Game of talents: management lessons from top football coaches

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

At lunchtime on the day of the Champions League final in 2012, Chelsea’s manager Roberto Di Matteo had selected 10 of his 11 players. He just didn’t know who to play in left midfield. The player would have to combat Bayern Munich’s brilliant Arjen Robben and Philipp Lahm. Going into the last team meeting, Di Matteo had a private chat with his left-back, Ashley Cole. He outlined the situation, then asked Cole who he would play at left-midfield. Instead of naming a seasoned star, Cole said: “Ryan Bertrand.” The 22-year-old reserve Bertrand had never played in the Champions League, let alone in club football’s biggest game. “Why?” asked Di Matteo, surprised. “I trust him,” replied Cole. Bertrand played well, and Chelsea beat Bayern on penalties. In part, this was a victory for talent management. Di Matteo had put aside his ego, and let trust between two players drive the decision.

Talent management has been a business obsession at least since 1997, when the consultancy McKinsey identified a “war for talent”. The most visible battleground of this “war” is team sport. Football, in particular, is “the quintessential model for modern-day talent-dependent business”, writes Chris Brady, professor at Salford Business School. Big football clubs pay more than half their revenues to between 3 and 7 per cent of their workforce: the players. These young men are rich, multinational, mobile, often equipped with large egos and therefore hard to manage. Football managers are, above all, talent managers.

One of the writers of this article, Mike Forde, has watched football’s “war for talent” from up close. From 2007 to 2013, he was Chelsea’s director of football operations, dealing with all areas of performance and team operations. Now he consults sports teams, including the San Antonio Spurs, the American basketball champions. He has identified some sporting lessons for talent management.

1. Big talent usually comes with a big ego. Accept it

Carlos Queiroz, former coach of Real Madrid, says: “Top, top players have a profound awareness of their specialness, of their unique talent, that goes beyond arrogance — that just is.” Big talents know that their employers need them. This gives them scope to break rules of behaviour.

Conventional wisdom says egos damage an organisation. But good players succeed partly because of their egos: they are driven to be stars. In that same Champions League final of 2012, centre-forward Didier Drogba won the game by converting Chelsea’s crucial fifth penalty in the shoot-out. Four years previously, in the Champions League final in Moscow, Drogba had also been assigned the fifth penalty but hadn’t taken it because he was sent off just before the shoot-out.

In 2012 Forde asked him in the changing-room afterwards whether he had wanted to take the fifth kick. Drogba replied: “I only wanted to take the fifth penalty, after everything that happened in Moscow.” He saw himself at the centre of the drama, and wanted personal revenge. Contrary to cliché, there is an “I” in “team”.

If you only want to manage obedient soldiers, you will make your life simpler but you will have to forego difficult talents such as Drogba. That’s why Arsenal’s manager Arsène Wenger says: “If you want an easy week [in training with the players], then expect a hard weekend [in the game]. If you want an easy weekend, then prepare for a hard week.”

Former Chelsea coach Guus Hiddink believes managing difficult people is the best test of a manager. “No player is bigger than the club,” goes the sporting cliché, but a club should be big enough to accommodate any good player. When Hiddink managed PSV Eindhoven 25 years ago, his star was Romario. The Brazilian striker often stayed too long in Rio for carnival, lazed about in training, and skipped team meals. Hiddink exempted him from team discipline. That entailed defending him against the complaints of hardworking players. Romario understood the flip side of the deal: in matches, he had to perform. Romario was trouble but a good football team doesn’t need to be a harmonious place.

Perhaps Alex Ferguson’s greatest achievement in his 27 years managing Manchester United was keeping the supremely difficult Eric Cantona on board and performing from 1992 to 1997. The Frenchman joined United aged 26, having left most of his previous seven clubs in bad odour. Ferguson understood that the key to Cantona’s fairly simple personality was always to take his side, no matter how wrong he was — even when he infamously karate-kicked a spectator. Cantona repaid his protection.

2. Look for big egos that have ‘got over themselves’

That’s what San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich says. Some players underperform early in their careers because they are immature. They lack discipline, commitment or listening skills. However, most athletes grow up. Often the prompt is reaching a certain age, starting a family, or experiencing failure. That’s the point when, in Popovich’s terms, they “get over themselves”. Then they accept their limits, and become coachable, open to hearing a message such as: “There might be a better way to look after your body.”

3. Single out and praise those who make sacrifices for the organisation

Boudewijn Zenden, a Dutch player whose clubs included Barcelona and Chelsea, says: “Football is the most individual team sport. At least, you can experience it that way. In the end it’s each man for himself.”

This means that the talent wants glory for himself, not just for the organisation. Every player hopes to star in his own preferred role. Zenden recalls that at Euro 2000, both he and Marc Overmars wanted to play left wing for Holland. Overmars practically refused to play right wing.

In the opening match against Denmark, Holland’s coach Frank Rijkaard let Overmars start on the left wing. Zenden reluctantly agreed to play on the right, for the team’s sake. In the first half, he recalls: “I played the worst 45 minutes of all time.” With a substitute ready to come on, Zenden was sure he would be taken off. Instead, to his delight, Rijkaard took off Overmars and moved Zenden to the left wing. Zenden recalls: “I had one assist and one goal and we won 3-0. The rest of the Euros, I played on the left.” By rewarding Zenden’s sacrifice, Rijkaard was encouraging others to make a sacrifice too.

4. The manager shouldn’t aspire to dominate the talent

Talent wins matches. The best talent now sits side by side with the owner, and sometimes takes the wheel from the manager. Successful managers accept this. They don’t try to emphasise their leadership by dominating the talent.

Pep Guardiola at Bayern Munich, for instance, avoids intruding in the changing room, which he considers the players’ territory. He “only ever goes into the dressing room during the half-time break”, writes Martí Perarnau in Pep Confidential, his intimate account of Guardiola’s first season at the club.

Football managers are traditionally compared with generals but today they are more like film directors — cajoling rather than commanding. Even Ferguson, who sought control, accepted when he couldn’t have it. In 2010 his best player, Wayne Rooney, publicly threatened to leave United for higher pay at neighbours Manchester City. Ferguson was miffed but he needed Rooney, so he raised his salary and let him back into the fold. The manager’s job is to win matches, not ego clashes. The key concept here is servant leadership.

5. Ask the talent for advice — but only for advice

That’s what Di Matteo did with Cole in 2012. Similarly, in 2010, Chelsea’s then manager Carlo Ancelotti picked his team for the FA Cup final against Portsmouth but then let the players devise the match strategy.

As he had expected, they opted for more or less the strategy he had used all season. But, still, why give the players such responsibility for a crucial game? Ancelotti says: “I was sure the players followed the strategy, because they made the strategy. Sometimes I make the strategy but you don’t know if the players really understand the strategy. Sometimes I joke with the players, ‘Did you understand the strategy?’ ‘Yes, yes!’ ‘Repeat, please!’” Chelsea beat Portsmouth 1-0 to complete the club’s first ever “double” of league and cup.

Ancelotti had empowered the talent. David Brailsford, general manager of cycling’s Team Sky, says: “We all perform better if we have a degree of ownership of what we do. Generally, we don’t like to be told what to do.”

However, the final decision on strategy should be the manager’s. After all, he ought to be the person who has thought about it hardest. Before Bayern hosted Real Madrid in last season’s Champions League semi-final, Bayern’s players persuaded Guardiola to play a 4-2-4 formation. Bayern lost 0-4. “I spent the whole season refusing to use a 4-2-4,” Guardiola lamented to Perarnau afterwards. “And I decide to do it tonight, the most important night of the year. A complete f***-up.”

6. The manager’s job isn’t to motivate

Good talent motivates itself. The comedian Peter Cook used to play a football manager who, in a mournful northern English accent, revealed the secrets of his trade: “Motivation, motivation, motivation! The three Ms.” Motivation remains an obsession of the sports media. The notion is that the player is an inert child, into whom the manager infuses motivation, ideally through a Churchillian prematch speech.

However, that’s not how top-level sport works. Over espresso at Chelsea’s training ground one afternoon, Ancelotti asked Forde what he had learnt after joining Chelsea from smaller Bolton in 2007. Forde said that at Bolton, every four or five games, the staff had to sit the players down and remind them of the basics: winning, good behaviour, professionalism. But, in Forde’s first six months at Chelsea, no coach had had that conversation with the players. Ancelotti smiled and said: “Mike, our job is not to motivate the players. Our job is not to demotivate them by not providing the challenges and goals that their talents need.” A big talent is usually self-motivated. He wants to succeed for himself and his career. However, if he senses that the management is second rate, he may decide to go and succeed in another organisation.

Brailsford agrees: “Motivation has not really got much of a place in sport.” You win the Tour de France, he explains, by going out to train on rainy mornings when you aren’t the slightest bit motivated. Rather than motivation, Brailsford emphasises long-term commitment: sustained motivation over time.

Before a big match, players don’t need motivating. More likely, they need to be relaxed. That’s why Nottingham Forest’s great manager Brian Clough sometimes distributed beers on the bus to games (something no longer considered best nutritional practice). Often Clough’s last words to the players in the changing room were: “Go out there and enjoy yourselves.”

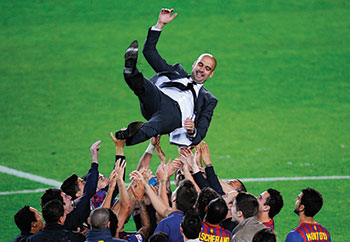

Guardiola, reflecting on his departure from Barcelona, says: “What happened at Barça is not that I failed to motivate them. No, I failed to seduce them!” A manager motivating players is a top-down relationship, whereas seduction implies a relationship of equals.

7. The talent needs to trust each other more than it needs to trust the manager

In a crucial game or business pitch, the key relationship of trust is between the people who have to work together. They don’t have to like each other. At Manchester United in the 1990s, strikers Teddy Sheringham and Andy Cole loathed one another. But each trusted the other’s talent.

8. Improve the talent

Often in an organisation, a manager spends most of his energy managing incompetent people, because they cause the most problems. The manager might be up all night rewriting a bad report. Meanwhile, talent that is performing well tends to get left alone.

That’s a missed opportunity, because talented people usually have a gift for learning and a desire to improve. That desire often drives their career choices. The talent probably joined your organisation because he or she thinks they can improve there. If the manager shows he cares about the talent’s career by helping the talent improve, the talent will develop trust in the manager. (In football, trust is rarely given up front but has to be earned over time.)

Good managers create a learning culture in which players can improve. Wenger, for one, often brings out qualities in players that they hadn’t known they possessed. He turned the inconsistent winger Thierry Henry into a brilliant striker, the midfielder Lilian Thuram into a defender, and the defender Emmanuel Petit into a midfielder. A student of autobiographies, Wenger believes that greatness ensues only when a talent meets someone “who taps him on the shoulder and says, ‘I believe in you!’”

Chelsea’s manager José Mourinho is Wenger’s nemesis but shares his urge to develop talent. One day after a training session soon after Mourinho first joined Chelsea in 2004, Frank Lampard emerged naked from the showers. Suddenly, Mourinho popped up and looked him meaningfully in the eye.

“All right, boss?” asked Lampard.

“You are the best player in the world,” replied Mourinho.

The naked footballer didn’t know what to say.

“You,” continued Mourinho, “are the best player in the world. But now you need to prove it and win trophies. You understand?”

He was signalling to Lampard that they were starting a programme of individual improvement — in business jargon, a project to go from good to great. Today Mourinho seems to be engaged in a similar project with Eden Hazard, who was recently named the Premier League’s player of the season by his peers.

Guardiola, too, devotes lots of energy to transforming players who are already performing. One evening in 2009, watching video of Barcelona’s rivals Real Madrid, he noticed a large space between their central defenders and midfielders. He rang his winger Lionel Messi: “Leo, it’s Pep. I’ve just seen something important. Really important. Why don’t you come over?” Messi arrived 30 minutes later. Guardiola played the video and showed him the space. That was where he wanted Messi to play. That evening began Messi’s transformation from winger to withdrawn centre-forward, or “false nine”. In that role, Messi became the world’s dominant footballer.

However, transforming a talent only works if the talent wants to change. Perarnau writes: “When a player says enough is enough, when his determination to improve falters, when he stops believing in his own ability to progress or abandons the idea altogether, then [Guardiola] throws in the towel too. It’s over.”

9. 99 per cent of recruitment is about who you don’t sign

Be fearful of recruiting new talent, because an organisation is a fragile thing. Guardiola compares a team to a glass bottle hanging from a thread. Introducing a weak or undisciplined player can damage the team’s standards and culture. Then the best talent will leave.

In January 2008 Chelsea had a chance to sign the Brazilian forward Adriano from Inter Milan. Brilliant and strong, he seemed the perfect signing. But, as Chelsea researched his lifestyle, the club came to doubt his discipline. He could damage Chelsea. The club didn’t sign him. Indeed, his career soon went off the rails.

Often, an organisation doesn’t need to recruit because the talent is on its books already, adjusted to the organisation and steeped in its culture. At Barcelona in 2008 Guardiola gave the unrated homegrown teenager Pedro a chance. Two years later, Pedro won the World Cup with Spain.

10. Accept that the talent will eventually leave

When Nicolas Anelka joined Bolton in 2006, it was the smallest club on his CV. His career path wasn’t matching his talent. Bolton offered him a four-year contract. However, during contract talks, the club’s manager Sam Allardyce and Mike Forde told Anelka they only expected him to stay two years. The confused player leafed through his contract, looking for a break clause that he might have missed. The Bolton men reassured him: there was no break clause. But if he fulfilled his potential by scoring 40 goals in two seasons, a bigger club would snap him up. Instantly, Anelka had a target at Bolton: a pathway to a better club. He shone for Bolton and, in January 2008, moved up to Chelsea.

Few highly talented people are looking for a job for life. The average graduate changes jobs 11 times in his/her career. The average elite footballer changes club 3.8 times. Big talents won’t “die for the shirt”. Your organisation is just a vehicle for their talents. They join it to work with each other, not for you. If they can go somewhere better, you probably won’t manage to block them. To quote business scholars Deepak Somaya and Ian Williamson: “The ‘war for talent’ is over . . . talent has won!”

The manager’s response should be to seek productivity, not loyalty. A good manager keeps the talent on board as long as possible, meanwhile preparing for the talent’s exit. Ferguson at Manchester United pursued a policy of early replacement: “An internal voice would always ask, ‘When’s he going to leave, how long will he last?’ Experience taught me to stockpile young players in important positions.”

11. Gauge the moment when a talent reaches his peak

On average, footballers peak at about age 28. That’s when they have an old head on legs that are still young. However, each player’s trajectory is unique. When Frank Arnesen was Chelsea’s technical director, he used to ask: “When is a player 28?” In other words, when will he peak? In Chelsea’s view, the peak typically comes after about 300 matches, seven seasons, three clubs, one big success and one failure.

Once a player has peaked, he is a melting ice block. The wear is mental as well as physical. Few people can sustain the concentration necessary for top-level sport beyond a few years. Guardiola’s friend Garry Kasparov, the chess player, told him over dinner in New York: “The minute I won my second world championship in 1986, I knew who would beat me in the end.” “Who?” asked Guardiola. “Time,” replied Kasparov.

Kevin Roberts, executive chairman of advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi, suggests that today Chelsea’s question should be: “When is a player 26?” Roberts thinks that talent is emerging younger and burning out faster, because of demanding travel schedules and the “24/7 attention economy”. The trick is to replace the talent before he is just a puddle of water on the floor.

Simon Kuper is an FT Weekend Magazine columnist.

Mike Forde is a talent management consultant.

Photographs: AFP; Getty

Comments