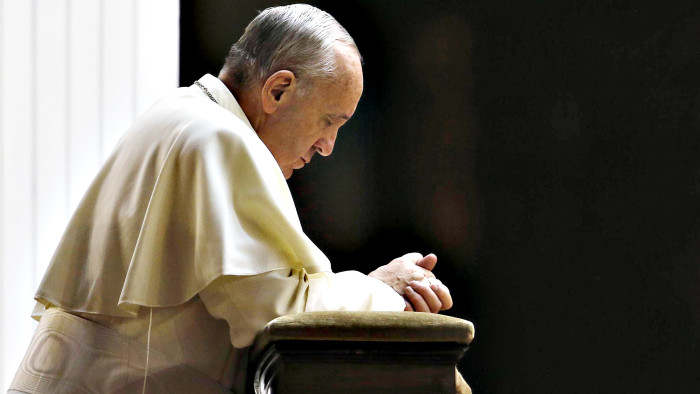

Pope Francis’s papacy one year on

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In March last year an unfamiliar figure stepped on to the balcony above St Peter’s Square in Rome to be greeted as Pope Francis I. Jorge Mario Bergoglio, an Argentine bishop virtually unknown outside Latin America, spoke to the crowds in an affable, unceremonious manner. His style, which seems to embrace and engage people at their own level, has continued to inspire Catholics and non-Catholics alike. Pastors across the world have reported, albeit cautiously, a swelling of their congregations. Pilgrim travel to Rome is breaking all records – and Francis has made the covers of Time magazine (as its 2013 Person of the Year) and, perhaps more remarkably, last month’s Rolling Stone.

As he prepares to celebrate the first anniversary of his election on March 13, Francis’s vision for the Roman Catholic Church is now increasingly clear. He is focusing on the poor of the world, and the “lost sheep”: the untold millions of the world’s 1.2bn faithful who have left the Church in recent years, many because they disagree with official Catholic strictures on sexual morality.

Already 77, and not in the best of health (he has only one lung), Francis is a man in a hurry. Yet his proposals, while widely popular, have also prompted criticism and resistance from influential conservative Roman Catholic groups in the US and elsewhere. Francis, in their view, appears to be promoting anti-capitalist solutions to poverty and liberal attitudes towards sexual sin.

Francis is uniquely qualified, both pastorally and temperamentally, to understand the predicament of marginalised peoples. Some of his more popular predecessors did share something of this quality, including the two who are to be canonised as saints next month: John XXIII (1958-63), who preached lessons of love for all; and John Paul II (1978-2005), who helped bring about the collapse of Soviet communism (“the tree was rotten, I just gave it a shake”).

Francis is, however, the only pope of the modern era who has previously lived and worked among slum dwellers and ministered to a populace that had suffered decades of poverty and violence. As Archbishop of Buenos Aires (1998-2013), he moved out of the episcopal palace to live in a small flat where he cooked for himself, and travelled by bus rather than chauffeur-driven limo.

On Saturday nights in his latter years as Archbishop, he routinely went to the seamiest, most poverty-stricken depths of the city’s red-light district, dressed simply as a priest. Sitting on a street bench he talked with prostitutes, listening to their problems and offering spiritual comfort.

When asked, after his election to the papacy, how he would characterise his personality, Bergoglio said: “I am a sinner. This is the most accurate definition. It is not a figure of speech . . . I am a sinner.” This admission seems key to understanding the reforming approach of his papacy. But what kind of sinner did he have in mind?

In his early career, Bergoglio was the leader of Argentina’s Jesuits, members of the Society of Jesus, an order founded in Spain in 1540 and famous for its militancy and discipline. This period coincided with the “dirty war” of the 1970s between the ruling junta and neo-Marxist groups. Bergoglio had been accused by members of his own religious order of failing to help two arrested worker priests, one of whom was tortured. Whatever happened during that dark time, by the late 1980s he appears to have undergone an extraordinary transformation. He became the “Bishop of the Slums” – and a thorn in the side of Argentina’s political elite.

Francis is unique in other significant ways. He is the first pope to take the name Francis, after the medieval animal-loving saint who was dedicated to preaching and poverty; he is the first pope from the Americas; the first to be a Jesuit. He is also the first pope in 600 years to take office while his predecessor, Benedict XVI, is still alive.

Pope Francis has inherited a Church afflicted by a combination of crises and scandals. The clerical sexual abuse of children, involving thousands of priests and their victims, has undermined the Catholic Church’s claim to moral authority. In the US alone, an estimated $2bn has been paid out by the Church in compensation to victims. At the same time, the Vatican bureaucracy, known as the Curia, has been accused variously of corruption, money laundering, links with the mafia, and gay sexual scandals.

A month into his papacy, Francis created a committee of eight cardinals (known as “the G8”) charged with investigating Vatican bureaucracy. Last month he appointed Cardinal George Pell, an Australian with a reputation for toughness, to become head of the secretariat for the economy, which will oversee financial best practice and transparency. If all goes according to plan, Vatican finances, the subject of an FT investigation last year, are set to become a model of international probity.

Francis has already shown himself to be a stern defender of redistribution of wealth, and job creation; as opposed to the generation of wealth. Last November, Francis published his bookEvangelii Gaudium (Joy of the Gospel) which confirmed his distrust of capitalism and globalisation as offering a serious solution to world poverty. Capitalism, he told Abraham Skorka, a prominent Argentine rabbi, in a 2010 book of their conversations, is the reason that “hedonistic, consumerist and narcissistic cultures have infiltrated Catholicism”. And globalisation, he continued, “is essentially imperialist and instrumentally liberal, but it is not human. In the end it is a way to enslave nations.”

Francis preaches that poverty is a virtue to be cherished and practised for its own sake. His spirituality is Franciscan: “Francis of Assisi”, he says, “contributed an entire concept about poverty to Christianity in the face of the wealth and pride and vanity of the civil and ecclesial powers of the time.”

There is, however, a queasy paradox in his conviction that people should both espouse and value poverty, and at the same time be taken out of it. Prominent American Catholics, such as social scientist Michael Novak, and non-Catholic commentators, such as Rush Limbaugh, have labelled Francis economically naive.

Parallel with his mission to the poor, Francis has announced his determination to bring back into the fold those Catholics who have strayed: the Church’s “sinners”. He has been alarmed by the ever-widening gap between official doctrinal teaching on sin and virtue, as opposed to the actual beliefs and habits of practising Catholics. In Latin America, where 40 per cent of the world’s Roman Catholics now live, Church leaders are conscious that the growth of affluent middle classes is inextricably connected with family planning, and hence the use of contraception.

To the astonishment of many bishops, as well as the lay faithful, Francis has invited Catholics worldwide to send in their opinions on sexual morality. This is a prelude to a major synod (or gathering of bishops) that will meet in Rome this autumn to discuss “the family”. For conservatives this looks like the beginnings of doctrine-by-focus-groups. Irish bishops have followed those of England and Wales in keeping secret the results of their surveys. A recent independent poll among Catholics in Germany revealed that 90 per cent of Catholics refused to believe that contraception was a sin.

Another recent poll by the Spanish-language broadcaster Univision (surveying opinions in 12 countries in Asia and Africa), reveals that plenty of Catholics dispute even the Church’s non-negotiable ban on abortion. Only a third of those surveyed agreed that abortion “should not be allowed at all”, while 57 per cent said it should be legal in some cases.

Successive popes have preached the grave sinfulness of contraception, sex before marriage, divorce and remarriage, the “disorder” of homosexuality. But the faithful for several decades now have shown their rejection of these teachings by lapsing in their millions, or by continuing to practise their faith while repudiating the doctrines.

The most significant evidence of dissent among practising yet sexually “errant” Catholics is their reception of the Eucharist (the consecrated bread and wine) at Mass, without having confessed to a priest and made a “firm purpose of amendment”. The Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), an American Catholic social survey group, estimates that only two per cent of Catholics attend confession in the US. Most other countries have stopped including questions about confession in their surveys since it is obvious that the practice – once so central to the life of the Church – has virtually ceased.

The fate of Catholic confession under Francis’s papacy will be a crucial factor in addressing what the split between teaching and practice will be. Francis, along with many bishops, is striving to tempt the faithful back to the sacrament of confession, now known as “reconciliation”. At a weekly general audience in February, he told pilgrims: “If a lot of time has passed, don’t lose even one more day. Go! The priest will be good. Jesus will be there and he’s even nicer than the priest.”

In this talk he also tackled a crucial argument used by Catholics to avoid confession: that it is God alone who forgives. “You can say God forgives me but our sins are also against our brothers and sisters, against the Church, which is why it is necessary to ask forgiveness in the person of a priest.” In other words a Catholic’s grave sins (and all sexual sins are grave, in the Church’s view) remain unforgiven until confessed to a priest.

The decline of confession is symptomatic of a paradigm shift within Catholicism – from the priest’s power of absolution to the freedom of the individual conscience. For centuries, confession to a priest was the means by which the Roman Catholic Church bestowed spiritual beneficence, while exerting control over the faithful. According to strict Church teaching (originally laid down in 1215 and never abrogated), Catholics are still obliged to confess their sins at least once a year, or suffer self-excommunication.

The sacrament has enjoyed three historic periods of enthusiasm in the past 800 years, each ending with perceived or real abuse of the practice. At the Reformation in the 16th century, confession was widely perceived as an opportunity to abuse women: Martin Luther wrote a major tract against confession. The confessional box, creating a physical division between confessor and penitent, was invented by Catholic counter-reformers to end physical contact during confession (traditionally the penitent had knelt before a seated confessor, often leaning on his lap).

A second collapse occurred during the 19th century, largely a result of husbands’ accusations that their wives’ sexual lives were being controlled by confessors.

In 1910, Pope Pius X attempted to halt what he saw as a tide of secularism and materialism by decreeing that children should make their first confession at seven rather than at 13 or 14, as had been the case for centuries. He further advocated that all the laity should confess once a week rather than once a year.

Many children suffered a sense of oppression in the confessional as a result, as testified by Catholic writers – from James Joyce to Tobias Wolff. A significant minority of children, moreover, were victims of sexually abusing priests in the confessional.

If Francis is to bring back the untold millions of marginalised Catholics, he may need to make a substantial, compassionate gesture. He may need to concede that Church teaching on sexual matters is more of an ideal than an absolute condition of remaining in good standing with the Church. In an interview with a Jesuit magazine last September he declared that there had been too much focus on sexual sins to the detriment of more important social sins.

Francis is unlikely to abandon his call for a return to the ritual of absolution of sin by a priest. But he may take up a cause that many pastors have campaigned for: the return of the rite of general, or public, absolution (as opposed to one-to-one absolution through confession).

General absolution allowed a congregation to examine their consciences in private and receive absolution as a group rather than individually. Brought in by Paul VI in the 1970s, the practice was revoked by John Paul II in 1984.

Any profound change in Catholic teaching, especially within sexual, life and family ethics will have repercussions for the antagonistic divide between liberals and traditionalists, mostly conducted, often virulently, in the Catholic media. And any attempt at radical rewriting of doctrine could lead to a conservative challenge to papal authority, with calls to heed the teaching of Francis’s predecessor, Benedict XVI, who is still present and visible in the Vatican.

Loyalty to the pope remains a crucial factor in prized Catholic unity. The existence of two popes, however, unprecedented for 600 years, has the potential to weaken papal authority.

Francis’s winning, homespun personality appears for now to be inspiring devotion even among those who disagree with him on major issues. But the conclusions of this year’s synod on “the family” are likely, nevertheless, to define his papacy, however long it lasts.

Today many Roman Catholics are looking to Francis for a new era of compassion for human “irregularities”. If their hopes are met, the Catholic Church could even enjoy a renaissance, a mass return of those who have until now let their faith lapse.

The pope’s very popularity and modernity brings with it dangers, however, that any concessions on hallowed, time-honoured doctrines could threaten dissent, even schism. Schisms have happened often enough within the Catholic Church – and they could happen again.

John Cornwell’s ‘The Dark Box: A Secret History of Confession’ is published by Profile Books in the UK, and by Basic Books in the US

Comments