Markets: Into uncharted waters

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

After a week in which global markets experienced the most severe volatility in more than two years, a phenomenon that investors have been trying hard to ignore came into sharp focus. Even after a bout of frantic selling, nothing looked cheap – bonds and stocks were still historically expensive. But there were few other safe places to park their money, with cash yielding virtually nothing.

Investors who have enjoyed impressive returns in recent years are confronting a difficult new period. All year, the US Federal Reserve has been winding down the loose monetary policies that helped fuel the market rallies. As the process nears its end, volatility that had been restrained for several years has returned with a vengeance. And there are few compelling narratives that investors can use to guide them as they try to decide where to put their money.

Surveying this landscape, it appears they are choosing the least bad option and pumping money back into expensive stocks, as they did yesterday. Some investors worry that this is could soon become a problem.

Jeremy Grantham, founder of GMO, the asset manager in Boston, has predicted that rising dealmaking would “push the market up to true bubble levels, where it will once again become very dangerous indeed”. Yet in its latest long-term forecast, released this week, GMO says that returns from cash, US bonds and US stocks during the next seven years will be lower than inflation.

Bearish long-term forecasts are well founded. With yields so low, government bonds are very unattractive. Long-term valuation measures show that US stocks are badly overpriced, even if they are not in a bubble.

By one widely used metric, prices of stocks in the S&P 500 are only slightly below their peak in 2007 before the financial crisis – and higher than the peak in 1966 before the long bear market of the 1970s.

Normally a dose of market volatility and a purgative sell-off will ease such problems and create some bargains. But this sell-off has yet to run its course. To understand why, look at the drivers of the return to volatility.

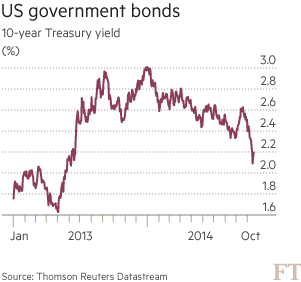

Pivotal was the US Treasury market, where an epic move by hedge funds into bonds twice brought the 10-year yield, regarded as the risk-free rate for many transactions, below 2 per cent.

This made many market experts look bad. As the year began, the Federal Reserve had announced the beginning of its programme to taper off its purchases of government and mortgage-backed bonds, known as quantitative easing. These purchases were intended to stimulate the US economy by keeping bond yields low. Removing the stimulus, as the Fed did steadily throughout the year, was expected to raise yields.

No fewer than 97 per cent of economists surveyed by Bloomberg in January expected interest rates as set by the bond market to rise over the next six months. By April, this figure rose to 100 per cent. Instead, the yields fell steadily all year – until this week, when the fall turned into a rout. Many investors were caught betting the wrong way and had to abandon bets that had already lost them a lot of money.

Even if their bet turned out to be wrong, it was a reasonable one. Treasury prices have been rising steadily for more than 30 years – ever since Paul Volcker’s Federal Reserve convinced investors that it was committed to controlling inflation. Any US recovery ought to push yields back upwards. Arithmetic and logic therefore suggested that their price should fall.

But demand for bonds remains strong, for two reasons. The first is macroeconomic. Recent months have seen growing evidence of deflationary pressure, particularly from the eurozone. This attracts money to the US, raising the value of the dollar against other currencies, which helps to weaken the price of commodities, particularly oil. Crude oil has fallen almost 30 per cent since June in spite of events in Iraq. Lower oil prices reduce inflation.

There are good arguments that the US economy is not yet in any danger of deflation. This week brought the good news that fewer Americans were signing on as jobless than in any month since early 2000. But at the margin, the risks of deflation have increased. Bonds become far more attractive when there is little or no inflation. The second factor supporting bonds is technical. Pension funds are more conservative post-crisis, placing an emphasis on being able to guarantee meeting their liabilities, rather than attempting to maximise their performance. This means buying bonds.

Jim Sullivan, head of Prudential Fixed Income, which manages more than $400bn in bond funds, reports that its assets under management have grown by about 20 per cent a year since the financial crisis, buoyed by pension fund managers’ systematic de-risking. He predicts that 10-year yields will stay well below 4 per cent for years to come.

So even though Treasuries are obviously expensive, it is dangerous to bet against them.

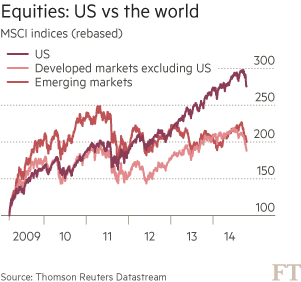

What about stocks? The main indices in western Europe and Japan have suffered falls of more than 10 per cent in recent months. In the eurozone, weak German economic data and rising yields on Greek debt have rekindled fears of a sovereign debt crisis. Emerging market equities look relatively cheap but only because their risks seem high. The Chinese economy, which is slowing, and where fears of a credit bubble are growing, provokes great uncertainty, while falling commodity prices have put pressure on raw materials exporters such as Russia and Brazil.

But the US market stands uncorrected. Even at its lowest point this week, the S&P 500 never fell 10 per cent from the high it set last month – the definition of a market correction.

There is no evidence of panic selling – always necessary before a market bottom can be established – while US strategists and investors seem overwhelmingly confident that it is time to buy more. BlackRock, the world’s biggest fund manager by assets, reported that its equity products registered net inflows in the week to Wednesday.

“The low level of selling is pretty shocking given the magnitude of the recent losses,” said David Santschi of TrimTabs, who suggested that investors had been “extraordinarily complacent”.

What will move markets from here? In the short run, hints by James Bullard, a Fed governor, of a postponement of the end of QE bond purchases, expected this month, seems to have driven a rebound late in the week.

But if an economic “hard landing” in China or a resumed crisis in the eurozone knock the US economy off course, the question would be whether the Fed, after six years of crisis-fighting, still had any tools left to stimulate the economy.

David Bowers of Absolute Strategy Research in London says investors have a lot riding on the notion that the US economy will keep improving even as the rest of the world lapses into deflation. US stocks have outperformed the rest of the world since the post-crisis rally in 2009, and that outperformance has become exponential during the past few months. This is hard to sustain.

If the global economy remains slow – as recent forecasts by the IMF and others suggest – but not slow enough to pull the US into outright recession, then the logic of the last few years will continue to apply. Even though bonds and stocks are historically expensive, investors will have little choice but to buy.

Big institutions are desperate for a way out of the problem. Some are flocking to so-called real assets – a process that Bernie MacNamara of JPMorgan Asset Management has termed “the realisation”. “With public equity markets highly correlated to each other and most fixed-income yields continuing to disappoint, many institutional investors may have come to the realisation that the public markets alone are unlikely to get them to their long-term investment goals,” he says.

Pension funds are investing in real estate and infrastructure. US foundations are also buying up wind farms and farmland, on the theory that its supply is fixed and can only grow more valuable as the population grows.

As for GMO, which now publishes a “primer on farmland investing”, the one asset class that it predicts will return more than 5 per cent annually over the next seven years is timber. The appeal is that timber is not strongly correlated with economic activity and the market for it is reasonably predictable.

There are disadvantages, though. This is a specialised asset class if ever there was one. And, like the other real assets, it is very hard for anyone but the very rich to enter. GMO’s own forestry fund is not open to new investors.

Sadly for Main Street investors, the opportunity to buy an asset that is reasonably priced seems to be restricted to the very wealthy. But if the market confusion makes it hard to see the wood for the trees, there will always be timber.

Comments