Australia steeled for China slowdown as iron ore prices fall

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The last time Western Australia was engaged in a dispute with Canberra of this magnitude, it threatened to secede during a financial crisis sparked by the 1930s Depression.

The current friction is linked to China’s slowdown — a sign of how closely Australia’s fortunes are tied to Beijing’s appetite for its commodity exports.

“It’s not secession but it is tension and disengagement,” Colin Barnett, Western Australia’s premier, said this week when Canberra and other states rejected a request to help plug a widening hole in the state budget caused by plunging iron ore prices.

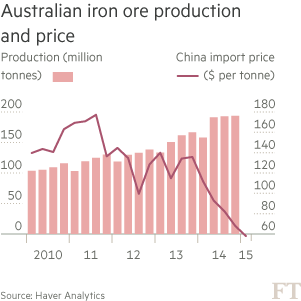

Western Australia is a mining state that enjoyed a decade-long boom selling iron ore — a key ingredient in steel — to China. Known by some as “China’s quarry”, the state hosts BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals Group, which have spent billions of dollars building mines, railways and ports to almost double iron ore production to 717m tonnes over the past five years.

But just as global supply hits record levels, China’s economy is slowing and its desire for the reddish-brown ore may have plateaued. Since peaking at US$190 in 2011, iron ore prices have slid more than 70 per cent to about US$50 a tonne. This is denting tax revenues, forcing smaller mining companies to close and lay off thousands of employees.

“Western Australia was the big beneficiary of the China boom,” says Chris Richardson, economist at Deloitte Access Economics. “But it is suffering now as the mine construction phase ends and commodity prices fall amid a surge in iron ore supply and faltering demand.”

In 2013 the state lost its triple-A credit rating. On Tuesday, Standard & Poor’s warned it may face a further downgrade because of its budget problems.

Western Australia says that if iron ore prices stay at US$50 per tonne it would wipe out A$4bn (US$3bn) in projected royalty revenues in 2015-16 — 12 per cent of the state budget.

Unemployment in the state, although still modest at 5.8 per cent, has risen from 3.8 per cent when iron ore prices peaked. House prices have started to fall in the state capital Perth, while they continue to grow in Sydney and Melbourne.

Mr Barnett wants other states to give Western Australia a greater share of revenues from a nationwide goods and services tax. But so far Canberra and other states have rejected his pleas. On Friday, state premiers will discuss the dispute.

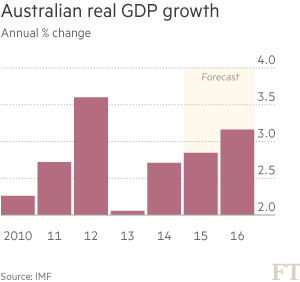

Weak Chinese data are fuelling concerns that Western Australia’s problems could spread across a country that has avoided recession for two decades by riding China’s commodities boom.

Iron ore is Australia’s biggest export, worth A$74bn in 2013-14, and the plunge in prices is beginning to hurt the federal budget. In December, Canberra revised its budget deficit forecast to A$40bn, or 2.5 per cent of gross domestic product in 2014-15, up from a forecast of A$29.8bn made in May, citing the impact of a fall in iron ore prices to US$60 per tonne.

Since then, prices have continued to fall further and this week Joe Hockey, Australia’s treasurer, warned they could fall as low as US$35, costing the exchequer a further A$6.35bn a year in lost revenues.

“If iron ore prices stay at about US$45 and export volumes remain at current levels, then Australia should be OK,” says Warren Hogan, ANZ chief economist. “But it is a finely balanced situation and if we see the iron ore price drop lower and Chinese demand fall it could spell trouble.”

The Liberal-National coalition’s second budget next month will be a critical moment. Last year Mr Hockey flagged deep cuts to spending in an attempt to return the budget to surplus. Many of these reforms remain blocked in the Senate. Similar tough medicine this year could undermine confidence at a time when the Reserve Bank of Australia is trying to encourage business investment to diversify the country’s resource-dependent economy.

“There is a need to get businesses to invest and take advantage of opportunities as China transitions to becoming a consumer-led economy,” says Mr Hogan. “Agriculture, tourism and education are key sectors.”

A weakening Australian dollar and a loosening of visa rules are boosting inbound tourism. In the year to the end of September, 789,000 Chinese tourists visited Australia, up 10 per cent on a year earlier. Chinese tourists are now second in number only to New Zealanders — and they spend the most at A$5.4bn a year.

Whether these alternative industries can cushion Australia from the collapse in commodity prices remains to be seen.

“China won’t be throwing money at Australia any more,” says Deloitte’s Mr Richardson. “And there is a real question mark over whether the country is prepared to undertake the reforms needed to transition its economy.”

Comments