2012 Bodley Head/FT Essay Prize winner: Getting past Coetzee

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

There is an odd made-for-television documentary from 1997 which shows footage of JM Coetzee conducting a guided tour of Cape Town’s southern suburbs. From the slopes of Table Mountain he points out the hospital where he was born; the suburb of Plumstead where he lived as a young boy; the university campus where he spent much of his academic career. A colleague recalls how Coetzee would not take calls from the Booker prize committee because he was invigilating undergraduate exams: a measure of his professionalism. We visit his Standard Three classroom at Rosebank Primary and the grassy common where he participated in school sports days. He recalls taking gold in the running backwards race of 1948, as if enjoying a wry joke at the expense of anyone who thought that such an exercise might grant some privileged insight into his work.

Ten years ago, I was commissioned by a famous poet-editor to write a profile of Coetzee for a London review. At the time, the offer was a big break, and could have led to great things. I was fresh out of university and the editor was a high-up at Faber and Faber, a talent scout for The New Yorker. But it never got written.

Instead of providing a controlled and judicious survey of the oeuvre, I found myself obsessed by minor details on the outskirts of his work. The grim memoir Youth (2002) had just appeared and I wrote at length about the stockings full of clotting cheese that young “John” hangs up in his kitchen – proof of his extreme thriftiness, in life as in prose. The fish fingers that he fries in olive oil in a London garret, trying to emulate the Mediterranean diet of Ford Madox Ford: these finer points of domestic economy seemed laden with meaning.

And what did the two brooding initials say about his relation to high modernism, I wondered? To the T and S of Eliot, the F and R of Leavis, the D and H of Lawrence? What did the “M” stand for anyway? Was it Maxwell? Like Dylan refusing to sign autographs in the Pennebaker documentary, Coetzee had point-blank refused to answer this question when interviewed. I combed obscure academic journals for more of these duels, rejoicing in how he would not play the celebrity author game. The journalist Rian Malan described how Coetzee wrote each question down on a notepad and methodically analysed the assumptions on which it was based, “a process that offered some sharp insights into my intellectual shortcomings but revealed nothing about Coetzee himself …‘What kind of music do you like?’ I asked, desperately. The pen scratched, the great writer cogitated. ‘Music I have never heard before.’”

The Nobel Prize came and went; the time was ripe for a penetrating summation of (what I should have deemed) “the major phase” – from Waiting for the Barbarians (1980) through to Disgrace (1999) – followed by some measured demurrals regarding the obtrusive postmodernism of “late Coetzee”, from Elizabeth Costello (2003) onwards. But, in fact, all the assignment resulted in was a series of politely worded rejection emails spanning several years. The editor didn’t understand why I had spent quite so long speculating on the anal carbuncle that plagues the murderous frontiersman Jacobus Coetzee in Dusklands (1974). The pages and pages devoted to analysing Coetzee’s early, algorithm-generated poetry were intriguing (he wrote), but perhaps only to the specialist. It was somewhere at the edge of Lake Malawi, during an episode of heatstroke on a long-distance cycling trip (made in honour of the Master of Cape Town) that I finally gave up trying to explain what JM Coetzee meant to me.

This was a novelist who – and I had known this from the opening lines of Waiting for the Barbarians, my first exposure – was simply operating at (the only way I can describe it) a higher pressure than any other from my native land, that country “as irresistible as it is unlovable” – South Africa. But this pressure – the pressure of a toxic history that went far back before 1948, and would last for long after 1994 – was registered in a prose of negative space. While other anti-apartheid writers turned up the heat, Coetzee lowered the temperature until (to borrow from Seamus Heaney on the Polish poets) it began to burn, like the strand of a metal fence gripped in winter.

This was a critic who had said everything about everything, with greater economy and less sentimentality than anyone else (I couldn’t even look at a mountain or a desert or a bird or an animal or a flower without his words getting in the way). Who had been (as Eliot said the artist should be) heterodox when everyone else was orthodox, and orthodox when everyone else was heterodox. Who had, in fact, described the horizon of my thought for my twenties; whose cycling clips I was not even worthy of attaching; whom I desperately wanted to get past, even though the very idea of getting past Coetzee had already been anticipated in his debut effort (damn him!).

…

Ten years later, I find myself a lecturer at the English Department of the University of Cape Town, in the very corridors where Coetzee taught and wrote for so many years. His pigeonhole lingers on, even though he has long since left for Australia, living out his eminent life under the bluegums near Adelaide. There are Coetzee seminars and study groups, Coetzee research clusters and Coetzee collectives. There are posters of him tacked on to doors: Malan’s “crocodile-eyed genius” stares out from New York Review of Books caricatures and the occasional photographic portrait: the small mouth, the handsome, slightly lopsided face.

Droves of students arrive from Wisconsin and Ohio to spend a term abroad, filling the Coetzee sign-up lists, while classes on new directions in post-apartheid poetry or fictions of the Zimbabwean diaspora languish unattended. A steady stream of PhDs and post-docs arrive from York, Auckland, Vienna, Granada and Oslo, ready to present their work in progress.

During a conference last year, I was asked by a visiting academic from Bangalore to take a picture of him standing at the lectern where JM used to teach, as if it were a tourist snap in front of the Little Mermaid. The same lecture theatre – wooden, antique, hidden in the middle of the ivy-clad Arts block – had been used in the filming of Disgrace (2008). Our head of department (my boss) landed a role as an extra, listening to David Lurie (John Malkovich) as he pronounces on Wordsworth’s Prelude (while really ogling his student Melanie). But she (my boss) was caught carrying a copy of the novel in shot – the Vintage edition with the mangy dog on the cover. The director (Australian) deemed her a postmodern agitator and banned her from the set. (Malkovich, though, was most impressed and invited her to brunch with him.)

Since Coetzee lodged his manuscripts in Harvard and now Texas, we have learnt that he wrote his major novels almost entirely in University of Cape Town examination books. They have dull orange covers with instructions printed on them: “Peak caps to be reversed”; “Answer only ONE question per booklet”. Recently I invigilated an exam on his work, striding up the aisles, doling out extra books to diligent students who raised their hands. But, of course, it is the less diligent answers that stay with you. Taking home a stack of scripts to mark, I read a long account of how the protagonist of Life and Times of Michael K (1983) – the silent and harelipped gardener of Coetzee’s greatest, most flawed work – had refused to join the “gorilla” fighters during the civil war, had defended his pumpkin seedlings from the “gorillas”. Magnificent, in its way – a clear First.

Another candidate (who had obviously only ever listened to lectures) wrote a whole essay about “James Coetzee”. James Coetzee – what total and pristine ignorance! How impressive, somehow, that this student had contrived never even to see the Nobel laureate’s name in print. I gave the essay an A+, just for so totally entering into the spirit of the text and its postliterate protagonist. It was 2am and I was going a bit mad. I found myself writing careful and lengthy critiques at the end of each script, marginal comments that nobody would ever read – it seemed appropriately Coetzeean.

In his life of VS Naipaul, Patrick French remarked that it might be “the last literary biography to be written from a complete paper archive”. I sense something similarly historical about Coetzee’s achievement, a power of pre-internet concentration and application that has now been eroded in Version 2.0 people. A mental discipline that can stay trained on things for longer than other minds, without flinching; that can push thoughts, or sentences, one step further than they would normally go.

A quality of, in a word, seriousness. Coetzee says somewhere or other that, for a certain kind of artist, seriousness is an ethical imperative. So why do I find myself wanting to be so unserious in his august presence? To dwell on all those things that cannot be related in the polite literary profile, or the rigorous academic paper. Such as: what does it mean to be obsessed, perhaps unhealthily obsessed, with an author? And: why don’t black South Africans read or talk about Coetzee? And: why am I beginning to think that his work should not be taught at the University of Cape Town – or at least that a 10-year moratorium on Coetzee studies should be declared?

The first answer to the last question is: because Coetzee is too teachable. Or at least a version of Coetzee that has nothing to do with the real Coetzee (I sound like a music snob who discovered a band before it was famous). But seriously: the work lends itself easily, perhaps too easily, to academic explication. The South African poet Basil du Toit wrote that when you bite into a piece of fruit these days, “you find that it has been half-expecting you”. Coetzee’s books have the same GM quality for the literary scholar: they were clearly au fait with various strands of theory during the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, leaving little Hansel and Gretel crumbs behind them, leading critics on like the Pied Piper.

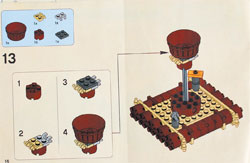

Malan described Coetzee in crocodilian terms; for the poet Breyten Breytenbach he was more like a bird in dense undergrowth: “one hears his allegorical song during certain seasons, but never sees him”. Typically though, the best animal metaphor for describing Coetzee was coined by Coetzee himself: when the crazed spinster Magda of In the Heart of the Country (1977) compares herself to a hermit crab. An apt totem for a writer who inhabits and then abandons the shell of various genres: the explorer’s diary, the story of an African farm, the confession, the campus novel. When teaching Coetzee, the result is a kind of airlessness, or redundancy. He has not only provided the novels, but the secondary readings too. It all comes as a total, all-too-teachable package; a whole literary-critical paraphernalia, which you then assemble together in class like a Lego set.

How canny of him to rewrite Robinson Crusoe like that, with a tongueless Man Friday and a female narrator. Wasn’t a book like Foe (1986) just made to slot into a thousand postcolonial/feminist course outlines on “Rewriting the Canon”, alongside Wide Sargasso Sea and Things Fall Apart? How methodical he had been in his assault on the Nobel – the novels, the serious essays about Kafka, Robert Musil and the Russians, the measured not-quite memoirs – how strategic. Bravo JM!

But this is not really true, or fair, and not really the reason why I am becoming allergic to teaching Him. Some books may smell of the seminar room (particularly the Australian ones), but the oeuvre goes far beyond this. PhD students will no doubt go on following the crumbs, but the theory (if I can switch metaphors) was just the ladder that he climbed up and kicked away from under him; in the same way that his training in mathematics and linguistics (he said) allowed him to think thoughts that he would otherwise not have been able to access.

This is the odd quality about Coetzee’s books. They are at the same time both highly abstract – artificial, allegorical, self-conscious – and shockingly actual. Just when the Marxists were taking aim at him for not being sufficiently engagé (one hot-under-the-collar critic even accusing him of providing little more than “a kind of masturbatory release, in this country, for the Europeanising dreams of an intellectual coterie”), he delivered Age of Iron (1990) – perhaps the most scorching account of South Africa during the late-apartheid states of emergency ever written. And think of that moment when the inscrutable vagrant Vercueil responds to one of the narrator’s cerebral tirades by gobbing a big lump of phlegm – “thick, yellow, streaked with brown from the coffee” – on to the pavement in front of her. For all their intellectualism and abstruse methods, they restore us to the real; we come back to the material world with a jolt.

I see this strange doubleness play out in my desire to make little literary pilgrimages to various sites in Cape Town, even while knowing how ridiculous this is. Coetzee’s entire oeuvre works against the kind of sentimental attachment to place implied by the Dickens walking tour of London, or the Ulysses pub-crawl of Dublin. Nonetheless, I cannot but help recall: the “dim agapanthus walks” where Michael K goes about his gardening in De Waal Park; the gated Greenpoint complexes where Lurie meets the escort Soraya for their weekly appointment – “like the copulation of snakes: lengthy, absorbed, but rather abstract”; the underpass on Buitenkant Street where Mrs Curren collapses in Age of Iron, street children poking sticks into her mouth to check for gold teeth.

Further down Buitenkant is more evidence to suggest that he is widely read beyond the corridors of academe. In the Book Lounge on Roeland Street – Cape Town’s best bookshop – there are no works by Coetzee on the shelves. A little sign tells you to ask at the counter, as if for 19th-century pornography. Coetzee, the staff informed me, is a regularly shoplifted author. This makes him part of an exclusive club that includes William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Gabriel García Márquez …and Paulo Coelho. Those manning flea-market stalls at Greenmarket Square know that these literary goods can be shifted quickly (and I am pretty sure that it is not only the exchange students from Wisconsin who are buying). It is the same kind of back-handed compliment paid to Salman Rushdie when pirate booksellers in Mumbai sent him greetings cards in appreciation for all the money they made from Midnight’s Children.

Perhaps you might say that my reluctance to teach Coetzee is just petulance and possessiveness: resentment at having “my Coetzee” interrupted and interfered with by the world out there (the barbarians). When you feel that a writer is talking just to you, with special insights into your cultural formation, you don’t want to be reminded that thousands of other people (American people, Australian people) feel the same way. But it is more than this: an anxiety that the meanings of these texts – wild, fickle, unmanageable – might solidify, might coagulate for ever.

To lecture on the books, to hear yourself say the same things about them from year to year – it becomes a kind of horror. Do I even want to reread the books of the “major phase”? Tackle Barbarians again? Not really. The meanings of Coetzee to me now reside in all the odd details, offcuts and out-takes that I have tried to enumerate in this essay. So I hope that all this is coming from a deeper, more interesting problem: one that arises when the obsessive-compulsive, often childlike and bizarre relations we have with the one or two authors that really (if I can breathe life into this old cliché) mean the world to us must be disciplined, formalised, professionalised.

And let’s be honest and say how bizarre these relations can be. In Nicholson Baker’s U & I (1991), he at one point takes his chronic eczema as proof of kinship with his hero John Updike, a fellow sufferer. He scratches and scratches in an orgy of identification with his literary subject. In Geoff Dyer’s book about failing to write a book about DH Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage (1997), he burns a copy of the Longman Critical Reader about his hero, given to him by some well-wisher who hears that he is “working on Lawrence”. Over its smoking ashes he asks a question that all literary scholars should put to themselves on a daily basis: “How can you know anything about literature if all you’ve done is read books?”

Let me confess now what went through my mind as I watched that 1997 footage of JM striding over his school sportsfield. He was walking away from the camera and I found myself thinking: right, in a few seconds he is going to have to expose his trousered backside. He will have to reveal those skinny shanks that were mentioned in Youth, those glutei maximi that one of my colleagues (also an avid cyclist) had described seeing so many times sheathed in Lycra, accelerating away in the early morning training run. But no! Coetzee was wearing a low-cut linen jacket that reached down just far enough to cover that sensitive area: his buttocks remained inscrutable. Standard-issue academic gear, of course. But that is the kind of level it gets to, as we review a writer’s life for clues about how to live our own. And that is why I was wearing a low-cut linen jacket while invigilating that exam, handing out the answer booklets, trying to be professional.

Excuse the frenetic tone, but time is running out. Two biographies are forthcoming; one, by the late JC Kannemeyer, has already been published in South Africa and Australia. My Coetzee – already threatened by all the foreign students writing made-to-measure papers about the Ethics of the Other (or the Otherness of the Ethical) – is about to expire, to be dismantled by brute biographical fact. For years I have been deliberately avoiding a physical sighting of him (even while looking for his tracks and traces everywhere I go). I have taken evasive action so as not to meet him in person – I live in fear of (as happened to my boss) bumping into him in a campus car park. But Teju Cole has posted photographs of himself with Coetzee on Facebook – the end of an era. There is less and less space to make the writer (who makes us) what we need him or her to be: mother, father, sibling, mentor, censor, fall-guy, straw-man, drudge, rival …

So permit me one final detour, in which I will try to be serious – or at least serious about my reasons for being unserious. In an early essay on “Idleness in South Africa” (1982), Coetzee examines how early European mariners and colonists at the Cape of Good Hope described the “Hottentots” that they encountered there – the indigenous, nomadic, pastoral bands now called the Khoikhoi. Few peoples were so extensively described, and vilified, during the European voyages of discovery. Their complex click language, their practice of smearing animal fat on their bodies, the different rhythm of their lives – all these were condemned as evidence of idleness, incomprehensibility, barbarity.

In immaculately scholarly fashion, Coetzee shows how the categories and criteria were European constructions, a matrix of cultural codes that worked to justify the colonial argument that only those who worked the land had a right to it. So far, so familiar. But then, crucially, he pushes his thought one step further. Written in hindsight from our all-knowing position, such postcolonial revisitings of the colonial record can mislead us. For “in the very open-mindedness we might like to imagine extending toward the Hottentot from the modern science of Man,” Coetzee writes, “lies the germ of an insidious betrayal of the Hottentot”. Some things should properly remain opaque to us: historically distant, recalcitrant, misunderstood.

I want to wrench this idea totally out of context and apply it to Coetzee’s own work: to sympathise too readily with his writing is to betray it. His writing has bred armies of apologists, explicators, imitators – all of them following his highly serious lead. But the real task is to read and write against him as strongly as possible: flippantly and unseriously. For our visitors from Wisconsin (and many other people abroad, I fear) Coetzee is South African literature. But even though he was so right about the place, he was also so very wrong. What you don’t find in his writing is the beauty of South Africa’s many Englishes, its humour and music, its body language and tawdry brand names, its comedy and its soap operas (political and otherwise). The fact that it is a spoken, rather than a written place; an outward place, and (the odd thing, given its history) a generous one, where things are thrashed out in dialogues with others, rather than selves.

An earlier, Norwegian version of this essay appeared in the literary journal Bokvennen

Comments