Sterling and Brexit: the lessons from past crashes

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

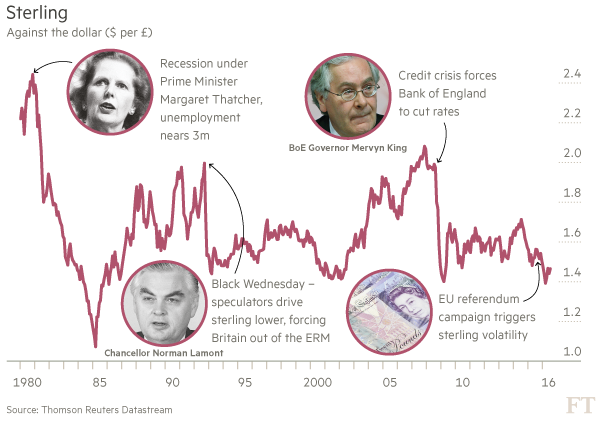

Sterling’s pendulum mechanism is in full working order, veering sharply back and forth to the rhythm of EU referendum opinion poll findings and expected to oscillate further as the market digests the outcome of Thursday’s knife-edge vote.

If the final days of the campaign are any guide, the pendulum may soon be swinging out of control. Monday’s 2.4 per cent rise, sterling’s third-biggest one-day rise in 10 years, follows the pound’s dive last Thursday to $1.40, a level it has rarely breached.

Such is the unknown dimension of the referendum and the consequences of a vote to leave, analysts are struggling to plot a path for the pound beyond the short term.

Broadly, they assume sterling quite quickly bounces to $1.50 and more on a Remain outcome, and drops equally rapidly — by anything from 10 to 20 per cent — if the UK votes to leave.

And after that? “It is a difficult period to predict, given the potential structural changes to the UK economy and the uncertain environment,” says Roger Hallam, chief investment officer in currencies at JPMorgan Asset Management.

George Soros, the currency speculator who helped bring about Black Wednesday in 1992, when sterling lost 15 per cent and forced Britain out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, has no qualms predicting the future. He says Brexit will signal a more tempestuous period for the pound than the one it endured 24 years ago.

“I would expect this devaluation to be bigger and more disruptive,” he wrote in the Guardian newspaper this week.

Currency devaluations are not always problematic. Sterling has had more than its fair share of them.

According to Simon Derrick, chief market strategist at BNY Mellon, the 1981 recession, Black Wednesday and the 2008 crash resulted in the pound falling by at least a quarter over six-month periods. Since 1975, sterling has dropped 15 per cent over six months on six other occasions.

After the initial shock of the 15 per cent devaluation in 1992, the UK economy enjoyed the freedom of no longer having to sustain an artificially high currency and had the flexibility to cut interest rates.

Black Wednesday became, to some economists, White Wednesday. As FX G10 strategist Steven Barrow at Standard Bank says, “People realised that escaping the straitjacket of the ERM was a good thing for the UK’s recessionary economy at the time. Hence a sterling bounceback here was to be expected.”

Much the same was evident after the 2008 crash — sterling again dropped steeply, by 15 per cent on a trade-weighted basis, and the Bank of England again cut rates.

“One of the reasons currencies adjust is to cushion economic slowdowns,” says John Wraith, head of UK rates strategy at UBS. The UK was exposed to the financial crisis, so sterling needed to fall.

“Having hit the bottom it triggered the recovery that the UK has actually been enjoying ever since, going on almost 7 years, and in the meantime sterling has regained a bit of altitude.”

As currency traders prepare for an all-night vigil at their desks on Thursday, they will be buying and selling sterling at already elevated levels, according to BNP Paribas’s valuation model.

The pound has been here before. “The losses seen for sterling in 1981, 1992 and 2008 came when the currency had been trading at elevated levels against the dollar,” says Mr Derrick.

But comparisons with 2008 are not helpful, according to Mr Barrow. No one had any idea what the economic cost of the credit crisis would be, whereas the market can see the vote coming and estimate the consequences.

“So although the pound will still collapse on a Brexit vote there might be less ‘groping for the downside’,” he says — the kind that in 2008 saw sterling overshoot from $2 to $1.35, before steadying to $1.50.

A vote to leave would see sterling fall sharply in the first instance — “a short sharp shock seems reasonable”, according to Mr Hallam.

From then, says Mr Wraith, its path depends on how the UK economy rebalances, on trade negotiations, and how the process for leaving the EU unfolds.

“It may well be the case that in a year or two from now sterling has hit the bottom and started climbing again — as long as the recovery does likewise,” he adds.

It is possible to see sterling overshoot to $1.20 followed by stability at $1.40, says Mr Barrow. There is also the other side of the sterling-dollar trade to consider, he notes — how, as a pointer towards prevailing trends in the west, Brexit could weaken Europe, the political elite and faith in experts, and strengthen Trumpism, insularity and anti-immigration, all of which could drive the dollar lower.

The pendulum will swing back and forth, but eventually the pound may end up where it began the year. But investors may need a lot of patience and an awful lot of luck to come through that experience in one piece.

Comments