Chinese wines

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I got an email recently from a friend in France who had just lunched with the famous but reclusive Meursault producer Jean-François Coche of Coche-Dury. Could I get hold of some Chinese wine, he pleaded, because Jean-François is extremely keen to taste it. I encounter this sort of curiosity all over the wine world now because China is already the fifth-biggest producer of wine globally and yet Chinese wine is rarely seen outside its borders. Exports may be minimal at the moment but as production volumes continue to grow, it is likely that Chinese wine will increasingly find its way to palates more sophisticated than the average Chinese ones and its quality intrigues many of us wine professionals.

I’ve been visiting China about every two years since 2001 and every time I try to go to a different wine region and taste as many Chinese wines as possible recommended by trustworthy fellow wine lovers living there. I didn’t detect much qualitative progress during the first decade of this century (unlike the dramatic increase in the quantity of wine produced) but in recent years the number of entirely respectable reds has grown at an impressive rate. While in Asia last month I was asked when I thought China would produce world-class wine. I said I thought that on the basis of what I had tasted so far it would probably be within five to 10 years but added semi-facetiously, in a reference to the extraordinary speed with which the Chinese tackle their objectives, that in practice it would probably be three to six years. (This wound up as a headline in the Shanghai press that I had confidently predicted China would be producing great wine in three years.)

There is still a great deal of very ordinary, often faulty, sometimes extremely questionable liquid on sale in China labelled as wine. The blending of local ferment with wine imported in bulk is notorious and some of what is on sale is not even grape-derived. I’m constantly amazed that the Chinese don’t complain more about the thin, fruitless reds that make up the great bulk of the “Chinese wine” on offer. But what I’m interested in when I visit are the wines with real ambition.

I was very pleased, therefore, to take part in a blind tasting in Shanghai recently of 53 representatives of this group, which offered a snapshot of where China has got to. (On my first visit in 2001, only two or three examples were fielded, and pretty unimpressive they were, too.)

The first thing to say is that Chinese wine is still essentially Cabernet. It is quite remarkable that a country making so much wine offers so little diversity. This was explained later by Hao Linhai, deputy chairman of the government in Ningxia, the north-central province most liberally represented in our tasting, having provided 34 of the 53 wines, and which is most determinedly trying to become the wine province in China. He suggested that it was because wine production was originally controlled by the government that a certain groupthink prevailed. And we all know how much effort the Bordelais put in to travelling to China to promulgate the idea that the archetypal wine was red, made from Bordeaux grape varieties, preferably grown in Bordeaux. The only relief from our Cabernet and Merlot diet in the red wines was a pair of wines from a Ningxia producer specialising in a local grape speciality they call Cabernet Gernischt, which has been shown to be the old Bordeaux grape, Carmenère, now common in Chile. These wines initially gained an extra point or two for novelty value but on retasting them I found the green streak that characterises this variety just a bit too obvious.

This was especially grating since the two most common faults in Chinese wines is a lack of fruit concentration (most of the grapes are grown by farmers keen to maximise yields rather than ripeness) and the clumsy use of oak, or at least flavours designed to taste like oak. Quite a few of the wines we tasted had their fruit submerged by extremely unsophisticated, heavy, almost oily oak aromas – almost as though some sort of “oak essence” had been used. If that flavour did come from barrels, those barrels were far from the top of the tree. And since the generally high yields often result in wines with a fair amount of acidity, some winemakers seem to decide to compensate by making uncomfortably sweet reds.

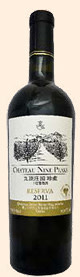

The very first red we tasted turned out to be a Château Nine Peaks Cabernet Sauvignon 2011 from a new, Luxembourg-financed, French-influenced small winery in Shandong on the humid east coast, which is far from the usual giant, marble-floored edifice that has become the norm for Chinese-owned wineries. Disconcertingly, it tasted just like a rather delicious, fully mature – far older than 2011 – right-bank bordeaux, and it somehow came as no surprise to find that the estate has links to Château Canon La Gaffelière in St-Émilion.

The wine that I thought was best of all turned out to be made by a Chinese woman called Crazy Fang on a new Ningxia estate called Kanaan. This brings to three the total of gifted female winemakers in Ningxia that I have met, the others being at Silver Heights and Helan Qingque whose Jai Be Lan won a Decanter magazine award in 2011.

The other region that provided two very decent wines was Xinjiang, with China’s biggest area of vineyard, five hours’ flight away in the far west. The climate in Xinjiang is even more continental than Ningxia’s and so the growing season is that much shorter and the wines, arguably, are a little more flamboyant and less subtle. Two of the Xinjiang producers, Zhongfei and Skyline of Gobi, are advised, like Helan Qingque, by the talented, Bordeaux-trained Chinese wine consultant and academic Li Demei.

Our tasting included nine whites (mostly – surprise, surprise – Chardonnay) and even one rosé (Cabernet Sauvignon of course) but they were generally rather ordinary. Only the Pernod-Ricard-owned Helan Mountain had harnessed their Australian winemakers to produce a white I would drink with any pleasure.

The number of good Chinese wines is definitely rising fast. This range would have been unthinkable 10 years ago. France, watch out.

Tasting notes on Purple Pages of JancisRobinson.com. Stockists from winesearcher.com

——————————————-

Recommended Chinese wines

These were my personal favourites from 53 better-than-average Chinese wines tasted blind in Shanghai. But they will be difficult to find. Many Chinese wines have been made specifically for the (now much restricted) official “gift” market and are never offered to the public.

● Ningxia Kanaan Winery, Cabernet Sauvignon 2011, Ningxia

● QingDao Great River Hill Winery, Château Nine Peaks Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon 2011, Shandong

● Citic Guoan Wine Cabernet Sauvignon 2012, Xinjiang

● Xinya Wine Co Reserve, Cabernet Sauvignon 2008, Xinjiang

● Château Jin Sha Ya Lan Cabernet Sauvignon 2012, Ningxia

● Xinjiang Zhongfei Winery, Château Zhongfei Merlot 2013, Xinjiang

——————————————-

To comment on this article please post below, or email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments