Vienna’s sights set on fostering a generation of tech start-ups

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Vienna’s 13th-century Hofburg palace was once the seat of the Holy Roman Empire. It hosted the premiere of Ludwig van Beethoven’s eighth symphony and provided the setting for US President John Kennedy’s and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s bruising tête-à-tête in 1961 before the Berlin Wall was built.

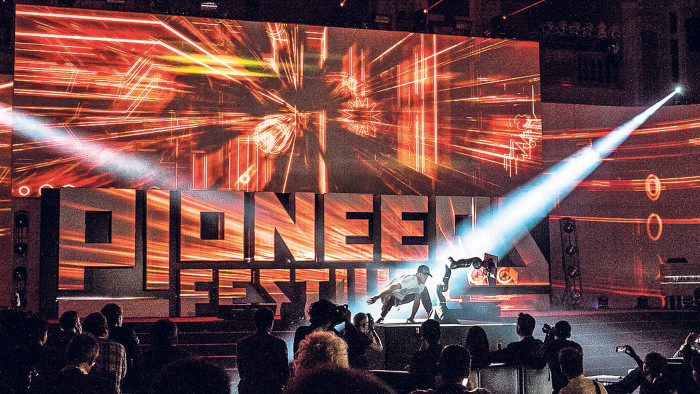

But on a Friday afternoon in May, the biggest draw in its cavernous, marble-lined halls was a virtual reality skydiving simulator opposite a robot dancing to electronic house music.

The takeover of the palace for the annual pioneers festival start-up conference is part of the Austrian capital’s effort to rebrand itself as a centre for innovation and entrepreneurs, amid a fight for talent and capital across central and eastern Europe and further afield.

“Vienna was never famous for having lots of start-ups,” says Peter Bosek, chief retail officer at Erste Group, a bank. But the numbers are definitely increasing. “Of course, compared with London or Berlin we are on a lower level but over the next five years this can be developed in the city,” says Mr Bosek, whose bank has aggressively moved into start-up funding.

Vienna appears to have many of the right attributes to foster a culture of entrepreneurship. The city boasts 190,000 students, roughly 10 per cent of its population, from 20 different universities, many of which are research leaders in their fields.

Traditionally a corporate hub for the region, it has the banks, funds and private capital that are necessary to fuel new businesses. It has a national government and city authorities that are doing all they can to provide an environment for innovative ideas.

But while the Hofburg provides perhaps the most beautiful architectural setting for a start-up conference anywhere, it underlines the difficulty that the historic, old-world city faces in rebranding itself to young entrepreneurs as a location in which to build a futuristic business.

Just a quarter of the start-ups pitching for support and investment are Austrian, underlining the task ahead for the city in competing against other countries and cities with more established start-up hubs.

The global dominance of Silicon Valley aside, other European cities such as London and Berlin have the scale, community and support networks that start-ups need to thrive, creating a virtuous circle and sucking in entrepreneurs from elsewhere.

Other upstarts that offer cheaper living costs and overheads, such as Warsaw and Budapest, are building their own innovation hubs, cutting into the central and eastern European talent pool that Vienna traditionally has drawn from.

“I dare say we are already pushing the right buttons,” says Harald Mahrer, state secretary at Austria’s ministry of science, research and economy.

However, Mr Mahrer, a former entrepreneur who describes himself as Austria’s “chief innovation wizard” adds: “Austria as a business location still lacks various important ingredients that would further foster entrepreneurship and innovation.

“We definitely need to cut red tape, and we need to reduce taxes and social security expenses for start-ups,” he says. “We need to welcome innovators and entrepreneurs, even if their products and services might disrupt established sectors.”

The government has recently passed a law making fundraising through crowdfunding easier and less costly for small companies. It is preparing legislation to give incentives to investment in research and development and provide tax breaks to companies that spend on innovation.

“The politicians are jumping on the train but they don’t fully understand the potential,” said Andreas Tschas, co-founder and chief executive of the pioneers festival, and an expert on Austrian entrepreneurship.

He says that despite the success of the festival, it was a struggle convincing the city that backing it was a good idea. “We are clapping ourselves on the back,” he says. “But Vienna is not really on the [start-up] map . . . Yet.”

That said, a number of Austrian start-ups attracted attention at the festival. Noki, a company that builds electronic devices that allow keyless and remote access to homes, raised a targeted €125,000 in funding in less than nine hours.

Bri.Tech, a company that has designed bone implants that dissolve naturally, removing the need for post-operation surgery, has recently raised €6m and expects to launch on the market within two years.

The city’s authorities are banking on making up for what Vienna lacks in start-up name recognition with generous funding options. In March, Viennese venture fund Speedinvest launched its second fund, which at €60m is the largest raised in Austria.

The government recently passed a law that removes any personal declaration obligations for investments of less than €5,000 and any declaration for companies raising less than €100,000. Full prospectus obligations have been scrapped for any fundraising less than €5m.

If that manages to stimulate Austrian crowdfunding to EU average levels, it should drum up an extra €60m a year for young companies.

That private capital will join already generous public grants and funds made available to entrepreneurs, such as the €68.5m government-backed AWS Founders Fund, and a double equity initiative that means growing companies can get up to €2.5m in a collateral-free loan that is 80 per cent guaranteed by the state.

“The most interesting thing about the city now is a combination of private money and public grants,” says Mr Bosek, who has privately invested in two start-ups himself.

“It would make sense to create a very special environment for start ups here,” he adds

Comments