The ‘bivalve bishop’ of Grand Central on his love of oysters

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Ask Sandy Ingber, executive chef of the famed Oyster Bar in New York’s Grand Central Terminal, to recount his most memorable experience at the restaurant and he doesn’t hesitate: “It was a Saturday night, in the summer. There was a flash fire from one of our refrigerators. It was a five-alarm fire – it nearly burnt the terminal down.”

The year was 1997. Ingber had joined the restaurant as a fish buyer in 1990, but had been made chef only earlier that year. He recalls: “The manager who called me said, ‘I want you to know, you still have a job, and that Mr Brody [Jerome Brody, who bought the restaurant in 1973 and made it world-famous] said we’ll close for only two weeks. We will be back after that to open our doors, even if we just serve cold food during the renovation. We’re going to let customers walk through here to let them see how hard we’re working to bring it back’.

“And that’s just what we did. For four months, we served cold food only, while they did the renovation to the rest. That’s something I’ll never forget.”

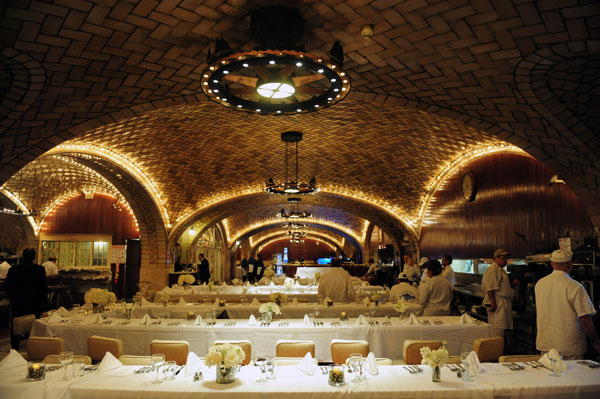

The Oyster Bar – like the Beaux Arts masterpiece in which it is housed – celebrated its centenary this year. With its vaulted ceiling of gleaming cream tiles, it manages a rare double act by being both a New York institution and a truly wonderful place to eat.

This is fitting, since New York’s history has long been entwined with that of the Ostreidae family of molluscs. As Mark Kurlansky recounts in The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, the estuary of the lower Hudson River had 350 square miles of oyster beds in the 18th century: the native Lenape people and the European arrivals all ate the shellfish with gusto. By the end of the 19th century, those beds were producing 700m oysters a year.

At the same time the city’s waters were growing ever more polluted: in 1927 New York’s last oyster beds closed. Oysters are being returned to local waterways by groups such as the Oyster Restoration Research Project, which aims not to raise oysters for food but to allow them to filter and naturally clean the city’s bays and estuaries.

Even if oysters don’t come straight from the Hudson, New Yorkers’ appetite for them has never dimmed. Ingber rises at 3am each morning and heads for Fulton Fish Market in the Bronx to select that day’s catch. He spends $60,000 to $70,000 each week on fresh seafood – the Oyster Bar is New York’s biggest seafood restaurant – rising to nearly $100,000 a week as winter, its busiest season, closes in.

It wasn’t always this much of a success story: when the late Jerome Brody took over the venue in the early 1970s, it was, like many businesses in the city at that time, long past its glory days. It was bankrupt and derelict; the famous ceiling tiles were encrusted with filth. Brody had operated some of New York’s legendary restaurants – including The Four Seasons and The Rainbow Room – and began the process of returning the Oyster Bar to its “destination” status.

“We’re not the fanciest, but we like to think of ourselves as the freshest,” says Ingber. “We let the fish really stand on the plate by itself.” It’s mostly fish that he buys from the market; 80 per cent of the shellfish served by the restaurant comes direct from oyster farms all across the country. There are usually 30 varieties available on any given day, and their names – Chincoteague from Virginia, Pearl Point from Washington State, Damariscotta from Maine – are pinned up above the Oyster Bar’s dining counters.

Every variety served in the restaurant – more than 200 – is listed at the front of Ingber’s book, published for the restaurant’s centenary: The Grand Central Oyster Bar and Restaurant Cookbook. Now that oysters are farmed all over the country, the “R” in the month rule doesn’t apply and air freight means that oysters from Washington State can reach Manhattan as quickly as oysters from Long Island.

Oysters are firmly back in style in New York. “There’s a mystique about eating oysters,” says Ingber, “and they’re becoming more and more and more popular, especially over the past 10 years.” Fashionable oyster bars have popped up all over the city, and Ingber is glad of the competition. “Good for business,” he says.

Often nicknamed “the Bishop of Bivalves” for his deep knowledge of oysters, Ingber had never tasted one until he went to culinary school: he was raised in a kosher home where both eating shellfish and pork were forbidden.

Now he finds it hard to choose a favourite from the Oyster Bar’s menu – but when I press him, he suggests something old and something new. “I love the oyster pan-roast. It’s just a classic.” In this dish, oysters (or clams, or any combination of seafood) are swiftly cooked in cream, butter, paprika and their own juices, and served over toast – a century-old recipe that needs no adjustment.

The Oyster Bar’s modern creations are equally delightful. Ingber confesses a soft spot for the fish tacos he has developed. “Most of the time people fry the fish for tacos – but I don’t like that. We use mahi-mahi, marinated and broiled.”

Pan-roasts and polished tiles make the Oyster Bar historic; fish tacos, Bloody Mary oyster shooters and the use of sustainable seafood will help to ensure its future. “We were proud to celebrate our centenary this year,” says Ingber. “Hopefully, we’ll keep going for another 100 years.”

‘The Grand Central Oyster Bar & Restaurant Cookbook’ by Sandy Ingber with Roy Finamore is published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang ($35/£21.99)

Comments