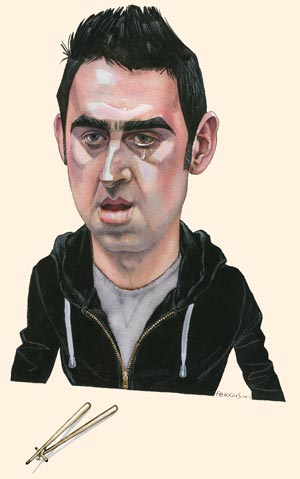

Lunch with the FT: Ronnie O’Sullivan

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Lunch with one of the world’s most talented and complicated sportsmen is at Roka, a sleek Japanese-fusion restaurant packed with chattering expense-account lunchers in London’s Canary Wharf. Ronnie O’Sullivan, current and five-time world snooker champion, has eaten here a couple of times before. “It’s a local for me and the food’s really nice,” the 37-year-old explains in a softly spoken Essex accent. He peers with interest at a dish with an open-shell tiger prawn that is being carried to a nearby table.

O’Sullivan, nicknamed “Rocket” for the exhilarating speed at which he can clear the balls on a snooker table, is for many the most talented player in the game’s history. Who else could win, as he did in May, its most prestigious tournament, the world championship in Sheffield, despite not having played professional snooker for the previous 12 months? Imagine Roger Federer taking a year off then popping back to win Wimbledon.

Like many, I am a casual snooker follower but a big Ronnie fan: he is the game’s last big draw, a throwback to the characterful days when it attracted as many as 18m television viewers to watch players like Alex “Hurricane” Higgins and Jimmy “the Whirlwind” White. But I approach our lunch with caution. My guest has a well-deserved reputation for controversy. At times he has seemed to hate the game he has been fated to play so superlatively.

In the week we meet, another fuss: O’Sullivan has suggested match-fixing in snooker could be widespread before retracting his comments a couple of days later. “Everyone knows with me,” he said semi-apologetically after winning the World Championship final, “I’m up and down like a whore’s drawers.”

Today, he is open and easy-going, more relaxed than his turbulent temperament might suggest. He orders our food as speedily as he plays. “Prawns, already peeled, you know that one?” he asks the waiter, before turning to me. “We liked the look of them, didn’t we. What else do you like? Meat, fish?” Anything, I say, as long as there’s no pineapple.

“OK,” he tells the waiter, “we’ll just go for a nice bit of seafood, some cod, cod’s nice here. Black cod, innit? Shall we go for that? Do you like rice?” O’Sullivan’s mother is Italian by way of Birmingham and I detect a little of this in his solicitous concern for my welfare at the table. “And if you’re still hungry,” he says, “we’ll order some more.”

Wine is refused; he’ll have green tea. He isn’t teetotal but has had problems with booze and drugs in the past. In his new memoir, Running, named after the obsessive activity that has helped him overcome his old addictions, he is frank about having attended Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. He even confesses to falling off the wagon for a few days a year when he allows himself to “blast it”.

“Well,” he says with a wry smile, when I ask what “blast it” means, “if there’s 365 days in the year I allow myself the odd binge. That might last one day, two days, three days, and I just get it out my system.” And that’s OK, he can manage that? “Well, you shouldn’t really. I’ve just got this mentality that I won’t put no boundaries on what I do. I just know that if I run, there’s a good chance I won’t burn the candle at both ends.”

He first began running about a decade ago – proper cross-country running, clumping through muddy tracks in Epping Forest for seven or eight miles with club runners. He does about 30 miles a week. Although he claims to be a stone or so overweight, he looks in good shape in slim jeans and black hooded top.

“Oh mate, I love my grub, I always have done,” he says as the waitress arrives with two plates of dumplings, one beef, ginger and sesame, the other lobster and black cod with chilli. “My mum’s from a Sicilian background so all I’d do was eat pasta, pasta, pasta and my mum’s family are all fucking huge.” He chopsticks a dumpling into his mouth. “So, yeah,” mouth chewing, “I really need to look at that, otherwise I’ll end up like Porky the Pig.”

I try to leave the last lobster dumpling for him but he insists: “Go on, have it, there’s loads more coming.”

…

He grew up and still lives in Chigwell, an affluent suburb northeast of Canary Wharf. As a boy he worshipped the Scottish seven-time World Champion Stephen Hendry. His father had a special snooker room built for him at the bottom of the garden. It was clear he was a prodigy: he scored his first century at 10; at 15, he became the youngest to score a maximum 147 break; at 17, the youngest to win a ranking tournament. Keith Richards, an acquaintance through O’Sullivan’s friendship with fellow Rolling Stone Ron Wood, called him “the Mozart of snooker”.

O’Sullivan laughs at the description. At school, soon after scoring his first century break, he saw the film Amadeus, a portrait of Mozart as a bratty, potty-mouthed maestro. “Best film I’d ever seen. I looked at Mozart and I didn’t see nothing abnormal about him. I thought he was just expressing himself.”

Yet he professes bemusement when people describe him as a prodigy. “I don’t see myself as talented,” he says. “I was never the most talented but I worked very hard.” I express incredulity. This is a player who at the 1997 World Championship scored snooker’s maximum break of 147 in a shade over five minutes, the fastest on record.

He agrees that there have been times he has thought: “Wow. I’ve been playing shots that none of them can play. And I know that, by playing that shot, I know that they know that no one else can play that shot. Do you know what I mean? And I get a buzz out of that.”

Two bowls of rice arrive, alongside a plate containing a large tiger prawn, split into chunks, cooked with yuzukosho seasoning. He tries a bit. “Fucking lovely,” he says, with earthy accuracy.

O’Sullivan’s Achilles heel is his perfectionism. Sublime passages of play have been accompanied by breakdowns, like the time in 2006 when he abandoned a televised match against Hendry mid-game out of despair at his own play.

“It’s possible to play the game perfectly,” he says, chopsticks darting at his bowl. “I still believe that, I won’t ever change that, because there are times when I do it – it’s the most amazing feeling I’ve ever had. It’s like I’ve worked all my life for that and I will continue to strive for it, no matter what damage it may have caused.”

He reckons his best snooker was when he was 14, 15 and 16, when he felt like a “machine”. His father drove him on, instilling in him a competitiveness that didn’t come naturally.

“I just wanted to play,” O’Sullivan remembers. “If I got beat I never got the hump, I just went, ‘Dad, can I go in the next tournament?’ And my dad would look at me, he’d punish me for having that attitude. ‘You should be hurting, you made me look stupid the other day, you lost.’” He chuckles indulgently at the memory. His father, also called Ronnie, was “a dominant alpha male, a big presence. But lovely too.”

O’Sullivan’s background was well-off but unorthodox. His parents ran sex shops in Soho. As a child he remembers hearing the thud of envelopes filled with money as they fell through the letterbox for his father. In 1992, the year he turned pro, his father was jailed for murder following a fight in a nightclub. The judge ruled it had “racial overtones”, which the younger O’Sullivan adamantly denies.

In his view the terrible crime his father committed was the result of being too willing to involve himself in other people’s problems. “He’d do anything for you, shirt off his back,” he says. “That was one of his downfalls. That’s why he ended up going where he went; he was a protector, he was like, ‘If you’re in trouble, then I’m in it with you.’”

His father served 18 years before his full release in 2010 and now lives around the corner. Had his absence spurred his son on? “It would have been easy for me to go off the rails but I remember his voice going, ‘Keep fit, keep this, keep that,’ and I had that voice in the back of my head at all times.” But he did go off the rails when his mother was also jailed, sentenced to a year for tax evasion, in 1995. “When my mum and dad …” – there is a brief pause as he searches for the word – “went away, I turned to drinking and I tried certain substances. I’d eat a lot – I was massive. And I was a mess on the [snooker] table. I wasn’t competing.”

Inconsistency has been a feature of his career. Despite his childhood brilliance it took him until 2001 to become world champion. He has missed tournaments through depression and exhaustion. In 1996 he headbutted a match official and was fined £20,000. In 2008 he made jokes about oral sex during a press conference in China, a vital new market for snooker.

Does he ever regret these “mad moments”, as he calls them? “No, none at all. They’re learning curves,” he answers. Even the headbutting incident, preceded by the official trying to make one of his friends leave the players’ lounge? “He deserved it,” O’Sullivan replies sharply, lifting himself a bit in his chair. “He deserved it. I apologised and said, ‘I’m ever so sorry,’ but I don’t go home and go ‘Awww’ and beat myself up. At the time I just thought, ‘Bollocks, I ain’t going to be treated like that.’”

A waiter materialises with a fillet of black cod wrapped in a banana leaf. “Gorgeous,” says O’Sullivan.

His latest turmoil has proved the most difficult. Three years ago he was embroiled in a legal battle over access to his children from a previous relationship, seven-year-old Lily and six-year-old Ronnie Jr. Conditions about when he could see them led him to skip tournaments, incurring the wrath of snooker’s authorities. At one point he gave up running, and was suffering panic attacks. He still suffers from insomnia. Somehow, on three hours’ sleep a night, he won the gruelling 17-day-long 2013 World Championship.

“It is a great tournament but sometimes I think, ‘Fucking hell, do I really want to go through this again?’ Sitting in your room in underpants, T-shirts, looking like a mess. Not wanting to come out because I’m scared and I’m anxious and people are going to want to talk to me, to go ‘All right, Ronnie, yeah, playing great,’ and inside I’m thinking, ‘I just want to scream.’ Do you know what I mean?”

It’s noticeable how close to the surface his emotions are. “I’ve actually cried more in the last three or four years than I have done in all the previous ones,” he says. “A lot of it is due to my children really, I love them dearly, I would never see them go without, I would support them all the way. Yet I was forced to go through a horrendous experience and fight to actually get to spend a bit of time with them.”

His voice thickens and catches, his eyes tear up. Suddenly he’s sobbing, sitting back in his chair and scrunching his white napkin into his eyes. I try to lighten the tone but fail. To my horror I appear to have morphed into the FT’s Piers Morgan.

“My fault,” he gasps, lowering the napkin. “Shouldn’t talk about it. Didn’t expect that. Thought I’d dealt with it. I’m all right, I’m all right, I’m all right. It gets you. You’ve got kids, you know what it’s like. You’d die for them” – he says it emphatically.

As he scarfs some cod and rice into his mouth with the chopsticks, our roles are reversed. That’s it, Ronnie, I find myself saying, get the cod down you, good nutritious stuff.

“Oh dear. Funny, innit?” He recovers himself. “I feel like nothing’s that important any more. I feel the rules, the clauses they put in contracts to try to pressurise you: it don’t bother me no more. I don’t care, take what you want, I’m happy. I’ve achieved everything I wanted to achieve.”

The high point was winning last year’s world championship, when his son emerged from the audience to join him at his moment of victory. “For me it was over, I had nothing to prove. I’d come through a lot of struggles to see him and then to have him there at the final, you can’t imagine how I felt then.”

A waitress refills his green tea. “Do you want some more food, ’cos you’re hungry ain’t ya?” he says to me. He asks for a menu and we order a plate of chicken with chilli, lemon and garlic soy. By the time it arrives, the Rocket has fully regained his composure. He gives me the rest of his rice. We both order puddings: lychee sorbet for me, Japanese pancakes with toffee banana for him.

With his forties approaching, he reckons he is playing some of the best snooker of his life. He credits a well-known sports psychologist, Steve Peters, with helping him overcome his mood swings. Life is looking up off the table, too. He sees his children more regularly. Earlier this year he got engaged to actress Laila Rouass. His luck is out with the pudding, though, a sweet, glutinous concoction that he abandons after a few spoonfuls. “Do you want some? Try it. Go on, have that half.” I shovel some down my mouth, habituated by now to my role as the lunch’s greedy eater.

We end with the revelation of Damien Hirst’s cooking skills. O’Sullivan has forged a close friendship with the snooker-loving artist. He also reflects that there is one “mad moment” he regrets, when he threatened to send Stephen Hendry, his main rival as snooker’s greatest player, back to “his sad little life in Scotland”. Hendry wouldn’t speak to him for several years. “That was probably the worse thing I’ve done. Because he was my hero.”

The plates are cleared away. “It was all right, weren’t it?” he says. “I’m sorry I broke down there, it’s a bit embarrassing.”

Don’t worry, I assure him. A few tears are nothing to be ashamed of. “Federer does it, don’t he?” O’Sullivan says brightly. He loves tennis; favours the industrious Nadal as much as the wizard Federer. Hard work and genius. “I hope you’ve got enough material,” he says.

www.ronnieosullivan.com launches soon. ‘Running: The Autobiography’, by Ronnie O’Sullivan, is published by Orion Books (£18.99 hardback, £9.99 eBook)

——————————————-

Roka

40 Canada Square London E14 5FW

Wild tiger prawns £18.90

Broccoli shinme £4.90

Black cod in yuzu miso £29.60

Chicken with chilli £13.90

Portobello mushrooms £5.90

Lobster and black cod dumplings £12.60

Beef, ginger and sesame dumplings £6.90

Steamed rice x2 £5.20

Dorayaki pancakes £7.90

Sorbet £2.50

Green tea x2 £6.00

Sparkling water £3.90

Total (incl service) £132.98

Comments