‘El Greco and Modern Painting’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

One Sunday in May this year, 52 residents voted to change the name of their village near Burgos, in northern Spain. It had been known since 1623 as Castrillo Matajudíos (the second word means “kill Jews”) but a majority voted to restore the original name of Mota de Judíos, “Hill of the Jews”. Google Maps has already honoured the decision.

The toponymic activism of this tiny settlement mirrors wider changes in how Spain is re-evaluating its rich, troubled, Jewish past. Barely two weeks later, Spain’s government approved a new law enabling members of the worldwide Sephardic community – descendants of Spanish Jews expelled after 1492 – to claim dual Spanish citizenship. The gesture accompanies a general surge of interest in Spain in all things Sephardic, which has, in turn, coloured the current celebrations to mark the quatercentenary of the death of Doménikos Theotokópoulos, or El Greco.

The Cretan-born painter has certainly fired Spain’s collective imagination. El Greco and Modern Painting, which recently opened at Madrid’s Museo del Prado, is attracting long queues. Earlier this year, a quarter of a million visitors saw another display of El Greco’s work in the painter’s adoptive city of Toledo, where smaller shows are set to run this autumn.

The location of one of these, in Toledo’s 14th-century Tránsito Synagogue, is appropriate, given the enduring intrigue around the painter’s origins. Was El Greco Jewish? All evidence suggests that he was raised a Greek Orthodox Christian. The novelist Félix Urabayen, however, was one of several early 20th-century Spanish writers convinced of El Greco’s Jewish (and possibly Sephardic) ancestry. “Semitic the city”, Urabayen wrote of Toledo, “and Semitic its painter.”

Under the 1939-75 dictatorship of General Franco, the painter’s soulful caballeros were held up as the essence of Spain. Part of the fascination in his art, in Urabayen’s day as now, seems to be the counter-narrative that El Greco invites. Jewish or not, he was undoubtedly an outsider: a liminal figure, who opens up new ways of seeing.

Having absorbed Venetian colour and Roman muscularity into the Byzantine style of his roots, “Il Greco” arrived in Spain in 1576, settling in Toledo. At the dusty, churchy heart of the Spanish empire, the city he painted into his biblical retellings is bathed in an eerie light, a place to which heaven sometimes swoops to reveal itself, as in his masterpiece “The Burial of the Count of Orgaz” (1586-88).

Although he actively helped brand the mysticism of Spain’s counter-reformation, the painter died a misfit in 1614. His books reveal far greater passion for architecture than for Christianity. His portraits of ecstatic biblical characters hint at a sympathy with outsiders and outcasts that chimes with modern sensibilities. Most curiously of all, his life in Toledo was apparently lived in warm proximity to Jewish conversos, at odds with the Inquisitional spirit of the times and its dismal crusade for “purity of blood”.

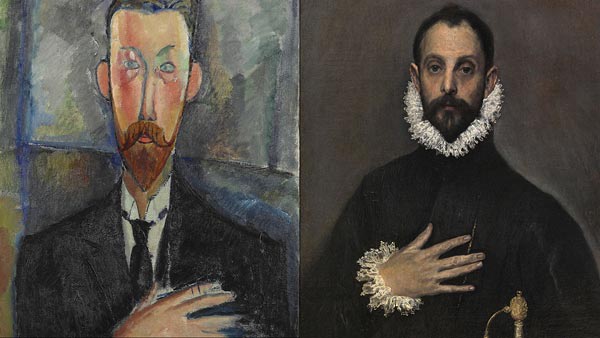

The Prado exhibition, El Greco and Modern Painting, is not, on the surface at least, about the Jews but about 20th-century artists’ admiration for him, and there is a wide array of work on display by Manet, Rivera, Bacon, and Pollock among many others. The rediscovery of El Greco in the late 1800s was prompted not just by his spiritual intensity but also by the solid, sculptural nature of his bodies. An 1890 version of “The Bathers” reveals the clear debt owed him by Cézanne. On seeing the naked forms in “The Vision of Saint John” (c1608), Picasso stumbled on a crucial formal solution for “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907).

“El Greco projected an idea of suffering that found a deep resonance with German expressionists,” says the exhibition’s co-curator, Javier Barón. Pictures here by Chagall, Jacob Steinhardt and Chaïm Soutine also attest to a similar resonance among 20th-century Jews – not just Jewish painters but critics such as Julius Meier-Graefe, Germany’s foremost champion of El Greco. Hung here, Lovis Corinth’s 1912 portrait of Meier-Graefe has transposed Greco-esque distortion into the modern anxiety that the Nazis so hated, and would later brand as degenerate.

In Toledo, the tributes to El Greco continue. Among the many treasures of the Tránsito Synagogue is the mudéjar plasterwork of its prayer hall, teeming with vegetable and geometric details. Against this backdrop, a painting by the German fluxus artist Wolf Vostell, “Shoah, 1492 to 1945”, is being displayed throughout the El Greco commemoration.

“Vostell lived in Spain during the Franco dictatorship,” says synagogue curator Alfredo Mateos. “Like El Greco, he was a stranger, an outsider in a time of state-imposed orthodoxy.”

Across Vostell’s long “Guernica”-style canvas, humanoid forms are crushed by a concrete block in the shape of a distorted cross. The dates in the painting’s title – 1492 to 1945 – Mateos observes, perturb many Spanish visitors. Some react indignantly to the link between the expulsion of Spain’s Jews and the Holocaust.

Dig deeper into the way different ages have responded to El Greco, Mateos says, and there are other revealing links to the marginalised and the shunned. In the 1920s, Spanish writer Gregorio Marañón argued that the bodies in El Greco’s apostle portraits were strangely attenuated because the painter used the insane as models. In an earlier hypothesis, Marañón suggested that El Greco had modelled the apostles on Toledo’s converted Jews.

Long before El Greco’s arrival, the city was a thriving centre of translation by Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars under Catholic King Alfonso X. That period is evoked in a permanent Artangel project, created for this year’s El Greco anniversary by sculptor Cristina Iglesias, and entitled “Tres Aguas” (Three Waters). In one of the sites remodelled by Iglesias, the paving stones of Plaza del Ayuntamiento have been taken up to “reveal” a stream below, flowing over gnarled roots.

Antonio Illán, an art critic for Spain’s ABC newspaper who has written extensively on the Jewish links to El Greco, has a special reason to feel stirred by the imagery of these roots. “Illán is an old Toledan name,” he says. “In Hebrew, it means tree.”

El Greco may not have been Jewish, Illán concedes, but it is remarkable how the painter’s closest colleagues, as well as his mistress and mother of his child, were Jewish converts. Pictorial oddities, such as one found in the “Allegory of the Camaldolese Order” (c1599), also intrigue Illán. “The vegetation in this picture takes the form of a Jewish menorah. It is one of various double readings that we find in El Greco’s work.”

Mateos agrees that part of the fascination in his art is discerning what lies under the surface: “We are still hearing this official discourse of El Greco as ‘the soul of Spain’, and I think people can see through that. Ordinary people can smell the heterodoxy in this painter.”

Back at the Prado, visitors have the chance to study Chagall’s Greco-influenced “Rabbi of Vitebsk” (1914). They can also contemplate the grief weighing down on David Bomberg’s 1955 self-portrait “Hear O Israel”, its inspiration drawn from El Greco’s “Christ Carrying the Cross”, and reflect that even in the particular anguish of the 20th century, Jewish painters could smell his heterodoxy too.

——————————————-

‘El Greco and Modern Painting’, Museo del Prado, Madrid, to October 5 www.museodelprado.es/en

‘Shoah’, Wolf Vostell, Sinagoga del Tránsito, Museo Sefardí de Toledo, to January 30 2015, museosefardi.mcu.es

Photographs: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence; Musée Beaux Arts; Museo del Prado

Comments