Airport architecture: flights of fancy

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

At a press conference earlier this year, listening to architect Luis Vidal talk about his design for Heathrow’s new £2.5bn Terminal 2, I heard the word “destination” and my nerves began to jangle. Vidal suggested that this was a new generation of airport, that this was a “gathering place”, a “piazza”, a place people would want to come to whether they were flying or not. He compared the amount of retail space with Covent Garden. By now my teeth were grinding and I wanted to scream: who the hell wants to spend any more time in an airport than they have to?

By the following day I’d calmed down. After all, I thought, airport architects face an invidious conundrum. They are designing a building type that, like a prison, no matter how luxuriously appointed, everyone wants to escape as soon as possible.

As long ago as the 1960s, the French cultural theorist Paul Virilio suggested that the airport concourse would replace the city square as the fundamental site of urban and international interchange. It hasn’t. Few meetings take place in airports. Instead people flying in for even a few hours make great efforts to get away from them – even if it entails hours in traffic or an anonymous airport hotel. People dislike being in airports. And the more they travel, the more they dislike them.

Which gives everyone designing one a problem. All the carefully wrought metaphors of wings and flight, the great curving roofs mirroring the landscape, the views of planes and sky and the intuitive way-finding don’t really matter because, ultimately, they all end up feeling pretty much the same anyway.

Partly this disillusion with the airport as a building type is due to the rapid transformation of flight over the past half-century from exotic treat to everyday annoyance – airports are victims of their own success. A big chunk of the problem is the process of being processed, the small humiliations of exposing your toiletries, of standing beltless in your socks being patted down, the queues, the nagging fear of missing your flight, the overpriced, overfamiliar products in shops which can only survive because they have a captive market comforted by the soothingly familiar act of consumption.

Partly, though, it is also due to the increasingly ubiquitous architectural language which effectively disorients us, desensitising us to where we are. And that is something that architects could control. There is an assumption that glass walls, soaring roofs, stainless steel details and terrazzo floors are the de facto finish for the modern airport. But are they? Why? Why do airports need to look like malls?

The question, then, is what should architects do? Should they just design the most functional, well-engineered spaces possible? Should they attempt to design impressive gateways embodying national pride? Or should they be doing something else entirely?

A slew of airport openings and newly commissioned designs should allow us to take the temperature of the genre, to detect emerging trends.

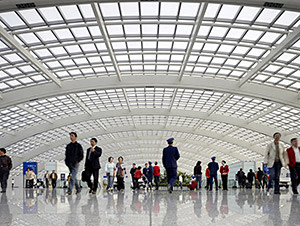

One rather elegant type is what we might call “airport orientalism”. Just as it was in art, orientalism is chiefly an invention of the Occident (pace Edward Said) and mostly then the British, who have managed an incredible dominance of international airport design. Leading that charge is London-based architectural practice Foster & Partners, which started with Stansted, in Essex, and ended with world domination – almost. Its Beijing international airport in particular is an extraordinary structure. When it was completed in 2008, it was the world’s biggest building under one roof.

Last year the firm completed Jordan’s lovely Queen Alia airport, a cool space beneath a roofscape of domed parasols, a space somehow simultaneously shaded and perfectly naturally lit. The same architects’ designs for Kuwait international airport feature elegant concrete vaults, a blend of Grand Central Station’s Roman arches, a Middle Eastern bazaar and Eero Saarinen’s expressionist concrete at JFK’s 1960s TWA terminal.

Another British architect, Sir Nicholas Grimshaw, recently released designs for Istanbul’s new six-runway airport (due to open in 2018 and destined to be the world’s largest terminal under one roof). Here, slender concrete columns support a series of filigree vaults, vaguely Islamic and very elegant.

Grimshaw has also designed the delicate golden origami roofs of St Petersburg’s Pulkovo airport which opened earlier this year; glittering oligarch bling toned down – just enough.

Alongside airport orientalism is the space age, another emerging oeuvre (taking its cue from a 1960s techno-futurism). On top of the heap is Italian architect Massimiliano Fuksas’s astonishing Shenzhen Bao’an airport. A set of perforated tubes, the structure creates a mind-bending landscape, something strikingly unfamiliar. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s new sci-fi Terminal 2 at Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji international airport, with its Mughal mushroom columns and waffle roof, does something similar, if a little more conventionally.

Possibly most impressive of all, however, is the weird and wonderful world of Georgia’s aesthetically integrated transport infrastructure. Here almost the whole caboodle has been entrusted to German architect J Mayer H. Everything from border crossings to motorway service stations have been turned into opportunities for audacious national branding. Mestia’s Queen Tamar airport might be a tiddler, with its terminal building bent upwards like a paper clip to create a viewing tower, but it is also a symbol of a country that is using airports – and everything else it builds – to signal an identity.

Dutch architect UNStudio was also brought in and its design for the red-and-white Kutaisi international airport, with its folded planes and bulging fractal ceiling, is anything but conventional.

Perhaps the most intriguing recent airport story has been about Berlin’s disused Tempelhof, which had become so beloved in its overgrown state that plans to redevelop it were thrown out and its runways will now be turned into a public park.

First built in 1923 and rebuilt in its present form by the Nazis in 1934, it is a rare survivor of the era. Designed in the shape of an eagle (already a heavy piece of symbolism), Tempelhof has a fiercely charged history, as the site of the 1948 Berlin airlift. Its form is that cold yet also rather elegant blend of art deco, modernism and classicism that characterised the Nazi era, a cocktail of limestone, marble and brass. A huge curving canopy sweeps passengers in (this is Foster’s favourite airport and he copied this gesture in Beijing). It had the mass, articulation and permanence of a city station, a place always alive and as solid as the city itself, of which it was determinedly a part.

This old-fashioned airport was, despite its history, hugely popular. Why? In part because it was merely a few minutes from the city centre, so the building felt part of the urban fabric. But it was also that its architecture gave it a scale related to the city, and its materials reassured with their familiarity and a sense of calm (if rather formal) permanence. It was the architecture of the museum and not the mall, a place that reassured and inculcated a sense of place, which allowed travellers to locate themselves somewhere specific (albeit many travellers might not want to locate themselves in Nazi Germany). Only a handful of other airports have done something similar as successfully, such as Budapest’s now-defunct Ferihegy 1 and Copenhagen’s beautiful timber-encased airport.

In the 1930s there were all kinds of proposals for city-centre airports. One was proposed over London’s King’s Cross station and it was envisaged that airships would dock on the crowns of New York skyscrapers. Now it seems that airports will never return to the city centre (though cities are growing outwards to meet them).

Perhaps, however, architects, engineers and airport authorities need to stop thinking in the language of the generic and instead build airports as if they were embedded elements of the metropolis, as grand and solid as the stations once were, buildings scaled to city streets and civic architecture rather than to the blank expanse of runways or to the mega-malls they increasingly resemble.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture critic

——————————————-

Where waiting for a flight is fun

Sauna From August, passengers at Helsinki airport will be able to enjoy a classically Finnish treat while waiting to leave the country, writes Kasia Delgado. Finnair is due to open a unisex sauna in its new business class lounge, as well as private showers. Although Finns traditionally go nude, towels are provided, along with Finnish forest berry-based shampoos and lotions. Other airlines’ passengers can pay €48 to use the sauna.

Golf Seoul’s Incheon airport has an 18-hole golf course five minutes away – a free shuttle bus connects it to the terminal. But for those in a hurry, there’s also a “golf town” within the airport boundaries, offering a 330-yard driving range and 18-hole putting course. Hong Kong International also has a nine-hole course between Terminal 2 and the Marriott airport hotel. Hole seven of the Nine Eagles course even features a green on an island in a man-made lake.

Swimming Numerous airport-perimeter hotels offer pools, and there’s one inside the airside G-Force health club at Dubai International, but Singapore’s Changi airport is in a different league. It boasts a Balinese-themed pool on the roof of Terminal 1, with a whirlpool, cabana beds, a poolside bar and views over the apron. Entry costs S$13.91 (£6.50).

Art Airports often feature work by local artists, but Amsterdam’s Schiphol offers a rather more highbrow take, with an airside offshoot of the city’s celebrated Rijksmuseum. It is currently closed as the airport is refurbished but an improved version is due to reopen next year. Meanwhile Terminal 2E at Paris’s Charles de Gaulle airport has an Espace Musées which displays a revolving collection from some of the city’s best galleries and museums. It is currently showing 17th-century tapestries and furniture. Both are free.

Ice skating For those who still have energy left after their round of golf, Seoul’s Incheon airport also offers the Ice Forest skating rink. Skate hire costs Won4,000 (£2.30).

Photographs: Corbis; LHR Airports Limited; Getty; Nigel Young; Nakanimamasakhlisi; AFP; Reuters; Robert Polidori; Nakanimamasakhlisi; Nigel Young; Marcus Buck; AFP; Yuri Molodkovets; LHR Airports Ltd

Comments