Burgundy 2012 wines

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

If you cut through one of Nicolas Potel’s veins, it would probably bleed red burgundy. His father, Gérard, died young, in 1997 – and the family’s Domaine de la Pousse d’Or in Volnay is now in the hands of a Swiss owner, leaving Nicolas to make his way with what was initially an eponymous négociant business and is now a mixture of his own vineyards and bought-in wines under the respective names Domaine de Bellene and Maison Roche de Bellene. The latter business depends on calling in wines and favours from vine growers the length of the Côte d’Or, people with whom he grew up, so he is particularly well plugged in to the nuances of the fortunes of the blessed “golden slope” that is responsible for all of the world’s great burgundy.

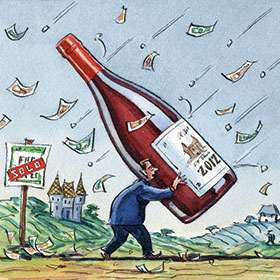

I taste with him every year and, last December, over dozens of his 2012s, he described a completely novel situation: “My father said it would happen but it’s still a bit destabilising – all this money to buy land coming from outside Burgundy. There have been really big movements in the price of land, which is now completely stupid. It’s become simply too expensive to buy it to make wine or to buy land from the rest of the family.” This is perhaps a little rich, since his backers are Asian as well as French, but it reflects the common structure of most domaines, or small wine farms, in Burgundy, whereby they are run by one or two family members but have to pay an annual dividend to many other family shareholders.

As land prices soar – one ouvrée, 428 sq m, sold for €2.4m recently – largely thanks to investment from Bordeaux, the US and Asia, many non-winemaking sisters and brothers of vignerons have been keen to sell their shares in their family domaines. But young vignerons are loath or unable to borrow the finance for such an acquisition themselves. Burgundian farmers may be castigated by their customers for treating themselves to smart German cars for Sunday best but most of them spend their days in the vineyard. These are essentially farmers, with a long tradition of caution. Extremely high prices would be needed just to pay the interest.

This is not Bordeaux, where few of the better-known producers prune their own vines. They act en masse each year, goaded by a well-structured marketplace and many an intermediary, and where we have seen such ambitious swings, usually upwards, in prices over the past few decades. Burgundian growers tend to sell on a handshake direct to their buyers – and in very, very much smaller quantities.

This is the background to the 2012 vintage in Burgundy, the second of three small crops in four years and the result of a growing season that was the most challenging that today’s vignerons could remember (frost, hail, storms, rain, sunburn, mildew and, in some cases, rot). On the Côte de Beaune, in the south, yields were disastrously low, thanks to particularly vicious hailstorms – so much so that I hesitated to make appointments at some particularly badly hit addresses. I was greeted chez Lafarge in Volnay, for example, with the rueful observation that, most unusually, all visitors were on time during the 2013 autumn tasting season because there was so little to taste. So few grapes were harvested from some plots that growers have made notably fewer separate cuvées than usual.

“I’ve never seen such severe hailstorms – and they struck two years in a row in the same area,” said Frédéric Lafarge, whose vineyards were stripped by hail both at the end of June and the beginning of August 2012. He made barely 20 per cent of a normal crop. Some growers were insured but you can insure only for a set sum, and no one could afford to insure against the full financial impact of crop loss at today’s prices. Hail tends to come from the south, so the Côte de Beaune is generally much worse affected than the Côte de Nuits. Hail incidence seems to be increasing and there is now serious talk on the Côte de Beaune of instigating a network of cannon that will seed hail-bearing clouds at a cost of just €20 a hectare.

After my week of tasting in Burgundy, I got the train from Dijon to Paris for the weekend and kept bumping into wine people there badmouthing Burgundians for the price rises being imposed for the 2012s. But I can see why growers have put up their prices – and am not surprised to learn that négociants, the bigger merchants, are now paying such high prices that many growers are choosing to sell early to them rather than bottle wine themselves. Indeed, competition for good 2013s is so fierce that the smaller négociants, the likes of Nicolas Potel and Oliver Bernstein, have been finding it hard to stay in the game. As Olivier Bernstein, who has built up a remarkably successful business since 2007 for his robust, rich wines from a standing start as a grower in Roussillon, admits: “It has become more difficult to maintain our sources than to sell our wine. I’m helped because they see me more as a fellow vigneron than a négociant, but I have to take care to understand their problems and personalities, and to be sure to dine with them three times a year or so.”

The 2012s are currently being offered to British (and Asian) wine lovers by a host of UK-based wine merchants. In general, they are delightful wines – at least they are delightful to taste now. I will be offering more specific opinion next week. Because the Grands Crus are available in such tiny quantities, they tend to be at stratospheric, and sometimes not generally published, prices which lead cynics like me to wonder just how the profit is being shared between growers and merchants. But burgundy lovers, who are so numerous today alas, can console themselves with the thought that there are many beautifully made wines much lower down the status ladder. They may cost more than the 2011s but are almost certainly more delicious.

——————————————-

See JancisRobinson.com for well over 1,000 tasting notes on 2012 burgundies.

Bid for a table for six guests to join Jancis Robinson at our Charity Dinner at Christie’s, London, on Tuesday January 28 and help raise money for the FT’s seasonal appeal charity World Child Cancer. For more information go to www.christies.com/ftappeal

——————————————-

Advice for 2012 burgundy lovers

● Avoid Grands Crus. Competition is just too great for the 2012s.

● Forgive Volnay. Pommard prices Hail stopped play or at least shrank total quantities available.

● Don’t be a négociant snob. The grower v merchant playing field is more level than ever and the majority of négociant businesses are every bit as motivated by quality as the small growers. They may also have better equipment and more cash to make quality-oriented decisions.

● Look for older vintages. There is often better value in burgundies with a bit of bottle age that were made before prices zoomed up.

Joseph Drouhin, Beaune Grèves 2012. According to Véronique Drouhin, responsible for this, one of many delicious Beaunes, 2012 was the smallest crop for 15 years in Burgundy.

Comments