Warren Buffett: Know when to hold ’em

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Investors awaiting Warren Buffett’s annual letter will get three for the price of one this year. The founder of Berkshire Hathaway is planning a special “golden anniversary” publication, marking 50 years since he took a controlling stake in the company.

Mr Buffett and his business partner, Charlie Munger, are independently writing their views of Berkshire’s extraordinary journey during the past five decades — and what they expect for the next five. Neither is changing a word of the other’s commentary. Readers will be able to compare the two sets of reflections and predictions, in addition to the regular annual letter.

By writing about the next 50 years, the two men, who have a combined age of 175, will be attempting to shape the future of Berkshire — and their legacy — amid an intensifying debate about what this unusual company will look like when they are gone.

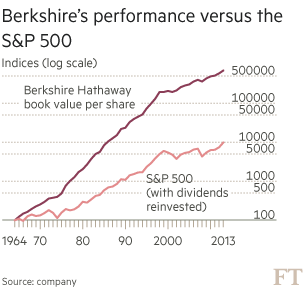

They took an ailing New England textile business and turned it into one of the most successful investment vehicles in history, through a combination of acquisitions in insurance and other industries and a portfolio of equity investments in American icons such as Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and American Express. Over the past generation, as shareholders at other companies have demanded a focus on a core business, Berkshire has only diversified more.

Now, with the addition of US power companies, one of North America’s largest railways and a 50 per cent stake in Heinz, it is probably the world’s most diverse conglomerate; it is certainly the largest. With a market value of $358bn, it is bigger than General Electric.

As Mr Buffett, 84, the company’s chairman, chief executive and chief investment officer, has aged, the debate about whether the ragbag entity should be split apart after his retirement has only got louder. But the debate may be shifting. While he and Mr Munger, the 91-year-old vice-chairman, insist that they have built an enduring company with a culture all its own, investors, analysts and long-time Berkshire watchers are focusing on more nuanced questions of management structure.

“The most important thing to Warren Buffett is, how can he position Berkshire for the future so that it continues to generate increased value for shareholders,” says Jay Gelb, an analyst who covers the company for Barclays and who is invited each year to pose questions to Mr Buffett at Berkshire’s annual meeting. “I think this could be his most important annual letter yet.”

Mr Buffett’s missives, which come out around the end of February and run to 30 pages or so, are packed with nuggets of investment wisdom, expansive pedagogical passages and jokes. The world’s most successful fund managers, private equity bosses and corporate chief executives cite them as influences and read them just as voraciously as any small shareholder or business student.

Yet perhaps the letters’ biggest role is to be the glue that holds Berkshire together, the philosophical foundation of a confounding company.

The forthcoming Buffett and Munger road maps for the next 50 years could act as companion to the “Owner’s Manual” Mr Buffett wrote for Berkshire shareholders in 1996, in which he set out 15 guiding principles. These included a promise to seek solid businesses and to hold them forever, instead of chasing quarterly earnings and churning the portfolio. It also enshrined Berkshire’s management culture, which leaves subsidiary company bosses to run their own show, without interference from the head office in Omaha, which is still staffed by just 25 people.

The annual letters include pointed exhortations against paying dividends or taking on too much debt, all of which will be hard for Mr Buffett’s successors to ignore, and which they can use in answer to outsiders urging change.

“No one who steps into his shoes will have Mr Buffett’s authority or credibility,” says Larry Cunningham, the law professor and author, who has published an annotated anthology of the letters. “To the extent that he can provide texts, rules, principles, it will all be very helpful. It will fortify the successor.”

Such fortification may be necessary in an age where hedge fund activists are gaining traction with their demands that companies spin off divisions, halt investment, add debt to the balance sheet and return cash to share-

holders — actions which are anathema to Mr Buffett. Close followers of the company say talk of breaking up Berkshire will remain just that: talk. In fact, several are betting it will be able to keep bulking up, both under the present management and over the long run under Mr Buffett’s successors.

Under its present structure, Berkshire can invest the cash from its operating businesses and the premiums raised by its insurance companies, giving it a financing advantage over others who must arrange more expensive borrowing to do deals. Mr Gelb estimates Berkshire currently has $25bn in excess cash to spend on acquisitions. Its 2013 deal to buy Heinz in partnership with Brazilian private equity group 3G Capital — which brought in management expertise — will be a template for even bigger purchases, he says.

“He is trying to put all the pieces on the board so that the next CEO does not need make any overly challenging decisions,” Mr Gelb said. “The Buffett estate will still own a substantial proportion of the company, so it is not as if an activist can immediately come in and demand changes. That allows the next CEO some room to manoeuvre without having to worry about what the investor base or analysts like me say.”

Bob Steel, the former Goldman Sachs banker who is now chief executive of boutique investment bank Perella Weinberg, says the rise of hedge fund activism may be a boon for Berkshire, rather than the threat it is sometimes thought of. It may find acquisition targets more receptive to selling out.

“Mr Buffett has built a brand that is seen as a Good Housekeeping seal. He is quite comfortable to let management run businesses and to be supportive, so the brand makes him an attractive person for companies to work with,” says Mr Steel.

“Activism will make the world a different place for lots of companies. If more companies feel uncomfortable making investments, such as spending on research and development, maybe some of those companies will dial 1-800-WARREN and find that to be an interesting alternative.”

If the future of Berkshire is not to be broken up but is in fact to get even bigger and more diverse, then the question switches to whether its current, minimal head office will be able to cope.

Mr Buffett has said the company will split his job between at least three people when he is gone. There will be a chairman, which Mr Buffett hopes will be his son Howard, a chief executive officer and one or more chief investment officers. Academics who have studied Berkshire and other companies think something more radical may be needed.

“A key question is how to impose management change on an underperforming division, when management change becomes necessary,” says Bruce Greenwald, professor of finance at the Heilbrunn Center for Graham and Dodd Investing at Columbia Business School. “People trust Warren Buffett to be an expert in every industry, but they are not going to trust any other single person in that role. His successor would not have the bandwidth or the credibility.”

In his recent book Berkshire Beyond Buffett, which was based on interviews with many of the chief executives of Berkshire’s subsidiary companies, Mr Cunningham floated the idea that the company would need to group the subsidiaries and appoint up to 10 divisional presidents to act as a new layer of management.

This is what happened at Marmon, a mini-conglomerate of manufacturing and services businesses assembled by Jay and Bob Pritzker, which Berkshire acquired in 2007, says Mr Cunningham.

“Both companies were built through acquisitions over decades by iconic figures who knew every bit of history and all of the strengths and weaknesses, and when they left there was no person on the planet who could have that knowledge,” he says. “Mr Buffett’s successor might think ‘I cannot have 80 people reporting to me, but I can divide that by 10’. It seems an inevitable step that someone will have to take.”

Berkshire has already begun grouping results from its subsidiaries under five headings: insurance; railroad; utilities and energy; manufacturing; service and retailing, and finance and financial products.

Meanwhile, Berkshire shares entered the golden anniversary year close to record highs. They jumped by more than 25 per cent in 2014, in part because the company is more heavily oriented to the improving US economy than others of its size, which tend to be multinationals.

With Mr Buffett apparently in fine health, the transition to new management may not be an immediate issue but it tops analysts’ lists of risk factors — and even the world’s largest investors are fascinated by how events will play out.

Interactive

Warren Buffett: A life of dealmaking

Explore Berkshire Hathaway’s purchases since Mr Buffett took the reins in 1964

“I ask myself all the time, when he is not there will Berkshire stock go up or go down,” says David Rubenstein, founder of Carlyle Group, the private equity firm. “And I don’t know. It could go up on the theory that if you broke it up there is more value to it, but it could go down because people think there is nobody who could possibly do what he has done.”

Howard Marks, founder of Oaktree Capital Management, whose own regular investment letters have a wide following, is also watching closely. “They will divvy up the job and, by definition, the person or people managing the money won’t be the greatest investor in history, so it will regress toward the mean,” he predicts. “But hopefully not all the way.”

As Messrs Buffett and Munger put the finishing touches to this year’s letters, they are doing so with eyes as firmly on the future as on the past, with the aim of guiding their successors in managing and investing for the long term.

After Mr Buffett is gone, the letters will remain. And if the message of the letters endures, so too may Berkshire Hathaway.

Additional reporting by Tom Braithwaite

Comments