Literary Life: The Bodleian’s ‘Marks of Genius’ exhibition

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Oxford university’s Bodleian Library received a copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio in 1624, the ghost of its founder probably wriggled in his grave.

Thomas Bodley, the Exeter-born son of a publisher and former Merton fellow, had opened the library in 1602 after returning from a trip abroad to find the university’s reading room in disarray. Passionate about the written word, he made a commitment to “busy my selfe and my friends about gathering in Books”.

But some texts were more equal than others. He once told his librarian Thomas James that “Happely some plays may be worthy of the keeping but hardly one in fortie.” Most likely he would have considered the Folio, which comprises 36 plays and is the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s dramatic works, as an example of what he dismissed as “riffe raffes”.

However, Bodley had been dead 12 years when the Folio took up residence. On arrival, it was sent for binding by local craftsman William Wildgoose and chained up with other folios for readers to peruse. By the end of the century, it was gone, probably sold off once the library had acquired the Third Folio of 1664. It would not reappear for another 250 years, when someone brought it to the Bodleian for an expert opinion. The librarian recognised the Wildgoose binding and — after a desperate campaign to raise money through public subscription — managed to fight off the bid of the American collector Henry Folger and acquire it for £3,000.

In his book Real Presences (1989) George Steiner mused on the way that critical commentaries can act to distance readers from the original text that spawned them. He concluded that “in dispersion, the text is homeland”. The tale of the First Folio — its banishment, return and critical re-evaluation — reminds us that it is our libraries that offer texts a physical refuge from diaspora.

Oxford Literary Festival

David Lodge reflects on the public side of literature

Lorien Kite interviews Kazuo Ishiguro

Oxford Literary Festival highlights

Now the Bodleian will not only house the Folio but display it, too. It is one of 130 objects from the library’s Special Collections that are to be showcased in Marks of Genius, an exhibition that opens on March 21. The show — a smaller version of which was on display last year at the Morgan Library in New York — offers an opportunity to view holdings normally available only to the library’s members, and has been prompted by the recent refurbishment of the building known as the New Bodleian. Built on Oxford’s Broad Street in the 1930s by the architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the New Bodleian served primarily as a bookstore for some 5m books but also included a reading room and offices.

By the turn of the new century, it was clear that change was necessary. The library’s Special Collections required better storage and the building also had to meet the national standard for archive storage. Readers needed more efficient access to materials. Curation and conservation facilities had to be improved.

Given the financial challenges facing Britain’s cultural sector, it was always going to be a struggle to raise funds for a project that would benefit only the privileged few. So the Bodleian’s custodians submitted a plan that would not only renew facilities but also open the Special Collections to a wider public through the construction of new galleries that would host both permanent and temporary exhibitions. They were rewarded with a £25m donation from the Garfield Weston foundation, which in return will see the New Bodleian renamed the Weston Library.

A further £5m was forthcoming from Blackwell’s bookshop, also on Broad Street, and whose osmotic relationship with the library goes back to the shop’s birth in 1879.

Opening in the new gallery, now christened the Blackwell Hall, Marks of Genius might sound like an excuse for a line-up of the Bodleian’s “greatest hits”. Yet a valiant effort has been made to tie the works on show to that protean notion of excellence.

In a fascinating catalogue text, curator Stephen Hebron, traces genius back to its Latin root gignere, which literally means to beget, a reflection of the ancient Roman belief that man was born with his own genius. This guardian spirit, who was not always benign, was similar to the daemon Plato ascribes to Socrates and about which the latter grumbled because it forbade him to do all manner of things yet never suggested any alternatives.

Writing in the fifth century, St Augustine — whose City of God is present in an edition printed in 16th-century Switzerland with a frontispiece bearing metal-cut engravings by Hans Holbein the Younger — believed that genius resided both in God but also in man’s “rational soul”. In the Divine Comedy, showcased through a 14th-century Neapolitan manuscript on parchment, Dante invokes his star sign Gemini as the source of his ingegno. In the acerbic cosmos of 18th-century cartoonists, images of the Magna Carta — a 13th-century copy on parchment is surely one of the show’s highlights — symbolise the “genius” of the nation.

Engaging explicitly with the concept of genius one way or another, most of the aforementioned treasures reside in the show’s opening section “What is Genius?” After that, astute groupings include “Written in their own Hands”, which scoops up original manuscripts by the likes of Maimonides, Jane Austen and Kafka. The latter’s diary includes his conviction that writing should be a bone-stiffening nocturnal marathon: “Only in this way can writing be done . . . only with such coherence, with such a complete opening out of the body and the soul.”

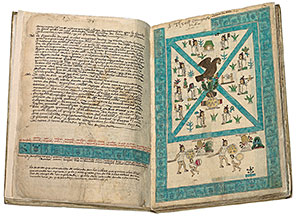

Some of the richest pieces are filed as “The Child of Patronage”. In other words, they were supported or commissioned by powerful third parties. Had Emperor Charles V not thought it worth demanding that his Mexican viceroy Antonio de Mendoza construct an account of the Aztec civilisation, we would not have the Codex Mendoza: a once-in-an-epoch hybrid of indigenous pictograms with a Spanish translation.

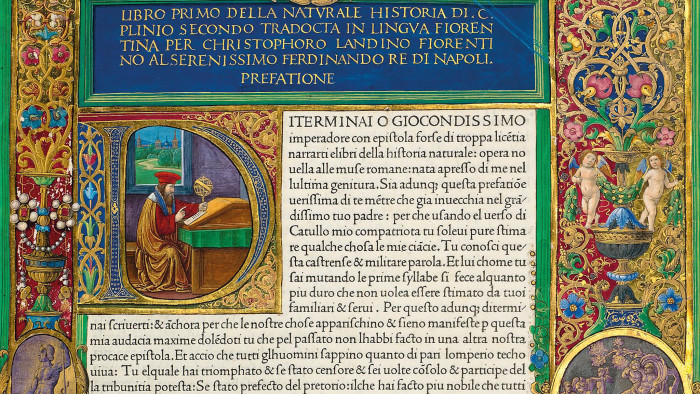

When the Strozzi clan wanted to play one-upmanship with the Medicis, they sponsored the first copy of Pliny’s Natural History in Italian. It was printed in Venice — whose Renaissance presses are responsible for a number of texts in this show — but Filippo Strozzi needed special treatment. He commissioned the Florentine miniaturists and brothers Giovanni and Monte di Miniato to hand-paint exquisite borders and initials on his copy. That beauty is the edition that belongs to the Bodleian. Like much else in this show, it is a triumphant testament to Bodley’s own genius for “gathering”.

Of course, the university’s alumni are a prime source of the rarities here. When I paid a visit to Chris Fletcher, the Bodleian’s head of Special Collections, he showed me an edition of Horace’s Odes that had been written out by William Morris, with the collaboration of Charles Fairfax Murray and Edward Burne-Jones, in the style of a medieval illuminated manuscript. Morris was a member of the Bodleian — he took a peek at their lovely Venetian Pliny when he was seeking a new typeface for his Kelmscott Press — so for his daughter May it was the natural home for his legacy.

The journeys of more ancient residents are often labyrinthine. For example, the 13th-century Ashmole Bestiary once belonged in the cabinet of curiosities of the erudite 17th-century gardener Sir John Tradescant. It was left by his son to Elias Ashmole, founder of the Ashmolean museum. Transferred to the Bodleian in 1860, this hand-painted compendium of real and imaginary beasts joyously illuminates corners of the medieval mind where, for example, elephants and unicorns enjoy an equally vivid existence.

When Jorges Luis Borges imagined his all-encompassing Library of Babel, he installed every text from “the archangels’ autobiographies” to “the Gnostic gospel of Basilides [ . . . and] the true story of your death”. Embracing a cornucopia that includes the world as plotted by Ptolemy (his Geographia is present in a 15th-century edition), the planets as mapped by the 12th-century Persian astronomer al-Sufi in his Book of the Constellation of the Fixed Stars, and time as organised by the calendar of a Ming emperor, this exhibition irresistibly evokes Borges’ fantasy book room.

Balancing erudition with clarity, the catalogue is an invaluable guide to some of civilisation’s textual cornerstones. It might even satisfy Borges’ longing for a “catalogue of catalogues”, yet in true Borgesian style it also undermines its own claim to truth. Hebron’s essay quotes Orson Welles, who thought that the 20th century contained only three true geniuses: “Einstein, Picasso and somebody from China we’ve never even heard of.” Perhaps; but if that bright spark from Asia hasn’t found their way into the Bodleian yet, it’s only a matter of time.

‘Marks of Genius’, Bodleian Library, Oxford, March 21 to September 20, genius.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

Photographs: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Comments