The trouble with legacies

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

History does not really remember people. It constantly redefines them.

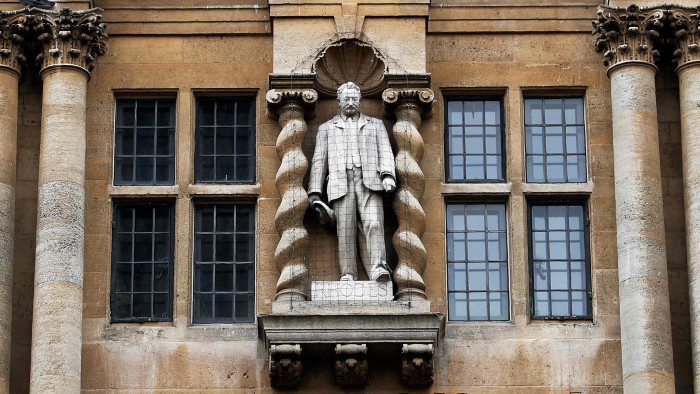

I am not at all surprised that donors to Oriel College, Oxford, reacted angrily when the college said it may take down a statue of one of its most generous benefactors, Cecil Rhodes. The plaques and statuary that accompany the endowment of universities and the naming of buildings are the modern philanthropist’s attempt to thwart that fundamental truth. It is a horror to be reminded of it. By leaving a philanthropic legacy, the wealthy are attempting to pre-define their own history, but no amount of stone can fix what the future will say about you.

Taking their cue from the 2015 RhodesMustFall campaign in South Africa, where the colonialist’s legacy includes the establishment of apartheid and a litany of writings about the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race, Oxford students protested against the statue, which they regarded as a racist affront. Alumni, academics and weighty commentators countered that the protesters were trying to airbrush away the complexities of the past. In the end, a decisive intervention may have been a memo from Oriel’s fundraising director, Sean Power, who summarised the comments of the college’s modern benefactors thus: “Is this how we treat our donors, etc.”

I have no strong view on the controversy at Oriel (though it seems to me the removal of statues can have a powerful political impact in the present and express our hopes for the future), but I do think the episode ought to make philanthropists think about what it means to put their names to an academic institution or scholarship.

Around the world, students are becoming more willing to debate and challenge legacies left by donors and famous alumni. This is particularly the case in the US, where the market economy of philanthropic naming rights is most developed, and could be most disrupted.

The mass shooting at a black church in Charleston last year, which the white suspect is alleged to have hoped would start a race war, prompted another attempt to re-christen Calhoun College at Yale, which is named after the pro-slavery senator John Calhoun. Princeton students have protested against the use of Woodrow Wilson’s name on its School of Public and International Affairs because the early 20th-century US president is said to have opposed the extension of rights to African-Americans.

Even Thomas Jefferson, a founding father no less, has suffered the indignity of being plastered with Post-it notes at the College of William & Mary and the University of Missouri. The notes call him a racist and a rapist, and denounce his ownership of slaves.

Could a similar fate await today’s philanthropists, who direct the lion’s share of their giving to academic institutions? Who will be the subjects of the #MustFall campaigns of the 22nd century? I will not speculate on names, because I do not want anyone to think I see any equivalence between ambitious donors of the present and the Rhodeses and Calhouns of the past.

But, yes, it could happen to today’s mega-donors, even if it takes a leap of John Lennon proportions. Imagine religious donors, redefined as oppressors of gay and lesbian people (it’s easy if you try). Imagine a post-capitalist world, where the possessions of the 1 per cent today are redefined tomorrow as stolen goods (I wonder if you can).

It may not even take 100 years for the current benefactors of academic institutions to become engulfed by controversy. Liberal students in the US are running a campaign to “unKoch your campus”, by highlighting where the conservative Koch brothers have directed funds to encourage the study of entrepreneurship and free market economics. It may not be long until families who became rich on fossil fuels find their monuments under attack.

Universities in the US are becoming more dependent on donations from legacy-minded alumni. Investment returns on their endowments have not met targets, despite the equity bull run. As they step up their efforts to woo the wealthy, they are likely to dangle more naming rights and other ostentations.

But think carefully. To put your name on a building or a fellowship, or to hope for a statue to your generosity, is to make a futile demand of history. It is a request to be remembered, but in fact it is only an invitation to be judged.

Stephen Foley is the FT’s US investment correspondent

Comments