Goldman Sachs: A play for the 99%

Simply sign up to the US & Canadian companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In April this year Goldman Sachs did something it had never done before. For almost 150 years, it had prospered by getting close to people of power and influence: wealthy institutions, multinationals, rich families. Now it was trying to appeal to hoi polloi, offering online savings accounts that can be opened with a deposit of just $1, with interest rates about 100 times better than those at big US retail banks like Wells Fargo or Bank of America.

But the launch of GS Bank, propelled by the acquisition of a $16.5bn book of deposits from GE Capital, was not exactly glitch-free. People were baffled by an automated menu system that failed to recognise simple instructions, says Rob Berger, founder of Doughroller.net, a personal finance site. Some customers reported long delays in opening an account; others complained that they could not get on to the platform via an iPad or a Chromebook.

Even now, GS Bank’s call centre in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, is not open 24 hours a day, unlike other providers of online savings accounts such as Capital One, American Express or Discover.

“Because it was Goldman everyone expected the white glove service,” says the head of a cash management firm. “It was not the white glove service.”

Goldman is moving into Main Street for a simple reason: life on Wall Street has become much tougher since the global financial crisis. Once-powerful business lines such as fixed-income sales and trading have been struggling with tighter regulation and a shift to electronic platforms, while choppy markets have discouraged clients from putting on big and complex trades that have long been Goldman’s forte.

At the same time, revenues in the bank’s asset management division have been squeezed by a broad shift to passive rather than active investing. Even Goldman’s investing and lending segment, a ragbag of businesses involving the bank placing bets with its own capital, has been hemmed in by new restrictions on proprietary trading.

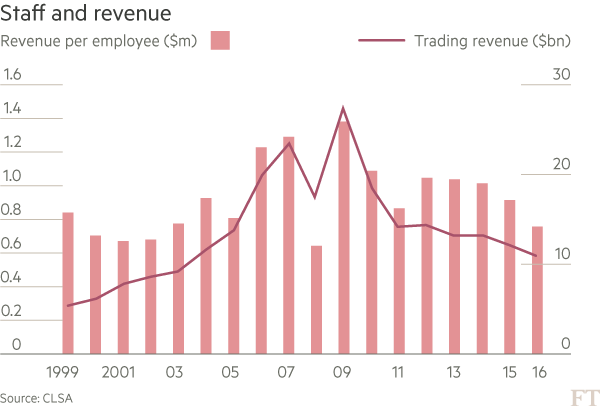

All that has weighed on profits. Goldman’s return on equity — the best and simplest measure of how well it is using shareholders’ money — slipped below 10 per cent last year and is expected to come in at about 8 per cent in 2016. That would make two years of annual RoE in single digits — easily the worst run since Goldman went public in 1999.

Post-crisis struggle

Goldman’s returns have been better than peers such as Citigroup, BofA and Morgan Stanley, which have undergone more radical surgery, selling assets worth tens of billions of dollars while shutting entire business units. But some investors still wonder why Goldman, a bank that has always taken pride in the strategic advice it provides to clients, seems to be finding it hard to adapt to the post-crisis world. For the past four quarters it has lost its crown as Wall Street’s most profitable listed bank — a title that now belongs to JPMorgan Chase.

“You’d have thought that Goldman, the great restructurers, would have been able to re-engineer the business, but they haven’t,” says Jeff Morris, head of US equities at Standard Life Investments in Boston. “If Goldman can’t change their business to achieve better returns, it really speaks to how tough the regulatory environment is.”

Executives at Goldman bridle at the suggestion the bank has stood still while the world changed around it. They point out that it has kept annual revenues more or less steady at about $34bn since 2012, despite cutting risk-weighted assets by about one-fifth in that time, on estimates from CLSA, the brokerage.

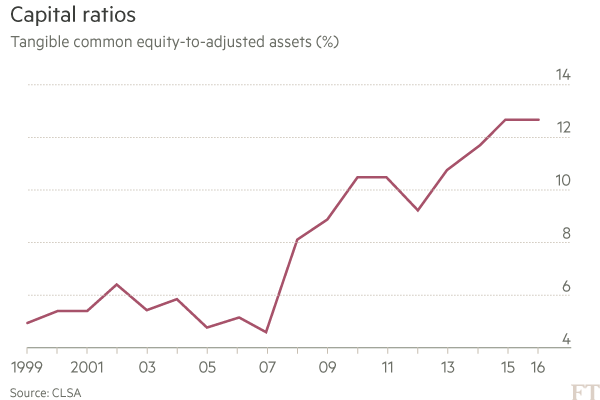

They also note that the bank has responded to regulatory demands by roughly doubling its equity capital since the crisis, which compresses returns to shareholders.

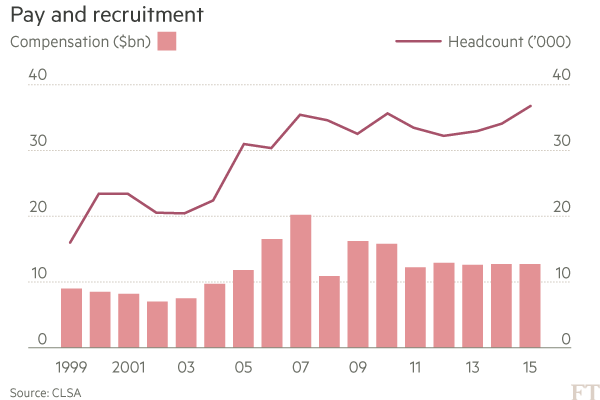

Pay — often a flashpoint — has come down a lot too, reflecting smaller bonuses as well as the different business mix. In the second quarter this year, Goldman’s accrual for compensation and benefits came to $95,718 per employee, less than half the figure of $211,968 of 10 years ago.

At Goldman’s annual shareholder meeting in Jersey City in May, Lloyd Blankfein, chairman and chief executive, said that if profits had been weak, it was because of heavy exposure to hedge funds, asset managers, banks and brokerages — groups that are inclined to shut up shop in thin, brittle markets. By contrast, universal banks such as JPMorgan Chase and Citi deal with huge multinationals that need steady flows of interest-rate swaps and currency hedges, whatever the weather.

Once investors regain some poise, said Mr Blankfein, Goldman would bounce back too. Higher interest rates, lower energy prices and a stronger economy should help boost the “velocity” of trading. “There are signs on the horizon and indications that we are finally, after a very long time, coming out of that [low volume] environment,” he said.

But the strategy of being the “last man standing” in trading is a risky one, says Mike Mayo, an analyst at CLSA in New York.

He points to there being no guarantee of livelier markets, and increasing capital requirements imposed by regulators. Even if the biggest banks pass the annual stress test, he notes, the Federal Reserve is not letting them return more than 100 per cent of earnings via buybacks and dividends.

In that context, say analysts, Goldman needs new income streams to boost RoE. In the autumn it plans to start putting its new GE connections to work, launching a venture offering loans online to consumers and small businesses. That unit has hired dozens of senior people from companies including Lending Club, Citi, Amex and Barclaycard.

More retail banking products could follow — such as car loans, mortgages or a “robo” wealth management platform. In March Goldman took a step in that direction by buying Honest Dollar, an Austin-based start-up that helps freelancers and small businesses set up retirement savings programmes online.

It was a deal that gave the buttoned-up bank a new managing director in Texas: William Hurley, a former IBM and Apple executive — and ex-bassist in a funk band — who goes by the name of “Whurley.”

“In the new regulatory world, any profitable business that you can get in to that fits, you have to look at,” says Jeffrey Harte, an analyst at Sandler O’Neill in New York.

Retail push

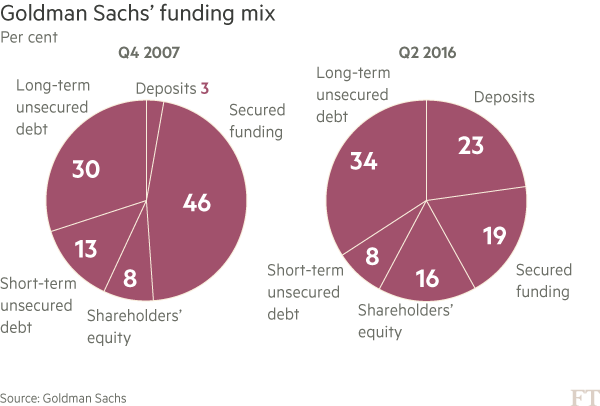

Before the financial crisis, Goldman did not even have a federally insured bank but it was forced to open one in 2008 as a condition of receiving bailout funds. Since then, it has gone after wholesale deposits aggressively, seeking to cut its dependence on the short-term debt markets that froze during the crisis.

Deposits now account for 23 per cent of the bank’s funding mix, up from 3 per cent at the end of 2007. The bank is now much less likely to suffer the kind of liquidity crunch that saw off Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers — and almost did for Goldman itself.

The new mix helps profits, too. Even though Goldman is paying its GS Bank depositors a near market-leading interest rate of 1.05 per cent a year on online savings accounts, for example, that is still much less than the cost to Goldman of issuing long-term bonds.

But getting closer to retail depositors via the GE deal is more than a matter of cheap, sticky funding. It also opens Goldman up to a new class of customer: the 99 per cent.

Until the price of entry dropped to a dollar, people used to need at least $10m in net assets before they could become a Goldman Sachs account-holder. Now, if anyone wants to put down more than $250,000 — the standard government insurance coverage limit — they have to go elsewhere. (GE had set the bar much higher, at $1m.)

GS Bank’s 160,000 or so depositors should be a useful support for the new lending venture, which represents a direct strike against peer-to-peer platforms, which match needy borrowers with investors hungry for yield. In a research note last year, Goldman analysts said $10.9bn of annual profit generated by traditional bricks-and-mortar lenders was at risk of being lost to more nimble upstarts. Of that, the largest chunk — $4.6bn — was from unsecured personal loans, with another $1.8bn from small business loans.

A successful launch of a Lending Club-like business would be a feather in the cap of Stephen Scherr, a former head of the financing group who was named chief strategy officer in June 2014. This summer he was given the extra title of chief executive of GS Bank USA, the banking arm, suggesting that he has joined a front rank of candidates to lead the whole bank one day.

Institutional makeover

Recasting Goldman as the friend of the consumer and small business will not be easy. For many people across the US, the brand is associated more readily for its legal and political scrapes after the financial crisis than its philanthropic programmes such as “10,000 women” or “10,000 small businesses.” Within the past year, the bank has taken hits for its connections to 1MDB, the Malaysian sovereign wealth fund at the centre of a sprawling corruption probe. This week, Edwin Chin, a former head trader, was barred from the industry by the Securities and Exchange Commission and ordered to pay $400,000 to settle accusations that he repeatedly mischarged customers.

Yet to others the Goldman name means almost nothing. Brenton Givens, a 44-year-old Avon representative from Hawthorne in Los Angeles, says he knew very little about the bank when it replaced GE but closed his account after a few months, attracted by better offers elsewhere. He now prefers an app called Digit, which sweeps money from cheque to savings accounts without fees.

Former Goldman staffers also wonder whether all the new arrivals at the digital consumer financial services unit — including a former head of marketing at Jockey International, the underwear company — will thrive at the bank, which has previously developed its own leaders.

One former employee notes a more fundamental mismatch: the fact that making money from retail banking depends on churning simple, low-margin transactions at high volumes. That is the opposite of Goldman’s core strategy over its 147 years, which has focused on complicated deals for big clients.

Goldman is clearly gunning for growth from GS Bank: vacancy lists on its website show 22 positions available at the unit, more than in securities and investment banking combined. But the “strategic pivot” to traditional banking will make sense only if it leads to better returns, says Mr Mayo.

For now, he says, it is clear only that “Goldman has not evolved as quickly as it should”.

Comments