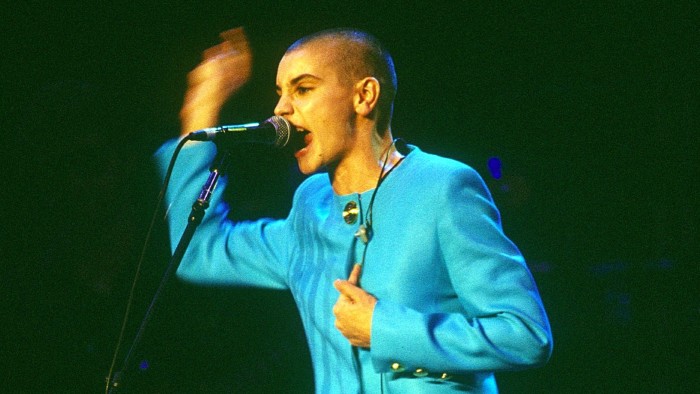

War — when Sinéad O’Connor battled a hostile crowd with Bob Marley’s song

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Midway through a concert in 1992 — to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Bob Dylan’s first recording — Sinead O’Connor took centre stage, intending to sing a sweetly ingenuous version of “I Believe In You”. Watching what happened next is, even now, heartbreaking. O’Connor is smiling at Kris Kristofferson’s introduction, which has praised her “courage and integrity”. But Madison Square Garden is full of shouting, and after a moment it becomes clear that most — not all, but most — of the 20,000-strong crowd are booing her.

The crowd’s anger stems from O’Connor’s appearance two weeks before on Saturday Night Live, where she has concluded her performance by tearing up a picture of Pope John Paul II. (Ripping apart pictures is practically an Irish musical tradition: Bob Geldof famously did this to John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John when The Boomtown Rats displaced them from the top of the charts.) O’Connor’s action was a protest, 18 years before Pope Benedict acknowledged the problem, against child abuse in the Catholic Church. Whatever sort of Dylan fans are in the Garden tonight, their favourite lyric is clearly not “Don’t follow leaders”: they will not tolerate iconoclasm, or at least not from a 25-year-old Irish woman. The boos grow louder and louder.

Abruptly, O’Connor stops smiling. She stands stock still, barely blinking. The guitarist ventures an opening phrase and she cuts him dead with a wave of her arms. Kristofferson whispers in her ear; lip-reading, you sense he is telling her not to let the audience get her down. “I’m not down,” she replies. The booing has lasted more than two minutes now, an eternity in stage time. Booker T Jones tentatively vamps on piano and O’Connor stops him by drawing her hand across her throat. “Turn this up,” she shouts into the microphone, and then she starts half to sing, half shout: “Until the philosophy which holds one race superior” — she is pulling out her in-ear monitors even as she sings, now valiantly out of tune — “and another inferior, is finally, and permanently, discredited, and abandoned, everywhere is war . . . ”

O’Connor has switched Bobs, from Dylan to Marley.

But these words originated in a speech given a few blocks away from Madison Square Garden, at the United Nations General Assembly, in 1963. The speaker was the emperor Haile Selassie, who had ruled Ethiopia since 1930 (apart from a period of exile during the Italian invasion) and had just founded the Organisation of African Unity.

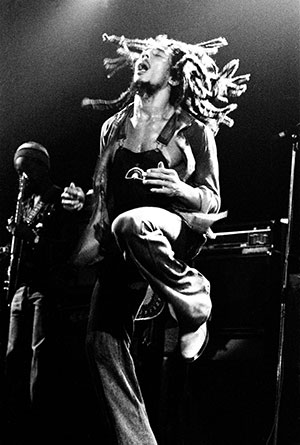

The emperor was worshipped as God by Rastafarians — a belief he did nothing to dispel when he visited Jamaica in 1966. Ten years later the most famous Rastafarian of them all, Bob Marley, set his speech to music, and this became the song “War”, the highlight of the album Rastaman Vibration. Marley’s version, recorded in the febrile atmosphere recreated in Marlon James’s book A Brief History of Seven Killings , sings the words more or less straight, over a steady reggae vamp from Aston “Family Man” Barrett, his brother Carlton, and the other Wailers. Roots reggae traditionally has short, punchy refrains (“Do you remember the days of slavery?”), but this song draws its mounting tension from Selassie’s extended rhetorical complex sentences, release coming only with the refrain of “war”. Later, Marley would use the same rolling cadences for his own “Redemption Song”.

The Jamaican tradition of “versioning”, adding new vocal tracks over the rhythmic chassis of an old hit, went to work on “War”. In 1996 French musician Bruno Blum convened the surviving Wailers to record a backing track over which was laid a recording of Haile Selassie himself. The subsequent album includes a ten-and-a-half minute recording by the emperor of the whole speech, in Amharic, again with reggae backing.

Back in the Garden in 1992, O’Connor, too, is versioning, tweaking the lyrics to drive her point home. “Until the ignoble and unhappy regime which holds all others through child abuse — child abuse — [in] subhuman bondage has been toppled . . . everywhere is war!” She finishes, looks the crowd in the eye, and stalks offstage. The most Dylanesque moment of the night is not even Dylan.

Listen to the podcast

More in the series, and podcasts with clips of the songs, at ft.com/life-of-a-song

Photograph: Getty/Gijsbert Hanekroot

Comments