Lunch with the FT: Jeremy Deller

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Oliva Nera, the restaurant chosen by Jeremy Deller for our lunch, is a small osteria in a quiet corner of the Castello district of Venice, with a glass front and outdoor tables and chairs that are, today, surprisingly unoccupied. Inside, I find the restaurant empty except for a bespectacled woman who, on seeing me, leaps up from her seat to deliver the news: they are closed for lunch. She had tried to warn the person who made the booking, she says in accented English, but didn’t have the number. As one might expect of an English and an Italian woman in a socially awkward situation, we apologise to each other for some time, and then warmly embrace.

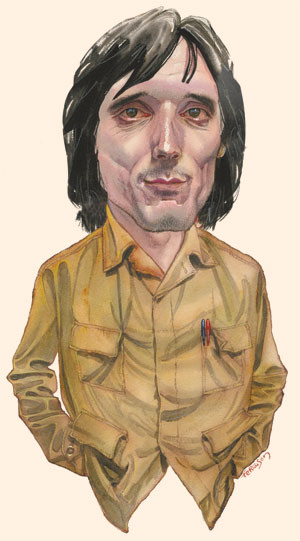

I am pacing outside the restaurant when Deller rounds the corner. A compact figure with straight shoulder-length hair, he is known as a natty dresser; today he is wearing a safari suit, Birkenstock sandals and pink socks, with a neon-pink sweater tied around his waist, and a large straw hat on his head. On hearing the bad news, he looks very grave.

“Shall I talk to her?” he asks. Since Deller once persuaded more than 800 people including 200 former miners to recreate the Battle of Orgreave, a particularly bloody confrontation in the miners’ strike of 1984, for a piece of participatory art, I suspect he might well be able to persuade the restaurant manager to rustle something up. But he peers through the restaurant window and frowns. “Oh, it’s really closed,” he says, which seems to settle it.

Fortunately, Deller knows a place nearby. “You’re lucky I’m not some hotshot like Mark Zuckerberg,” he says as we walk across a bridge. “He would have had a fit.”

In fact, Jeremy Deller, who won the Turner Prize in 2004, is a hotshot – frequently described as one of the most important artists of his generation – and his work, which he calls “social surrealism”, is thought to have broadened the definition of contemporary art. Last year Joy in People, his much-lauded retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, included a documentary about fans of Depeche Mode; the remnants of a car bombed in a Baghdad marketplace, which Deller towed across America as a conversation piece; and a recreation of Valerie’s Snack Bar, a tea room in Manchester popular with pensioners, which was originally a float in a public procession organised by Deller to celebrate the city’s subcultures including goths, smokers and Big Issue sellers. As one admirer put it recently, Deller’s work is “public art that has a genuine respect for the public”.

At 46, he is now representing Britain at the 55th Venice Biennale – one of the greatest accolades, and challenges, for any artist. Two days before the opening, he is feeling confident about the show, he says, although he is distracted with plans for the opening party, which will take place on the Isola della Vignole and which will feature the Melodians Steel Band from Balham, south London, playing cover tracks of 1980s pop. Right now, he says in his low-key way, he’s mostly worried it’s going to rain.

We reach a small iron gate and he leads me into the Trattoria Corte Sconta, which, thankfully, is open, and has a table for us on a pretty and comfortingly busy patio filled with customers in summer dresses and linen blazers, speaking English.

“Oh, hello,” says Deller, noticing that the table of people next to us are beaming at him. One of the diners is Adrian Searle, an art critic for the Guardian, who, Deller tells me, is going to be the first member of the press to see his exhibition, right after lunch. Another is Charlotte Higgins, also a Guardian arts journalist, who says she’s just seen Natasha, Deller’s partner, sitting across the patio at another table with Mark Leckey, an artist who won the Turner Prize in 2008, and Gavin Brown, Deller’s New York gallerist, with his wife.

The garden suddenly feels a little crowded; Deller smiles tensely. Wine at lunch, he says, makes him feel “tired and sort of depressed”, so we order some sparkling water. Studying the menu, we realise neither of us can read Italian, although, says Deller, he studied Latin at Dulwich College, a private school in south London, where his parents – whom he describes as “public-sector middle class” (his mother worked for the NHS; his father for the Tower Hamlets council) – sent him at some sacrifice. “I had what Michael Gove would call the traditional education,” he says, referring to the UK minister of education, “where you just learn by rote – facts, figures, declensions. It killed a lot of subjects for me.”

Deemed untalented at art at school, Deller focused on art history, before attending the Courtauld Institute as an undergraduate. While there he went to an opening of a show at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery, where he met Andy Warhol, and was invited to spend two weeks at the pop artist’s Factory in New York. It was during that stay that he realised he wanted to be an artist himself and that, as he puts it, “You could make art out of whatever you were interested in – you could run a magazine, make film, TV, prints, paintings, music production …”

But becoming an artist took some time. “I had no idea what I was doing basically,” he says about his twenties, when he took an MA in art history at Sussex University, lived with his parents and worked at jobs including postman, driver and shop assistant at Sign of the Times, a Covent Garden clothing shop for which he designed T-shirts featuring lyrics by Philip Larkin.

For the Venice Biennale show Deller has had tote bags and invitations made which, printed in black letters on a bright pink background, read more like a warning than an advertisement: “Please note that this invitation does not grant entry to the Giardini or guarantee entry to the British pavilion.” Deller explains it’s a joke about the exclusive, moneyed atmosphere at Venice, where it’s easy to feel like you’re on the wrong guest list or in the wrong restaurant. “You’ve got to have a bit of fun or it overwhelms you,” he says. “You’ll feel the weight of the country on top of you. People’s expectations of this show are huge.”

A waiter arrives to take our order, and Deller orders sardines in saor (onion and vinegar marinade), followed by gnocchi with aubergine and fish. (Deller has, he says, been a vegetarian since reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals but eats fish “when he has to”.) I order spaghetti with mussels and clams, and ask the waitress if she can recommend a starter, because I haven’t yet located the English section of the menu. She smiles, and says she’ll make me a selection of different kinds of smoked fish.

Deller’s exhibition is in the British pavilion, one of 30 permanent pavilions situated in the old Venetian park known as the Giardini. It’s a very traditional building which Deller says made him think of the museums he visited as a child, and so he decided to play the curator, borrowing objects from other collections – including a Neolithic axe from the British Museum and the mould of a William Morris print from the William Morris Gallery – as well as making and commissioning original work such as videos and murals. The entire show, he explains, is like a miniature museum about England – Ireland, Scotland and Wales have their own separate pavilions – complete with a guidebook and a tea room. Just yesterday, he says, he added a sign that spells out “TEA” in Neolithic arrowheads.

As we wait for our food, I ask whether Deller set out to “represent” Britain, like an athlete at the Olympics. He shakes his head, before admitting that he was probably responding to the British Council’s patriotic agenda by focusing on national aspects that were “debatable or ambiguous” – the war in Iraq, civil riots in Londonderry, tax havens in Jersey – as well as things about England he loves most: wildlife, David Bowie, steel bands.

Our starters arrive – Deller’s sardines chopped into a delicate salad, my different kinds of fish artfully curated on a rustic slab of wood.

While we eat, Deller discreetly fetches from his bag a neon-pink book with the words “English Magic” on the front, taking care not to let the neighbouring table see the exhibition catalogue. With one hand, he opens it at the image of a mural depicting William Morris as a giant, standing in the Venetian lagoon, sinking a ship belonging to Roman Abramovich. During the last biennale, Deller explains, Abramovich’s boat was moored outside the Giardini, blocking the view, and his guards took up half the pavement. Morris – textile designer, libertarian socialist and one of Deller’s heroes – is here a metaphorical colossus, explains Deller, representing the “power of culture over money and business”. He takes a bite of sardine.

The next painting he shows me is of a giant hen harrier, a rare bird of prey; in 2007, says Deller, two of these birds were alleged to have been shot as they flew over Sandringham estate, where Prince Harry and his friend William van Cutsem were reported to have been shooting that day. Deller, insisting he is not a political artist, is interested, he says, in what the royal family represents to British people, and calls the Queen “one of the great performance artists of our time – just a totally blank canvas”.

Deller says that he finds the biennale, with all its socialising, glamour and displays of wealth, in some ways “a bit of a nightmare” – but he loves the way Venetian churches are full of artefacts and artworks from different eras, from the Byzantines to the present day, the effect of which is to create a feeling of time travel, which acts “almost like a narcotic”.

Our main courses arrive, mine a plate of inky black spaghetti and tendrils, with squashed tomatoes, and Deller’s a pool of creamy gnocchi. His own show, he says, is a portrait of England through the ages. He has been reading Supernatural Strategies for Making a Rock’n’Roll Group, a spoof how-to guide by Ian F Svenonius (of the punk group Nation of Ulysses) that treats rock as a kind of mythological phenomenon, and says he is interested in the artist as a kind of mystic – from ancient shamans to pop musicians such as David Bowie. I ask whether Warhol was another such mystical figure, and he nods enthusiastically. “Yes, even in the way he used to speak, in riddles almost – and he looked like a crazy wizard, didn’t he?” He likes the idea of seeing Warhol as more than “just a money-counting person, which he was as well”.

Unlike his contemporaries the Young British Artists, or YBAs, Deller prefers not to make objects to sell, and is also wary of making work that is autobiographical, preferring to portray himself instead as the consummate fan. (Much of his work – such as his exhibition of the letters and drawings of fans of the Manic Street Preachers – has documented fan culture too; as Hayward director Ralph Rugoff has said, Deller is “much more interested in doing things that shine a light on other people’s creativity than in claiming that light for himself”.) In public, he can seem to behave more like a teacher than a contemporary artist; in a recent TV arts show he was shown explaining his work to a classroom of children (dressed, however, as bats – Deller’s favourite mammal). “You mustn’t try to be clever or obfuscate,” says Deller, carefully enunciating each syllable of the final word. “Artists are quite normal people really,” he says. “They’re not all nutters like Tracey Emin.”

I put down my fork for a second to say that I love Tracey Emin, and Deller replies, “I’ll say one thing: she is the Sarah Palin of the art world.” There is a long pause while we both eat and I wonder whether to defend Emin, and then Deller makes a gesture with his fork to the space over my shoulder, and Mark Leckey wanders over carrying his baby daughter, who gazes at Deller, transfixed. Deller asks if Leckey is going to the Arsenale, and Leckey says, yes, he’s going “up the Arse.

“How’s your show?” he continues in his northern accent. “I’ve heard it’s about cheese.” Deller, holding a fork of gnocchi, looks confused before realising that Leckey is teasing him; no one knows what’s in the show, which was kept top secret for months. The pink book is hidden under a napkin. A moment later Searle gets up from the table next to us, telling Deller that he’ll meet him at the Giardini.

Flustered by all the comings and goings, I find myself asking Deller whether he is interested in “relational aesthetics”, a term coined by French art critic Nicolas Bourriaud to describe the kind of artwork that, like Deller’s, might be said to create a kind of community. Deller, who started to shake his head at “relational”, says that reading art theory makes him anxious but admits he thinks good art shouldn’t try to do anything useful, and doesn’t like the way art gets co-opted by politicians to solve social problems. Thinking of “Sacrilege,” Deller’s giant replica of Stonehenge made of bouncy-castle material, which toured Britain last year during the Olympics and was praised by many including London mayor Boris Johnson, I put it to him that the experience of seeing thousands of people respond to his artwork must be euphoric. He shakes his head. “I just retreated into myself,” he says of watching everyone bouncing around on the artwork. “I didn’t want to talk – it was too much, too overwhelming that I’d created this scene of mass happiness.” He shrugs and sits back, apparently finished with his gnocchi.

Our plates cleared, we order two espressos which we sip while chatting about David Cameron, Margaret Thatcher, the 2011 riots, Holloway in north London (where Deller lives), and the Olympics opening ceremony, which Deller liked because it was deafening, like a rock concert. Something makes me ask whether he’s patriotic or not, and he looks thoughtful for a moment. He’s not a “joiner-inner”, he says but, then again, there’s an awful lot about England to love.

He gets up to go to meet Searle at the pavilion, so I say goodbye. But later, having wandered along the lagoon past the Arsenale where the huge cruise ships are moored, towards the Giardini, I spot Deller standing at the top of the pavilion’s steps, in front of the large hen harrier mural, demonstrating to a visiting group of critics and curators how to use a rubber stamp to make a miniature version of the bird image on an A4 sheet. “It isn’t difficult,” he says to one of them, and she presses down on the paper and lifts it up – her own Deller print – for all to see, before slipping it into her tote.

‘English Magic’ is at the British Pavilion, Venice, to November 24.

‘It’s a Kind of English Magic: Notes from the Venice Biennale’ is at the British Council, London, to September 21; visualarts.britishcouncil.org

——————————————-

Trattoria Corte Sconta

Castello, 3886

Calle del Pestrin (Arsenale)

30122 Venezia

Acqua €4

Antipasti €35

Primo piatti €36

Caffe €4

Coperto (cover charge) €6

Total €85

Comments