Col Needham of IMDb: ‘Everything about me is movies’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It was going to be a great flight. Here’s why: the British Airways entertainment system had come on a few minutes earlier than usual and it was going to stay on a little longer. This meant that Col Needham, the founder and chief executive of IMDb, the world’s biggest movie database, had a shot at watching five films on the 10-hour flight from London to Seattle, rather than his usual four.

This was in January. Needham was on his way to the Sundance Film Festival. As the airliner looped over the Atlantic, he watched Tour de Force, a French cycling comedy (Needham is learning French) and gave it an 8 out of 10 on his IMDb ratings page. Mid-ocean, Needham followed up with the animated food adventure Cloudy with A Chance of Meatballs 2 and awarded it a 7. Then came Austenland (6) and last year’s Proclaimers musical, Sunshine on Leith (7). Somewhere over the Midwest, Needham sensed that time was against him, so he went for Filth, starring James McAvoy as an alcoholic policeman, because he had seen it before and it has a short running time of 97 minutes. “Just as they said, ‘We’re closing down the entertainment system,’” he recalled, his voice filled with the joy of it, “the end credits were rolling.” Needham gave Filth a 7.

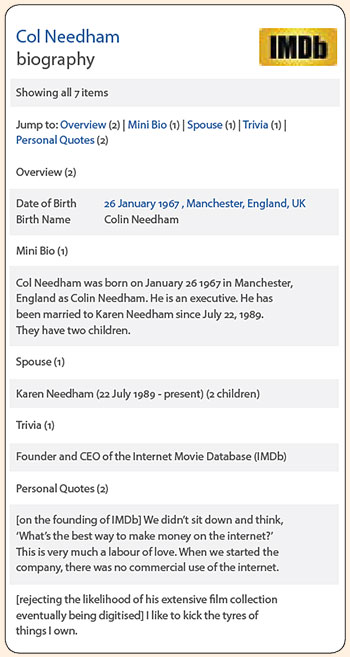

I learnt all this recently in the kitchen of Needham’s house, which is on the northern edge of Bristol. We were standing by the back door on a morning of torrential rain. Gap-toothed, shorn-headed and quick to giggle, Needham was leaning against the counter, thumbing his iPhone. He was on his IMDb page, which that day listed 8,505 films that he had seen and ranked – approximately one for every 48 hours that he has been alive since January 26 1967.

“I don’t need to remember anything,” he mused. And then his voice switched register: “Remember the necklace.” Needham said this in a different tone because it is a quote from Vertigo, which is his favourite film. We looked at the weather. It was too wet to take his picture. When the photographer left to come back another day, Needham called out: “‘See you next Wednesday,’ as they say in the John Landis films!” Which is a reference to the American comedy director John Landis, who always included the phrase in his movies as a homage to Stanley Kubrick because it is a quote from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Needham had apologised almost as soon as I arrived. We were in his home cinema and he had just done a line from Armageddon – “I don’t want you to miss a thing” – about my tape recorder. “Sorry,” he said. “Everything about me is movies.” And it is, to an inseparable extent. Needham’s life, obsession and IMDb, the machine he has built to manifest it, are so deeply enmeshed that they can no longer be pulled apart.

In 1990, Needham was a shy, Hitchcock-obsessed computer programmer who uploaded his personal movie database on to an internet bulletin board. They were simple records, kept on a succession of early computers, of every film he had seen since the age of 13. This became the Internet Movie Database, or IMDb, which is now one of the world’s most popular websites. About 190 million people visit every month to pore over the careers of movie stars and get lost in its welter of information about the entertainment business. In 2013 alone, IMDb added 350,000 movie and TV show titles – the equivalent of 17 editions of Halliwell’s, the old movie encyclopedia. In a quarter of a century, Needham’s teenage catalogue has become Hollywood’s hard drive, and the movie-goer’s answer to the eternal question: “Is that the guy who was in that thing?”

More than that, IMDb is also a symbol of the changing value of data. What began as trivia could soon be integral to the process of making movies itself. IMDb was bought by Amazon in 1998 (the price has never been disclosed), right at the beginning of the internet giant’s quest to understand the world’s consumer habits and sell us what we want. Now IMDb and Amazon are part of a changing Hollywood, trying to use our clicks, our comments, our ratings – even our ideas – to create the next billion-dollar franchise, the next Breaking Bad.

And Needham has been there, the database guy, at every unlikely step. He squirms with pleasure when he talks about it. He walked his first red carpet, in Cannes, in 2008, and regularly appears on industry “power” lists. When we met, he was just about to enter the hectic weeks of the awards season: the Baftas; and then the Oscars, where he has been a guest for the past two years. He went bashful when I asked if that made him a bona fide Hollywood player: “Well, I guess . . .”

It was later that day. We were sitting at a rickety table in IMDb’s scruffy offices in Bristol. There was a poster from the crime thriller Narrow Margin on the wall. In fairness, it didn’t feel very glamorous. But Needham isn’t like that. Until 2011, he ran IMDb from home. The website has between 100 and 200 staff, split between Bristol and offices in Seattle and Los Angeles. He still gets up at 6am, seven days a week. On weekends, that is in order to watch movies before his wife wakes up. “I’ve already watched a film before Karen is out of bed, easily.”

He grew up in Denton, a former hat-making suburb of Manchester. As a boy, Needham spent a lot of time with his grandparents, who ran a newsagents, and, in the late 1970s, the alchemy of computers and movies began to stir in his brain. He read Personal Computer World magazine, and built his first machine from a kit, a Science of Cambridge MK14, at the age of 12. He saw Star Wars and Colossus: the Forbin Project, which is about a computer that takes over the running of the US defence system. He took out Alien and watched it 14 nights in a row. He typed out information about every film he had seen. “Technology and film,” he explained, “these two things were kind of on this collision course.”

IMDb grew out of a collective effort, led by Needham, to organise movie trivia that was being posted to the early internet. At the time, he had just moved to Bristol, where he was working for Hewlett-Packard on artificial intelligence, having studied computer science at Leeds. On October 17 1990, he found a way to upload his personal movie database – a complete record of every film he had seen since January 1 1980 – on to an online bulletin board. “Get this for a mouthful: it was the ‘Rec.arts.movies Movie Database Script Package.’” And for the next six years, that was Needham’s Saturday mornings. He was the unofficial leader of a band of about 20 movie and computing brethren, administering lists on a discussion system called Usenet, before taking his twin daughters to the park. “It was our hobby,” he said. “I was a film buff that ran this international volunteer organisation of other film and TV people.”

By 1993, the first IMDb website was running on spare capacity at the University of Cardiff’s web server. Two years later, with traffic and data doubling every two weeks, the group decided to form a company and sell advertising. Needham was the largest, but not a majority, shareholder. IMDb.com launched at the Oscars the following year. He quit Hewlett-Packard and was the database’s first and, for a time, only employee.

It will be 25 years, next year, since Needham first shared his database. And like other huge collaborative projects on the web such as Wikipedia, IMDb retains the nerdy germs that got it going in the first place. Hundreds of thousands of people – from actors polishing their credits, to film-makers listing their crew, to latter-day Col Needhams – post information on IMDb. Everything is filtered through algorithms that score a contributor’s previous reliability, before being checked by an IMDb employee. “For every account we know exactly what you have submitted before,” said Needham. “We can see, you are really, really reliable on 1940s Westerns but not so great on 1960s French film.”

The result now functions for some as Hollywood’s memory. And that means IMDb has great power. Not necessarily in a very active or intrusive sense but in more of a utility sense, like Los Angeles’ electricity or water supply. “I can remember life before IMDb,” Richard Hicks, the casting director of Gravity and Zero Dark Thirty told me. “It was a Kafkaesque assemblage of file cabinets and Rolodex cards and scrawled notes on the backs of pictures and résumés.” When the site went down for a couple of hours for maintenance recently, Hicks simply stopped working.

…

IMDb stopped being simply a fan site in 2002, when it launched IMDb Pro. The premium service costs $124.95 a year and offers industry professionals contact information, a chance to post their CVs and summaries of about 12,000 projects in production, so they can see who’s making what. (As with other financial information, such as the site’s earnings, IMDb will not say how many paying subscribers it has.) In 2008, IMDb acquired Withoutabox.com, the main submissions service for independent film festivals, meaning that it now provides critical infrastructure to that part of the movie business as well. Withoutabox acts as a marketplace for festival organisers and film-makers, allowing independents to submit the same film to, say, 20 festivals at once, rather than laboriously supplying 20 separate submissions.

The power and the reach mean, perhaps inevitably, that IMDb has faced disputes. Last year, it won a court case brought by an actress called Junie Hoang, who contended that by publishing her real date of birth, in 1971 (as opposed to her given date of birth, in 1978), the site had cost her $1m in lost earnings. Hoang accused IMDb of using data she supplied when setting up her account to find out her age, alleging “breach of contract”. She has appealed against the court case result. Needham would not comment on the case but he rejected the idea that by making certain information public IMDb had the power to hurt people’s careers. “We do not delete accurate data,” he told me. “We provide everybody with the most information possible to make an informed choice.”

That extraordinary quantity of information is also what points to more intriguing questions about IMDb’s future. As part of Amazon, the site, in Needham’s phrase, has “access to all of their clever personalisation algorithms” – which means that IMDb suggests other films and movie stars for you to look up when browsing. The data cuts both ways. After almost 25 years, and with the best part of 200 million people crawling through its pages each month, IMDb has an unparalleled map of how we, the watching audience, interact with what we see on our screens. Who we look up. What we comment on. The genres that we adore. The digital ingredients, if you can read the signs right, of a hit.

There are already indications of convergence under way between IMDb and the Hollywood machine, between Needham’s catalogue and the industry he idolises. In the US, you can click on a film on IMDb and start watching it through Amazon Instant Video (last month this became available to Amazon Prime customers in the UK). And in 2010, Amazon began to produce films and TV itself. The emphasis is on letting the crowd – manifested as clicks, comments, scripts, sitcom situations – submit ideas and then determine which projects get green-lit or not. So far 18,000 movie ideas and 4,000 TV proposals have been sent in, and Amazon Studios released its second season of five TV pilots last month. Roy Price, the director of the studio, described the project to me as a “part of a broader technology-enabled cultural shift” to make film-making more democratic. “IMDb as a platform can be part of that,” he said.

It’s enough to make some movie lovers pause. The idea of making creative decisions via the crowd, even if it is the largest and most digitally integrated crowd ever assembled, can be anathema. That is why Needham’s personality, his unguarded obsession, still matters. “When you engage with IMDb, you feel the fandom,” Keri Putnam, the director of the Sundance Film Festival, told me. “Col doesn’t feel like someone who has come from a technology field to try and change Hollywood.”

Anything but. Until recently, when he wanted to be vague, Needham told people that he ran a website. Nowadays, he confided with quiet delight, he says he works in the film business. A few days after we met, I saw him in the thick of it, standing in a constellation of movie stars at the Bafta awards dinner at the Grosvenor House Hotel, in Mayfair. Needham and his wife were in evening dress, wearing gold IMDb badges. Bradley Cooper was nearby, taking selfies; Dame Helen Mirren was kissing congratulations to Alfonso Cuarón, the director of Gravity; Cate Blanchett went past like a ship under sail.

I asked Needham if it was possible for him to stand in this room and not just see everybody’s IMDb profile. “Sometimes,” he said. Then he broke off. “There’s Bruce Dern,” he said, pointing at the white-haired star of Nebraska, passing our table. “He was in the last scene in Family Plot, the last film ever directed by Alfred Hitchcock.” Needham shrugged happily. “Sometimes I do struggle though. Sometimes I don’t know everybody.” He paused. “That’s why we’ve got the app.”

——————————————-

IMDb in figures

190 million: visitors each month

350,000: movie and TV titles added in 2013

1998: IMDb bought by Amazon

2002: launched IMDb Pro

2008: acquired Withoutabox.com

To comment on this article please post below, or email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments