European unicorns remain elusive

Simply sign up to the European companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Skyscanner, the British flight-search website, raised £128m in financing in January, it joined an elusive club: European unicorns.

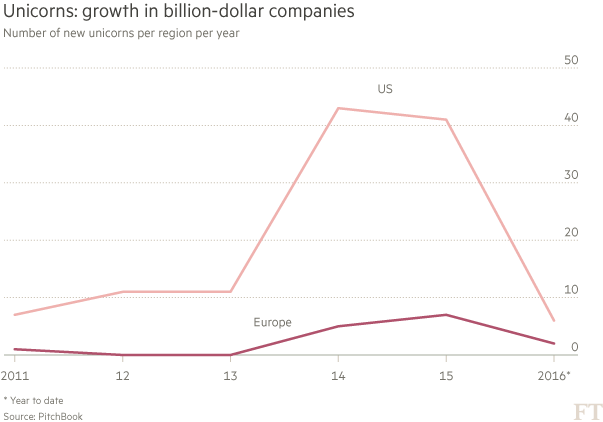

Since then, just one other European company has managed to become a unicorn, as private start-up companies with valuations of at least $1bn are called, according to PitchBook, a database of venture capital and merger and acquisition deals.

That equates to one new unicorn every 2.5 months, compared with one every 1.7 months last year, signalling that investors are becoming more wary of investing in big tech start-ups in Europe.

The reluctance to back these companies comes amid concerns about the soaring valuations of private start-ups globally. Recently, many investors were forced to write down investments, including those in Dropbox, the file storage website, and Snapchat, the social media platform where pictures disappear.

But venture capitalists and asset managers invested in fledging tech businesses say the reticence in Europe is unwarranted, arguing there is little sign in the region of the overheating North America has experienced.

Siraj Khaliq, an investment partner at Atomico, the European venture capital fund founded by Niklas Zennström, the co-founder of Skype, the online telephony group, says valuations for companies in Europe are much more conservative than in the US.

“We are seeing such great companies [in Europe] that we actually have to pace ourselves. We are seeing so many opportunities,” says Mr Khaliq, who set up one of the world’s first unicorns, an agri-tech business called The Climate Corporation.

Tim Hames, director-general of the British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association, the industry body, adds: “The consensus remains that European valuations, while high, [are] not wild and still look more sober than their US counterparts.”

In the US, valuations rose as investors piled into private start-ups in a bid to take advantage of the boom in technology companies.

Many of the best-known start-ups of recent years have opted to stay private rather than have an initial public offering, forcing investors that wanted access to these tech companies to invest privately.

Investment came not just from the traditional backers of young companies — the likes of venture capitalists and private equity firms. Mutual fund managers also dipped their toe into the market, including BlackRock, T Rowe Price and Fidelity Management and Research.

These traditional asset managers typically were interested in providing financing to so-called later-stage companies, businesses that already have products or services that are commercially available and that can show significant revenue growth.

According to PitchBook, the median valuation for these companies in the US has increased twofold to $60.6m since 2010.

It is not just large start-ups where valuations have increased on the back of growing interest. Early-stage companies in the US that are ready to operate but have yet to begin commercial sales had a median valuation of $8.9m in 2010. By 2016, this number had soared to $22m.

In Europe, these numbers are much smaller: early-stage companies have a median valuation of $8m currently, while later-stage companies are worth $21m.

The lower valuations in Europe are partly due to the fact that there is less money available to invest in start-ups, says Mr Khaliq, who adds that there is 14 times more capital in venture capital funds aimed at later-stage financing in the US than in Europe.

European investors also tend to be more conservative when it comes to investing in start-up companies, says Manish Madhvani, co-founder and managing partner of GP Bullhound, an investment bank.

When European investors invest in a start-up, they like to see strong revenues and the opportunity for these to grow further, he says. In the US, in contrast, revenues have often tended to be lower, despite the high valuations.

This has lead some to predict that a tech bubble is emerging in the US that could lead to unicorpses — dead unicorns.

Mr Madhvani says: “The US did reach levels of excess that were much too high in terms of valuations. In Europe, because the pool of capital is less, the bar was higher and the valuations, for the most part, tended to be lower.”

But there are few traditional asset managers that invest in tech start-ups in Europe.

The rare exceptions include Baillie Gifford, the Edinburg-based fund house with £123bn in assets under management, and Artemis, the Scottish manager. Both invested in Skyscanner in January.

Baillie Gifford has also backed several other unicorns, including Spotify, the music-streaming app, HelloFresh, the food-delivery start-up, and Anaplan, the software company.

Matthew Wong, research analyst at CB Insights, a venture capital database, says Europe’s private companies face a tougher challenge than their counterparts in the US and Asia when it comes to raising money.

“We have seen several prominent asset managers, including BlackRock and Temasek [the Singaporean state investment company], invest in European unicorns, but not to [the same] degree as in the US and Asia,” he adds.

Mr Khaliq expects fund managers’ interest in European unicorns to rise, because they risk missing out on some of the fastest-growing businesses in the region if they continue to shun private companies.

“At the end of the day we are going to see more and more money going into private companies, because there are more and more large private companies,” he says. “Historically, these companies would have listed, but now they don’t need to do this to raise money.”

Mr Madhvani agrees: “[Traditional] asset managers will have to figure out how to get access to those companies.”

Some investors were spooked by the negative stories surrounding unicorns at the start of the year, but these concerns are now lessening for European companies, he says.

“European unicorns are unlikely to come under the same pressure [as their US counterparts], because they are more advanced in terms of [the] revenues [they generate].

“I would expect more of the European start-ups to stay around. In the US, we would expect more failures.”

There are signs that some investors agree with his views. Figures provided by Atomico, using data from Tech.eu/Dealroom, the industry websites, show there were 125 series-A (early-stage) funding rounds where investors provided capital during the first five months of this year, compared with 105 during the first half of 2016.

Many asset managers, however, remain reluctant to invest, because of concerns about the outlook for unlisted tech companies. Even seasoned investors in unicorns are hesitant. Andy Boyd, head of global equity capital markets at Fidelity, says because each company is unique, it is difficult to say whether overall valuations in the marketplace are too high.

“Fidelity looks at hundreds of deals each year and we still see attractive opportunities in Europe and the US, but sometimes we can’t agree on price,” he says.

Walter Price, who manages the Allianz Technology Trust for Allianz Global Investors, the €435bn asset manager, also argues that valuations for unicorns are “too high relative to public comparable [businesses], and investors are no longer enthusiastic about companies that are losing money”.

Andy Evans, manager of the Equity Value fund at Schroders, the UK’s largest listed fund house, has big concerns about the valuations of Europe’s tech start-ups.

“People invest in unicorns on the assumption they will find the next Google or Facebook. But in a basket of unicorns, it is highly likely there will be far more lastminute.coms [which was valued highly, but suffered a precipitous fall in its share price after listing] than Facebooks,” he says. “Unicorn valuations, in many cases, are a triumph of hope over reality.”

Comments