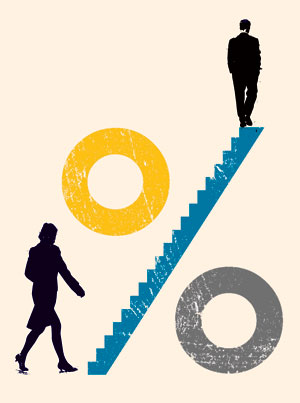

Central banking: still a man’s world

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A few years ago I participated in a central banking conference in New York. As I looked around the airless room, I noticed something striking: the seats were almost exclusively filled with dark male suits and sober white shirts, with barely a woman in sight.

This is not the first time I have felt in the minority. Early in my life I worked in Islamic regions of the world, where there were few women in public life. Later I was the FT bureau chief in Japan, where it was so novel to see a young woman in a position of authority that a kindly Japanese diplomat told me to put “Dr Tett” on my name cards, to avoid having to remind anyone that I was a “Miss”. It was great advice.

But what made this banking seminar so notable – and memorable – was that it occurred in New York, not Iran. And while the gender imbalance that day was extreme, it was not that unusual: in two decades of reporting on central bank activity I have met very few senior women.

Does this matter? The issue is now provoking lively debate in America as Barack Obama prepares to select the next chairman of the Federal Reserve. On paper, Janet Yellen, 66, the current vice-chair, seems an obvious contender: she is an accomplished economist with extensive government experience and – unlike many of her colleagues – not associated with bubble-era regulatory mistakes. But Larry Summers, 58, former Treasury secretary (and FT columnist) is also gathering support from the White House. This enrages some Democrats, who criticise Summers for previous regulatory mistakes and an abrasive style. There is another factor too: many female politicians want a female chairman, given that this has never happened in the Fed’s 100-year history. Conversely, Summers’ fans insist he has better intellectual credentials – and that gender should be taken out of the debate.

What should we make of this? When the fight first erupted, I must confess that I squirmed. I daresay many FT readers did too. Women have sweated blood to be judged on their own merits in past years. The idea of appointing Yellen to make a gender point sounds patronising and regressive. After all, she would have enough credentials even if she was a blue-spotted Martian. The main distinction between her and Summers is not policy but their style; both seem reasonable candidates.

But while I dislike the fact that gender has reared its ugly head, it does have one benefit. Since the 2008 financial crisis erupted, private sector banks have been roundly – and rightly – criticised for the lack of senior women; if Lehman Brothers had been “Lehman Sisters”, the quip goes, there would have been less testosterone-fuelled risk-taking. But what has gone largely unnoticed – until now – is that this gender imbalance is mirrored in the public sector too. To be fair, the pattern is not at bad as it used to be. Federal Reserve data, for example, suggest that women make up 45 per cent of its staff. The 2013 Central Bank Directory reports a similar ratio for the central banking community as a whole. But though this sounds impressive on paper, women are notably under-represented in the most influential economic roles. Just a quarter of participants, for example, on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee are women. In Europe, the ratio of senior women is far lower. And globally, just 17 of the world’s 177 central bank governors are women – and almost all of these are in emerging market countries (think of Russia, Lesotho or the Seychelles).

It is not difficult to spot the reasons for this. Rising through the ranks of a central bank requires extremely long hours over many years. That is tough to combine with family life, particularly in Europe where bureaucrats do not hop in and out of public service. Having a PhD in economics also tends to be de rigueur these days. However, as a 2011 study for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco notes, there has been a “persistent underrepresentation of women in economics” in recent years at universities.

To their credit, the central banks – as Yellen herself likes to stress – are trying to rectify this. I recently met with the 2012 new recruits at the Bank of England, for example, and noticed that almost half the people in the room were women and many were also non-white. Strikingly, there was also a large number of people who had not studied economics.

But it is one thing to get a more diverse selection of recruits; it is quite another to ensure that these rise up through the ranks. This matters. Not – let me stress – because women have any magical powers or superior skills but because getting a diversity of views, experiences, gender, age and communication styles helps to prevent tunnel vision. Or to put it another way, the key issue that hangs over regulators and bankers alike is how to break down the clubby patterns of thinking and groupthink. And that problem will not be fixed simply by having a female Fed chair – even if that person turns out to be the (now controversial) Yellen.

——————————————-

Letters in response to this column:

Among the finest / From Mr Rudolf Gouws

All I can picture is Larry snoozing / From Ms Alice Bray

Comments