Saudi Arabia plans $27bn in bond issues

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Saudi Arabia is returning to the bond market with a plan to raise $27bn by the end of the year, in the starkest sign yet of the strain lower oil prices are putting on the finances of the world’s largest oil exporter.

Bankers say the kingdom’s central bank has been sounding out demand for an issuance of about SR20bn ($5.3bn) a month in bonds — in tranches of five, seven and 10 years — for the rest of the year.

Fahad al-Mubarak, the governor of the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, said in July that Riyadh had already issued its first $4bn in local bonds, the first sovereign issuance since 2007.

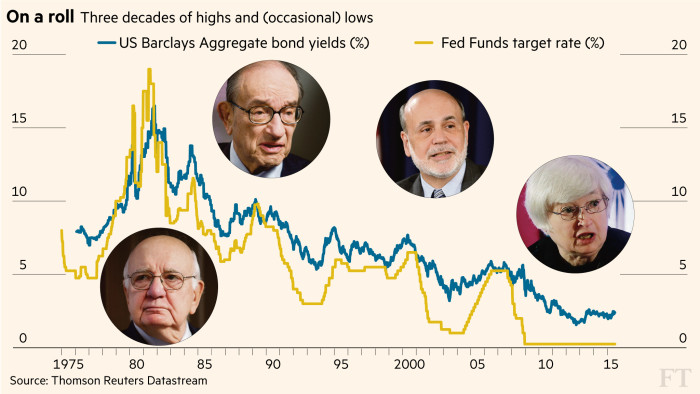

Debt markets: After the binge

Low interest rates sparked record bond issuance but with rates set to rise the market is anxious

Continue reading

But the latest plans represent a major expansion of that programme, which bankers believe could even extend into 2016, given the outlook for the oil price.

Saudi Arabia’s resort to further domestic borrowing highlights the challenges facing the region’s largest economy amid one of the steepest falls in the oil price in recent decades. Brent, the international benchmark, has dropped from $115 a barrel in June last year to about $50 this week.

Oil’s decline accelerated in November when Opec, the producers’ cartel, decided not to cut output, a major departure from its traditional policy of trimming production to prop up prices. Saudi Arabia said it was an attempt to defend market share against rivals such as the US shale industry.

But the decision to ride out a sustained period of lower prices has put a huge strain on the finances of major oil exporters, including Saudi Arabia which requires an oil price of $105 a barrel to balance its budget.

The kingdom has drained $65bn of its fiscal reserves to maintain government spending since the oil price plunge began. Sama currently has $672bn in foreign reserves, down from their peak of $737bn in August 2014.

The plan to resort to capital markets, if confirmed, demonstrates the priority Riyadh is placing on maintaining government spending, despite the pressure cheap oil is putting on its budget.

The monthly bond issuance plan would only cover part of the deficit, which economists estimate will reach SR400bn this year amid falling revenues and continuing high expenditure on big infrastructure projects, public sector wages and the continuing war in Yemen.

“This is all about rebalancing away from the reserves — using some debt to help make up the budget deficit,” said one banker aware of the plan.

The bond plan has echoes of the 1990s, when Riyadh issued local banking debt via Saudi government development bonds.

At one point at the end of the 1990s, Saudi debt reached 100 per cent of gross domestic product. It was only when oil prices began their sharp ascent in the early 2000s that Saudi debt levels began to come down.

Podcast

Saudi Arabia feels impact of low oil prices

The kingdom is considering borrowing money on the local market in order to fund a growing budget deficit

“The government needs to be clear about how much it borrows and from where,” said John Sfakianakis, regional managing director for Ashmore Group, who believes Sama should tap international debt markets to prevent private sector loan growth slowing too sharply. “This is a significant move for a significant global economy, so we need transparency.”

Sama, which has yet to announce the plans publicly, was unavailable for comment.

Ali al-Naimi, the kingdom’s oil minister, flagged in an interview last December that Saudi Arabia could tap the debt market. “A deficit will occur,” he told energy publication MEES. “But . . . we have no debt. We can go to the banks. They are full. We can go and borrow money and keep our reserves. Or we can use some of our reserves.”

Bankers agree that highly liquid local banks are likely to snap up any domestic bond issues this year.

But a resumption of domestic borrowing will also raise concerns that the government is avoiding painful economic reforms, such as ending subsidies and shepherding workers into the private sector and away from government jobs.

Comments