Trade propels renminbi on route to global reserve currency

Simply sign up to the Currencies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When discussing the internationalisation of China’s renminbi, Denis Shulakov, first vice-president of Gazprombank in Moscow, is fond of quoting Wayne Gretzky, the former Canadian ice hockey player and coach.

“You don’t need to be where the puck is, you need to be where the puck is going to be,” he says.

Gazprombank, like many Russian banks, is furiously working to set up operations in both Hong Kong and on the Chinese mainland in preparation for conducting more trade and finance in China’s renminbi: “All the Russian corporates who are key clients of the bank are moving in this direction,” explains Mr Shulakov, who says his organisation expects to be the first Russian bank to obtain a broker dealer licence in Hong Kong.

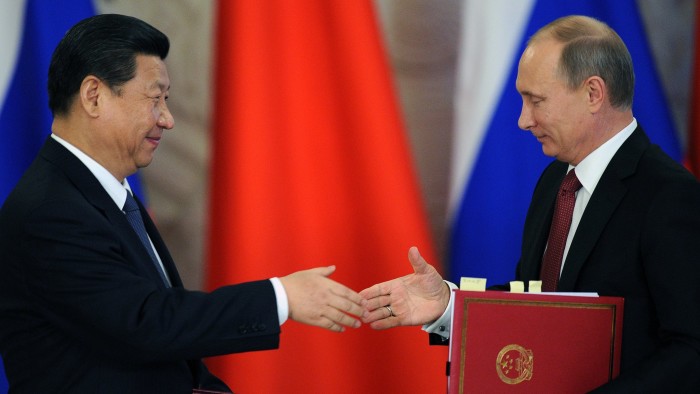

There is a good reason why Russian companies would be showing a keen interest in China’s currency for both trade settlement and finance: sanctions against Russia have frozen access to funds in the west. But for other banks and companies around the world, the reasons are just as compelling.

The past five years have seen a surge into the renminbi as a way to settle trade with the world’s largest exporter, a trend enthusiastically supported by Beijing as a means to push its long-declared goal of having a global reserve currency, commensurate with the dollar, the yen and the euro.

Already 22 per cent of China’s trade is being settled in renminbi, up from 8 per cent in 2012 and zero five years ago, according to estimates by Citi.

Bruce Alter, head of trade and receivables finance for HSBC in China, reels off a list of companies that he has worked with to do deals in renminbi: an Australian seafood exporter, a Malaysian palm oil producer, a Chinese bus manufacturer selling to Brazil and a Canadian furniture retailer.

“If you look at Rmb trade flows 2-3 years ago, it was really dominated by Hong Kong China trade, but you see today, although there is still a lot of Hong Kong in the mix, there are more companies from more markets getting into the Rmb game,” he says.

He says the main benefit of using the renminbi is that for large importers (often retailers) it is cheaper – it removes the foreign exchange margin from the contract and often Chinese companies will offer a discount of 1-2 per cent if buyers pay in renminbi.

As for overseas sellers, agreeing to trade in renminbi gives them a better chance of penetrating the Chinese market. One additional motivation is that if overseas sellers already have operations in China, they can use the renminbi export proceeds to cover their Chinese operational costs.

In addition to hubs such as Hong Kong, Singapore and London, many more countries are now also involved in offshore renminbi, with China actively promoting greater adoption of its currency in trade and finance. Central banks in countries as far apart as Malaysia, Nigeria and Chile hold part of their foreign exchange reserves in renminbi. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has set up dozens of arrangements with its counterparts around the world, allowing it to swap renminbi for those parties’ currencies.

“On the trade and commerce aspect, the currency is fully liberal,” says Sandip Patil, Citi’s Asia managing director for global liquidity and investments. “Any company can use Rmb whichever way they like to conduct international trade and associated working capital financing.”

He adds: “Many times you are able to negotiate larger discounts with your suppliers if you are paying in Rmb” because paying in foreign currency creates procedural bottlenecks and delays.

But compared with its surging use in trade, the renminbi still has little take-up in capital markets, despite concerted efforts by the Chinese government. This is mainly because of continuing restrictions on the ability to convert and transfer the currency.

Podcast

The growing influence of China’s renminbi

Ten years ago the Chinese government ended the renminbi’s strict peg against the US dollar. Since then the currency has gained in stature in world trade, investment and as a reserve currency, reflecting China’s growing international influence. James Kynge asks David Pavitt of HSBC and Jinny Yan of Standard Chartered what further changes are in store.

Read more at ft.com/renminbi.

Once it obtains a broker licence in Hong Kong, Gazprombank is keen to access what it estimates to be a $6tn pool of finance in the onshore China market through “panda bonds”, Chinese renminbi-denominated bonds issued in China by a non-Chinese issuer. “The only problem with the yuan is conversion and transfer,” says Mr Shulakov. “If you have onshore yuan you cannot freely convert it and transfer it.”

Zhou Xiaochuan, China’s central bank governor, has said it is committed to liberalising China’s capital account, but stops short of wanting the renminbi to be fully and freely convertible in capital markets transactions. In a speech in April, Mr Zhou used the term “managed convertibility”.

Meanwhile, discussion with the International Monetary Fund over including the renminbi in the basket of currencies used to denominate the IMF’s special drawing rights (SDR) would open the way for reserve currency status, if the Fund gave a green light during its five year review in November. But many are sceptical that this will happen.

Dennis Tan, foreign exchange strategist for Barclays, said China has met only a few of the prerequisites for being an SDR currency and that the low usage of Rmb in international financial transactions is a potential hindrance. “In volume of trade flows and exports, obviously China has made it into the club,” he says, But in other measures, such as currency denomination of international banking liabilities and or global reserves, the Rmb still falls short, he says.

Mr Shulakov, though, is optimistic. “We are yet to experience the opening up of the Chinese local market,” he says, “but it is going to happen, inevitably. So we are in discussions and we are preparing ourselves for this, just as the Morgan Stanleys and Goldman Sachs of this world are doing.”

Comments