New London theatre about the first world war

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It will be difficult to escape the war of 1914-1918 across all artistic platforms in London in this anniversary year.

While British historians and politicians are quarrelling over its causes as though it only happened last week, a battalion of documentaries, films, plays, exhibitions and books comes marching steadily forth. On stage the big guns include revivals of Sean O’Casey’s rarely seen The Silver Tassie at the National Theatre and Joan Littlewood’s groundbreaking Oh What A Lovely War at the venue of its original creation in 1963, the Theatre Royal Stratford East.

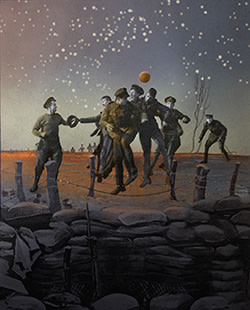

Howard Brenton’s new play Doctor Scroggy’s War opens at the Globe in the summer, and adaptations of bestselling novels Birdsong and Regeneration are due later in the year. The Royal Shakespeare Company is setting two of the Bard’s comedies in a first world war context, and has commissioned a new play by Phil Porter, The Christmas Truce. Much, much more is to come.

Questions about memory and forgetfulness inevitably crop up in the face of all this nostalgia. Original wartime audiences wanted anything but to be reminded of the grim realities of warfare. Kate Dorney, curator of modern and contemporary performance at the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, thinks the theatre of the period warrants further attention. “What’s interesting is that no one ever talks about it. We go from the appearance of the New Woman and Ibsen and Shaw, straight to Noël Coward, and everyone passes over what’s in between.”

She concedes: “A lot of the theatre was very light and fluffy. Revue was the dominant feature during the war. It was all about spectacle.” The runaway success in London’s West End from 1916 onwards, numbering thousands of performances, was the jolly revue Chu Chin Chow. Soldiers especially appreciated the scantily clad dancing girls, until the authorities stepped in to censor their fun.

Even a decade or more after the war the appetite for searing drama about the conflict was muted. The Silver Tassie was turned down in 1928 by WB Yeats, in his capacity as head of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, on the grounds that O’Casey, having not experienced war himself, couldn’t possibly write about it. O’Casey himself called the piece, which attacks the human cost of “imperialist” wars, “A generous handful of stones, aimed indiscriminately, with the aim of breaking a few windows.”

But criticism of war still didn’t go down well when the play was eventually staged in Ireland in 1935: the controversy was so fierce that it closed after five performances.

Tassie’s coup de théâtre is its extraordinary second act, a sort of Expressionist nightmare set in the trenches, complete with a mysterious Death-like figure, the Croucher. The director of the National’s production, Howard Davies, comments: “[O’Casey] sets it up as if it is a Dublin tenement play like Juno and the Paycock. Every character type that you expect is there, then he completely shelves that and goes into another form of writing in order to express his anger and disgust at the first world war, and the pain and horror and the waste of it all.”

Rehearsals begin in three weeks, and Davies is already sounding nervous. “It’s not one of those [plays] that is done on a regular basis, because of the phenomenal difficulty of how to stage and design the transition from a Dublin tenement play into the trenches of the first world war. I think that’s really hard for any director and designer to pull off. I’m scaring myself when I say it!”

Reading Tassie now, I was struck by the almost novelistic attention to detail in the stage directions, which spell out exactly what characters should look like and every element of the set design. How seriously does a modern director take all this?

Davies is firm. “I don’t want this to be a production done in a university drama department way, straight out of a history book. I don’t think that serves theatre as we know it today. It has to be something that is going to speak to today’s audience, rather than an audience in the 1920s or 1930s.”

The Silver Tassie’s presentation of its wounded heroes is likely to shock modern audiences. The maimed men seem almost to be chucked on the scrapheap at the end. Sadly, this is a message Davies sees as equally relevant today. We may have more overt sympathy for maimed veterans, but we prefer them to be relentlessly cheerful and positive.

“Harry [the protagonist] is bitter and sardonic, and feels deeply betrayed, both by the society he fought for and his girlfriend who has moved on. She’s never going to have a child with him; and cruel and selfish though it is, [her behaviour] is understandable in a way.”

Playwright and director Peter Gill is deep in rehearsals for his new play Versailles, starring Francesca Annis as Edith, a grand matriarch pulling her family together after the war.

“For my generation, the Treaty of Versailles [in 1919] was a big thing. We were brought up to believe that the seeds of what was to happen later in the 1930s were sown then.”

In preparation for writing, he read Maynard Keynes’s 1919 The Economic Consequences of the Peace. “He said there would be a war in 20 years’ time and there was! That was in my mind. Somehow I wanted to write a play not about a famous person but a famous historical moment. I wanted to write about a middle-class boy.”

The boy in question is idealistic Leonard, Edith’s clever son who heads off as part of the British delegation to Versailles with very firm ideas. It’s a play of ideas, where fiercely articulate characters debate moral choices. Our modern view of the 1914-1918 war tends to revolve around the figure of the hapless Tommy, the “lion led by donkeys”, the unknown soldier whose suffering stands for the fate of millions. But Gill has chosen a different focus. “I’ve written many plays about working-class people. Without being portentous, I wanted to write about the middle class because at the moment they’re not really stepping up to the mark, are they?”

He smiles over his hastily consumed bowl of pasta, as we meet for a hurried lunch. “They seem to have lost their historic destiny.”

A fascinating trio of plays at Southwark Playhouse highlights another perspective, under the title What the Women Did. While the war liberated women for work, and altered some social conventions for ever, it also, as Kate Dorney stresses, boosted their output in the theatre, with women increasingly writing and directing while the men were at the front. One intriguing contemporary detail is the unseemly interest that some women had in the official government handouts for soldier’s dependants, which also features in Tassie.

“The women at home who are left behind are only too keen to get their hands on the money when the boys are away,” comments Davies. “Teddy’s wife is just desperate for him to get back to the front so she can get her money and live on it in a relatively well-off way.”

In Versailles, Gill looks at the most tangible record of the war for those of us around today – the war memorials which were just beginning to be erected at the time the play is set. “That came out in the writing,” Gill says. “As a young man I was offended by the romanticism of the great Hyde Park war memorials, and now I find them beautiful and moving.”

Like O’Casey, Gill understands the pragmatism of the surviving characters, unattractive though it may be. “We are programmed to forget, otherwise we wouldn’t get on.” However, it’s the responsibility of the artist to keep memory alive. “We have a duty in the intellectual world to remind the politicians in some way,” he says.

Not a nostalgia-fest, then, but a vital recalibration for the modern world.

This article was amended on February 10. It originally stated that the Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1918; it was actually signed in 1919.

Comments