How millennials’ taste for ‘authenticity’ is disrupting powerful food brands

Simply sign up to the US & Canadian companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Ben Branson asked a waitress for a “mocktail” one sober Monday night, “she came back with this pink blend of juice”, says the 35-year-old, wincing. “I felt like an idiot. I thought — I can’t be the only person not drinking alcohol on a Monday who isn’t satisfied with a blend of fruit juices.”

Spurred by the pink juice experience, he came up with the idea for Seedlip, a non-alcoholic drink for grown-ups, inspired by a 17th-century herbal medicine book, The Art of Distillation.

Mr Branson’s father was a brand designer and his mother’s family have farmed for 300 years. Peas from their farm, along with hay, rosemary and thyme are the main ingredients in Seedlip which, despite the lack of alcohol, costs as much as an upmarket gin at roughly £27 a bottle. It is too bitter to drink neat and even mixed with tonic is best sipped rather than gulped.

Despite the price, Seedlip sold out within two days of its 2015 launch at Selfridges, the upmarket London department store. Three years later, it is still one of the store’s best-selling drinks. “I think that’s pretty remarkable,” says Mr Branson, gazing into his mint-green Seedlip cocktail in a Spitalfields bar in London’s now hip East End.

Even more remarkable is the fact that Diageo, the world’s biggest drinks company, decided in 2016 to invest in Mr Branson’s non-alcoholic venture. Seedlip is served in Michelin-starred restaurants and now sold in 17 countries.

Why millennials are seeking ‘authenticity’

A wind of change is ripping through the consumer industries. For decades, big meant better, consumers trusted brands they knew and convenience food was a novelty. No longer.

Emmanuel Faber, chief executive of Danone, France’s biggest food group, summed it up at the CAGNY industry conference in February this year. “Consumers are looking to ‘pierce the corporate veil’ in our industry and to look at what’s behind the brand,” he declared. “The guys responsible for this are the millennials.” Millennials have a completely new set of values, he said. “They want committed brands with authentic products. Natural, simpler, more local and if possible small, as small as you can.”

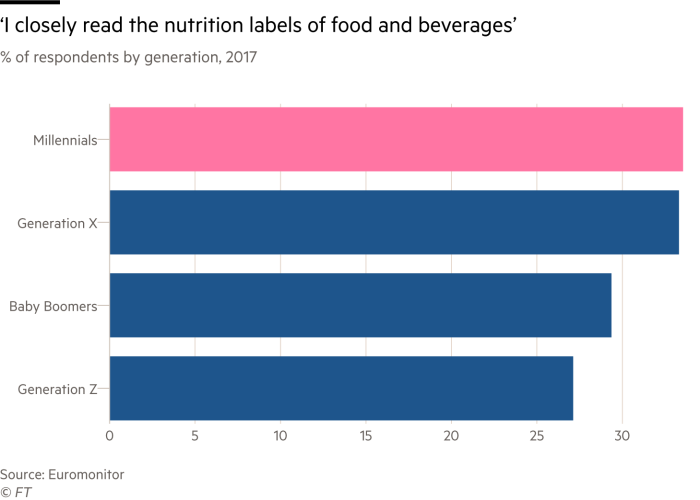

Millennial consumers — those aged 22 to 37-years-old, according to Pew Research — are in general more health-conscious than their parents were at the same age. They are drinking less alcohol, at least in developed markets. They want to know what is in the products they buy and where they come from, demanding curbs on plastic and waste. They are more environmentally aware — 61 per cent feel they can make a difference to the world through their choices, according to Euromonitor — and their trust in politicians and institutions is low. For big brands it all means increasing pressure, as this generation of consumers seeks “authenticity”.

Andrew Geoghegan, Diageo’s global consumer planning director, is very aware of the shift. “Authenticity is a huge trend,” he says. “We saw it coming through in the last 15 years in areas like craft beer.”

Michael Ward, Diageo head of innovation, adds that: “Consumers are increasingly aware of what they’re putting in their bodies, and making very decided choices about ingredients.”

Diageo is uncomfortable about making sweeping statements about the world’s 2bn millennials. “So-called millennials are really different across the world,” says Mr Geoghegan. He prefers to break down the way people drink into “occasions” rather than segment them by age. Seedlip fits nicely into the occasion for having “a really interesting drink but without any of the alcohol and calories”.

Mark Schneider, chief executive of Nestlé (the world’s biggest food group) agrees “it’s not only about millennials”, but regards their impact as hugely significant. “They’re important because this is a group that’s fast approaching their peak earning years. And youth rarely goes out of fashion. So whatever the millennials do, you can count on their preferences getting picked up by other generations and getting emulated. Catering to their needs is very important for any fast-moving consumer goods company,” he told investors recently.

Big brands are losing out to smaller companies

One of those preferences, certainly for millennials who can afford it, is food that is healthy, fresher and has natural ingredients. Sales of food claiming to be organic grew 10 per cent last year in the US, according to Nielsen, the market research group. Even in the weight loss industry, “everybody is talking about health and wellness. Nobody wants to use the word diet”, Mindy Grossman, chief executive of Weight Watchers, told analysts.

In this climate, big brands are losing out to smaller companies. Over the past decade, as big companies were still adding sugar and artificial colours to their processed foods, small start-ups sprung up offering healthier or more exciting alternatives, often with an interesting back story about their entrepreneurial owners.

Supermarkets are now devoting more space to small brands, which can also bypass stores altogether by selling direct to the consumer. Between 2011 to 2016, large brands in the US lost 3 percentage points of market share to smaller companies, according to Boston Consulting Group, equating to $22bn of sales.

“This is the first time we’ve seen this in 50 years,” said Jim Brennan, partner at BCG, in an interview last month with Bernstein Research. “It fundamentally challenges what maintains the consumer packaged goods industry, at least certainly in the western world, since the postwar period.”

Halo-Top ice cream, Graze snacks, Kind snack bars, Dollar Shave Club and Harry’s in razors, Tito’s in vodka, Fevertree tonics, The Ordinary and Glossier in skincare/cosmetics are all challenger brands that have grown rapidly, helped by authenticity credentials.

How social media is eroding barriers

Driving the change, even more than the buying habits of millennial consumers, is the rise of digital technology. In the past, a company needed a huge marketing budget to advertise on television and had to be big enough to persuade large grocery stores to stock its products. Those barriers have been eroded by social media, itself dominated by millennials, and online selling. As Mr Schneider says: “Because of digital change, once you have the product then making it to market has become cheaper and much faster. Initially, I think all large companies ignored that trend.”

The upshot is that big companies’ revenues are no longer growing as fast as they once did.

In 2011, the 50 biggest consumer groups — including Procter & Gamble, Unilever, PepsiCo and General Mills — were growing at an average of 7 per cent, according to the consultancy OC&C. But that rate has dropped every year since, and in 2016 average sales actually fell.

Jorge Paulo Lemann, the Brazilian investor behind both AB InBev and 3G Capital, which part-owns Kraft Heinz foods, told the Milken Institute conference in April that he felt like “a dinosaur”. “I’ve been living in this cosy world of old brands, big volumes, nothing changing very much,” he said. “You can just focus on being efficient and you’ll do OK. And, all of a sudden, we’re being disrupted in all ways.”

The industry is now at a turning point. Big brands still dominate. But with small being the new big, can they appeal to fussy consumers in fragmenting markets, while operating in an unfamiliar world in which Facebook “likes” can count for more than million-dollar marketing budgets?

“My biggest fear for this company, of which I have very few, is that we lose the connection with millennials,” Paul Polman, Unilever chief executive told the FT in November: “Very selfishly, because then obviously we don’t have future consumers any more.”

The new strategies happening now

Big consumer groups are still trying to work it out with a range of strategies, from buying up small on-trend start-ups, to cutting costs and increasing the rate of new products.

“They can’t make up their minds on how to respond,” says Nick Fereday, analyst at Rabobank, “whether the days of global iconic brands are over, or whether iconic brands are infinitely malleable and can be adapted to today’s trends.”

Faced with these challenges, the initial reaction has been to cut costs. This has also been driven by the enormous influence of 3G Capital, which has boosted profitability in its companies Burger King and Kraft Heinz through cost-cutting and big M&A.

P&G, the biggest consumer goods group in the US, has been shrinking its business by reducing its brands from 170 to 65 since 2015. The producer of Pampers nappies and Crest toothpaste saved $750m by slashing its advertising and marketing agencies from 6,000 to 2,500, and aims to halve that number again.

Many large companies, including US food producers Kellogg and Campbell Soup, have set up venture capital arms to jump on promising start-ups. General Mills, producer of Cheerios cereal, used its 301 Inc subsidiary to invest in Rhythm Superfoods which makes broccoli snacks and kale crisps.

Unilever has spent more than €9bn on about 20 acquisitions since 2015, mostly small companies, including Dollar Shave Club, Pukka organic teas, and Seventh Generation eco-friendly laundry products. These “speedboats”, as Mr Polman calls them, are one way to capture fast-moving trends and learn from those entrepreneur founders who agree to stay on board.

With vegetarianism on the rise, US meat processor Tyson Foods is hedging its bets about future diets. It has invested in Beyond Meat, a plant-based start-up that makes meatless burgers.

And companies are trying to appeal to a younger generation with new products. Unilever had not launched a new product for two decades until last year when it came out with half a dozen, including Love, Beauty and Planet shampoos and shower gels.

Big brand dilemma: will anything really help?

The question is whether these strategies will work.

Mr Lemann said at the Milken conference that changes in developed markets such as the US are not happening so quickly elsewhere. He was optimistic that once similar trends emerged in other countries, consumer companies would be ready. AB InBev had been taken by surprise by the rise of craft beer, he admitted. “We reacted, we bought 20 craft companies. In international markets, if craft appears in Argentina or Brazil, we’ll buy it right away.” The 78-year-old is certainly not going to give up. “I’m not going to lie down and go away,” he said.

Nestlé’s Mr Schneider does not believe that big companies need to downsize. “Can we really compete with three guys in a garage? No, we cannot and, honestly, we shouldn’t try. Sometimes it’s good to have entrepreneurs test out trends first, then being a fast follower is good enough.”

One industry veteran thinks, however, that big brands have probably lost a certain type of millennial consumer. Elio Leoni-Sceti held senior roles at Reckitt Benckiser, the Dettol disinfectant to Mucinex cold remedies group, and was head of frozen foods group Iglo. He co-founded The Craftory, an investment group launched last month to help challenger companies grow.

He believes that consumers looking for good-value “average quality” would continue to buy big brand names. But, “there is a growing and significant percentage of consumers, call it around one-third in the developed world, which is not looking for this kind of brand. A lot of these [big] brands are trying to reinvent themselves for this kind of demanding consumer but many of them fail. When a brand tries to dress up differently, consumers disassociate and don’t engage.”

Others argue that big brands should be able to regain their poise. “We’ve heard the cry that ‘brands are dead’ every year without fail for the past 15 years,” says Richard Taylor, analyst at Morgan Stanley. “The 200-year history of global fast-moving goods companies strongly suggests that brands will endure.”

Martin Deboo, analyst at Jefferies, agrees. “Millennials have certainly been putting the fear of god into the staid US food industry,” he says, but “fragmentation fears are overdone” and the best players will be able to adapt.

The Millennial Moment

Articles in this series examine millennials’ dramatic impact on the world’s economy.

Part one

Introduction, and millennials in charts

Part two

Disruption: The ‘millennial’ World Cup

Part three

Authenticity: The new consumers

Part four

Community: Millennial cities

Part five

Thrift: Saving not wasting

Part six

Experiences: The ‘feeling’ economy

Part seven

Immediacy: Instant money

Part eight

The future of millennial living

Explore the series here.

As for Mr Branson, with his “scary, crazy dream of wanting to change the way the world drinks”, he has no complaints about Diageo. He is grateful for their support while being left to get on with the business.

But he knows he does not want to run Seedlip forever. “I’m good at starting things but I’m not really a commercial mastermind that’s going to take something from 100,000 to 200m. I’m not good at making things big — I’m not excited about that at all.”

The FT is looking to hear from young readers: how do you spend your money, and how financially stable do you feel? Contribute to our reporting here.

Are you interested in news and analysis about the markets? Sign up to the FT Markets WhatsApp group. Whether you are a subscriber or not, the stories will always be free (outside of the FT’s subscription paywall).

Comments