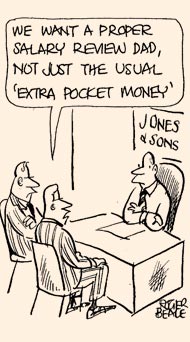

There are lessons to be learned from the family

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The study of management is underpinned by a dominant mindset – how organisations behave and what they value.

This mindset was created by business schools, spread by consulting firms and is applied by publicly quoted corporations. As a result, certain assumptions have been taken for granted: that management can be approached almost as a hard science, that people are resources to be managed with a stimulus-response pattern, that owners and managers are selfish and contentious and that the goal of any company is to maximise shareholder value. Anything that falls outside these assumptions is often ignored.

This dominant mindset has prevented us from recognising that a valuable part of the business world and even the corporate world – the family business – has been neglected.

Family businesses are viewed by most business schools as under-developed organisations, albeit with the potential to evolve into “modern” companies. Samsung, Fiat, Merck, Inditex, Koç, Tata and Cemex are obviously neither under-developed nor in the process of modernising. Conventional management wisdom gives an accurate portrayal of publicly traded companies with dispersed ownership, but it does nothing to help us understand top management decisions in family-owned businesses, businesses which comprise the vast majority of the world’s companies.

Even in the relatively new field of family business, many academics and practitioners tend to adhere to the accepted management mindset. They base their arguments on the logic of the “developed” corporate world and apply them to “under-developed” family businesses, for instance in the form of governance codes.

Business schools need to challenge assumptions and ensure that successful family business practices are also the focus of research and reflection rather than disdain. Successful family businesses cannot be understood by assuming that they strive to maximise shareholder value; or by thinking that decision-making can be only analytical.

Understanding a family business is to appreciate the value of expert intuition; to understand that individuals are not just resources, but a valued part of the business; to realise that paternalism has as much a role to play as corporate social responsibility.

Business schools need to have a better understanding of family businesses. MBA curriculums would be enriched by a broader understanding of these organisations and their management. Concepts such as honesty, pride, loyalty and long-term commitment are not necessarily naive or alien to the “real world”; indeed, they are everyday practices of successful family businesses around the world.

Management thinking and practice would also benefit substantially from a greater appreciation and understanding of family businesses. While far from perfect, family-owned companies provide insight into the quest for more virtuous – not necessarily excellent or superb– managers and organisations. Virtuous organisations – fair, prudent, courageous, moderate ones – are better at creating a common good than organisations that excel at maximising shareholder returns.

Family capitalism is built by companies that play by a different set of rules, focusing on managing assets rather than managing debt. Corporate rules are human constructions and can be changed if they do not bring about a common good. Great thinkers, including Mintzberg, Ghoshal and Abrahamson, have called for the humanisation of the corporate world and family businesses can provide worthy insight in this quest.

A humbler approach is needed. Rather than regarding family businesses merely as pupils who could use a lesson in “excellence”, business schools, consulting firms and quoted companies needs to realise that learning is a two-way street. And that there are great lessons to be learned from family businesses.

The author is director of Esade’s International Family Business Lab.

Comments