at Google, is already well into the first of many glasses of rosé when I arrive.

We have arranged to meet at Gjelina in Venice Beach, near Google’s new media production studio. The restaurant specialises in tapas-style dishes and is popular with the skinny jeans-wearing media and fashion set that has taken over Venice, once America’s best-known enclave of hippies, bodybuilders and oddballs. Smith, waiting at an outdoor table under a gunmetal sky, knows all about this fashion-conscious crowd, as co-founder and former editor of self-proclaimed “hipster bible” Vice magazine.

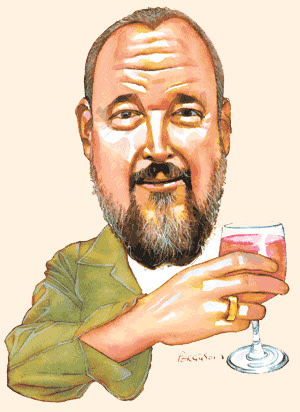

A big, bearded bear of a man, with closely cropped hair and a chunky gold ring on his finger in the shape of the Vice logo, the 43-year-old Canadian says he “can’t fit into skinny jeans”. And, as a father of two, he admits he no longer has much time for the hedonistic life extolled in the magazine. These days his interests are different. “The news stuff,” he says. “That’s what’s driving me.”

Today Vice, which started in 1994 in Montreal as a niche music magazine, is an international brand with 800 employees in 34 countries, several online video channels, and an advertising agency with clients that include Vodafone and Nike. The print magazine has 1m readers globally and, according to company projections, revenues are set to exceed $200m. Next year it will launch Vice, an HBO news magazine TV show aimed at young people, and an online news network in 18 different countries, which will blend live programming with documentaries.

Vice’s documentaries have a growing reputation; Heavy Metal in Baghdad (2007), which followed a hard rock band during the Iraq war, won awards on the film festival circuit while this year’s Reincarnated earned acclaim for its depiction of the rapper Snoop Dogg’s embrace of Rastafarianism.

Smith himself has fronted several films for Vice and achieved notoriety in 2008 when he and a colleague secretly shot The Vice Guide To North Korea. The film is notable not only for its on-the-ground perspective of a country rarely captured in news reports, but also for Smith’s howling rendition of the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK” in front of his bemused North Korean handlers in a karaoke bar.

…

I elect to join him with a glass of rosé, and we order our food. I have barely looked at the menu but scan it quickly while Smith rattles off some dishes for us to share: red butter lettuce salad, rapini, pork meatballs. “What’s your favourite thing?” he asks the waitress.

“The duck,” she says. “And the nettle fettuccine.” I think: nettle fettucine? Well, we are in Venice, after all. We take her recommendations; I also order the trout salad and red wine venison sausage.

I ask how Smith, raised in Ottawa, the son of a computer programmer father and paralegal mother, got into journalism, and crafted an approach to video reporting somewhere between Hunter S Thompson and the globetrotting Brit Alan Whicker.

As a teenager, he says, he was heavily into punk – inspired not only by the Clash and the Sex Pistols but by contemporary US groups such as the Dead Kennedys – and a hard-living subculture; several peers died of drug overdoses and he admits to having a fairly fatalistic outlook during this period. “When you’re 18, 19, you want to live fast and leave a beautiful corpse behind. It’s kind of romantic, whereas now I’m a f***ing hypochondriac. But at the time I thought I was going to die anyway so I might as well go out there and suck the marrow from the bone of life.”

He began writing in the early 1990s, having left Canada to travel in Europe. “I thought I was a pretty good writer but I didn’t have anything to write about. I wanted to go out in the world, have some adventures and then write about them.”

He headed to Yugoslavia, where war had broken out. “There was a lot of ecstasy-taking going on, a lot of shooting machine guns off to see the tracers. I was 19 and it was all very exciting.” He moved to Hungary, freelancing for the Budapest Sun and Reuters, and carved a lucrative, yet precarious, sideline as a currency hedger. “Real cowboy capitalism. I was hanging out with lots of seedy dudes. I had a car and driver and lived in the same building as the Hungarian prime minister. But I couldn’t take any of the money out of the country.”

Returning to Canada, he founded Vice magazine with two friends, Suroosh Alvi and Gavin McInnes (Smith and Alvi still control the company; McInnes left in 2008 citing “creative differences”). In 2001 the magazine relocated to Brooklyn where, recognising it wasn’t ever going to be a mass-market title, it set about finding niche readers around the world. “We decided to go after our demographic – the cool kids in London or Berlin or Stockholm – and get to scale that way.”

…

Our waitress returns with meatballs and rapini and we order a bottle of rosé. Smith spoons some of the rapini on to his plate. Very healthy, I say. “I’m as unhealthy as they come,” he replies. “I just like bitter greens. And meatballs.”

Video proved to be a significant milestone in Vice’s evolution. It formed the basis of a relationship with Tom Freston, former chief executive of Viacom (the company that owns Paramount Pictures and MTV). In 2007, Vice and Freston, who knew something about youth brands having been head of marketing at MTV in its 1980s heyday, struck a joint venture deal to create VBS, an online video network. (Vice later bought back the Viacom stake – Smith won’t say how much for, only that it was “a lot”.)

Inspired by Smith’s friend the film director Spike Jonze, Vice concentrated on increasing its video output. The push won a new audience – the youngsters marketing executives refer to sometimes as “millennials” – and new advertisers. “We went from a Gen X company as an indie mag to a Gen Y company online,” says Smith. “Gen Y consume most of their media online and mobile. Gen Y, as the baby boomers drop off, are the largest cohort with the largest amount of money – despite the fact that half of them are unemployed.”

We talk about the forthcoming HBO show. Smith is convinced that Vice’s hipster viewers and readers also want news. “People want to wake up,” he says. “I was just in Afghanistan and we were working on a piece [for the show] on child suicide bombers. They’re recruited by the Taliban to be suicide bombers, they’re told that they won’t die, that their families will get money. The kids are 11, 12 years old. I saw them and I lost it …. .” His eyes fill with tears. “Sorry,” he says.

He says his wife is “incredibly supportive” about him jetting off to warzones. “She knows I’m careful,” he says, munching on a stalk of rapini. The only trip he ever shelved was a film on the Somali pirate stock exchange. “Poor people in Somalia can invest small amounts of money towards buying a rocket-propelled grenade or a machine gun and if it’s successful in a hijacking [they] get a dividend. It was a great story. We had these pirates who …were going to take us around.

“Two days before we got there, CNN figured out the same dodge. Then some other pirates found out about it and said, ‘You’re f***ing our whole s**t up.’ So they started shooting at the pirates that we were going to use and there was a big firefight in Puntland [in northeast Somalia]. So I’m like, ‘OK, I’m not doing that.’ ”

Despite such setbacks, the gonzo approach seems to work for him, I say. Smith disagrees with my description of his journalistic style, though he admits to being a fan of Hunter Thompson – “the first present my dad ever got me was a signed first edition copy of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas”. “Everyone calls Vice ‘gonzo’ but I don’t think we are,” he says. “I call it ‘immersionism’. We immerse ourselves and press ‘record.’ ”

Brands have been eager to associate themselves with this content – in one recent video a Vice correspondent took LSD at the Westminster Dog Show, the US equivalent of Crufts – and Smith has encouraged their interest. Does corporate sponsorship fit with Vice’s edgy ethos? “They have given me money to create one of the most forward-thinking channels we’ve ever done,” he says, referring to the Creators Project, an online channel underwritten by Intel that supports artists who use technology to “push the boundaries of creative expression”.

I’ve been eating the duck but we swap plates and I take his fettuccine: our bottle of wine is finished and we order another.

Vice’s moves have intrigued others too. Last year Tom Freston, with WPP, the marketing conglomerate led by Sir Martin Sorrell, and the Raine Group, a boutique bank, bought a small stake in the company. More recently, it has assembled from outside investors a “war chest” – again, Smith won’t disclose how much – to buy media brands struggling in the digital landscape. The first deal came this month, when it bought the UK style magazine, iD – one of several that influenced Vice magazine in its early days.

All the while, says Smith, companies interested in Vice continue to circle. “News Corp, Time Warner, Bertelsmann, Condé Nast …everyone is after us.” One of the company’s fans is Rupert Murdoch, who recently tweeted after meeting Smith and his colleagues: “Who’s heard of Vice Media? Wild, interesting effort to interest millennials who don’t read or watch established media. Global success.”

“Rupert came out and hung out in the office,” says Smith. “It was funny. We took him to a bar in Williamsburg and we got him drunk on tequila; and then everyone started tweeting and freaking out, blogs saying: ‘Is News Corp buying Vice?’ He’s a sweet old guy.I don’t agree with Roger Ailes and Fox News but you have to give Rupert his due. The guy is a shark.”

Um, you mean in a good way? I say. “Yeah. He’s a murderer – in a good way. In Jamaica that’s what they say – ‘He’s a murderer!’ when they’re giving someone a compliment. “I respect Rupert’s legacy – he took the second largest newspaper in Adelaide and turned it into one of the world’s biggest media companies. You have to eat that sausage,” he says, pushing the plate towards me. “I’ve had my quotient.”

Would he ever sell up? He shakes his head. “There are only two companies in the world that can help me.” He sips his wine. “That’s Facebook and Google because they are going to make me the largest digital network in the world, which is my goal. I don’t know how News Corp would help me. I know why I’m sexy to them, which is what I said to Rupert. ‘I have Gen Y, I have social [media], I have online video. You have none of that. I have the future, you have the past.’ ”

After another glass, our second bottle of wine is depleted and I order a double espresso in a vain attempt to sober up. Has this very 21st-century party animal turned digital media mogul really mellowed with age, I ask?

Smith begins a riff about his hedonistic days. “I would be at the party and would just want to get wasted, take coke and have sex with girls in the bathroom,” he says, with a sigh. “Now …sometimes I just want to have a nap.”

Matthew Garrahan is the FT’s Los Angeles correspondent

——————————————-

Gjelina

1429 Abbot Kinney Blvd, Venice Beach, California

Smoked trout $13.00

Lettuce salad $10.00

Rapini (broccoli rabe) $8.00

Meatballs $13.00

Romanesco salad $8.00

Venison sausage $15.00

Nettle fettuccine $17.00

Duck confit $22.00

Glass of Pampelonnerosé x4 $56.00

Bottle of Pampelonne rosé x2 $112.00

Bottle of mineral water $7.00

Double espresso $4.00

Total (inc. tax & service)$369.94

Comments